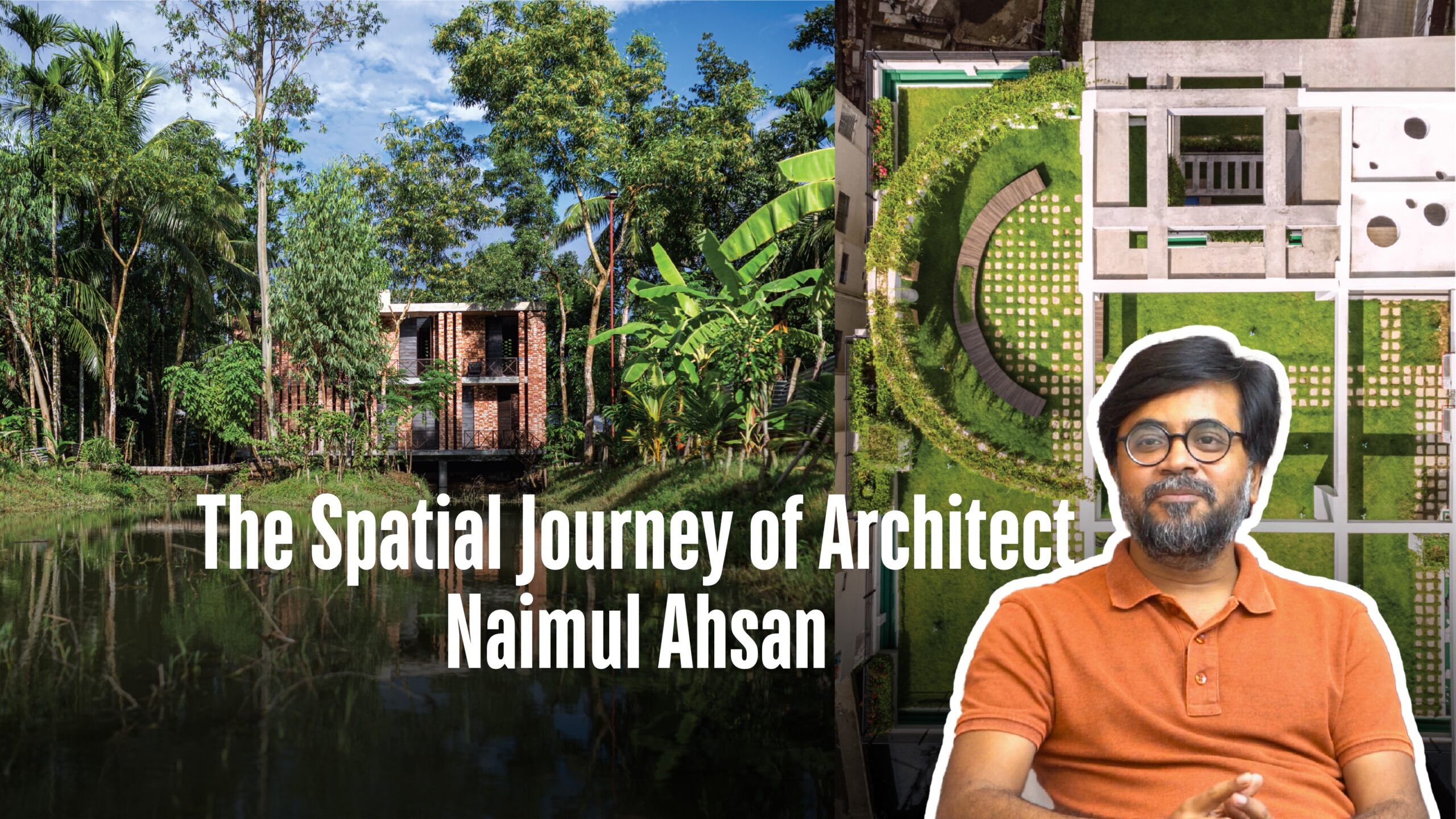

Architecture begins with a dream, but its true value lies in design—making buildings easy to construct, comfortable to inhabit, and meaningful for those who live in them. This is the guiding principle of Naimul Ahsan Khan, founder of Spatial Architects, who spoke about his philosophy on a calm evening in his studio.

For Khan, architecture exists for the people. Simplicity is not just aesthetic but ethical—a way to make spaces accessible, functional, and enduring. His career, marked by both imagination and pragmatism, reflects this belief.

After graduating from BUET in 2006, Khan began his professional journey at VITTI Sthapati Brinda Ltd., while teaching at the University of Asia Pacific, later joining S. Islam Consultants to gain formative experience. Yet even before these formal beginnings, in 2005, he co-founded Matra Architects with three friends, working from a small room at Sher-e-Bangla Hall before moving to Kalabagan. Though the firm dissolved in 2009, it set Khan on the path to independent practice. That same year, he and his wife, architect Farzana Rahman, established Spatial Architects, which has since delivered over 200 projects across Bangladesh.

Khan’s design philosophy is rooted in modernist minimalism, inspired by Mies van der Rohe’s dictum “less is more.” But he translates this principle into a distinctly Bangladeshi context, using simple forms, local materials, and designs that respond to everyday life. Tagore’s words— “simple words are not easy to say”—resonate with him; simplicity in architecture is often the hardest to achieve. Influenced also by Arundhati Roy, who abandoned architecture because of its alienating language, Khan strives to make his work understandable to ordinary people.

This approach is evident in his most celebrated project, Shikor. More than a farmhouse, it is a journey back to rural roots, connecting four generations of the family it was designed for. The design process was deceptively simple: reinterpret elements of rural architecture in a universal, contemporary language. The project transformed the surrounding village, too—muddy roads were paved, solar lights brightened the nights, and a community library was built. “A city family reconnecting with their village changed the village itself,” Khan reflects.

In Chattogram, his Chandrapuray Kichukhon project challenges the dominance of isolated urban apartments. The nine-storey residence, designed for an extended family, revolves around courtyards, gardens, and communal spaces, reviving collective living in a dense city. “We won’t be here forever, but the memories will remain,” the clients told Spatial Architects—a vision the design honours.

Even religious projects follow Khan’s principle of restraint. In Narsingdi, the Baitul Mamur Mosque occupies a modest 55 by 25 feet plot. “It’s such a small piece of land—nothing conventional could be built, so we decided not to force anything,” he explains. Instead, perforated brick walls breathe, and a lightweight metal roof allows air and sunlight to flow freely, creating a spiritual space that feels open and alive.

Khan’s influence extends into education architecture. Working with the Education Engineering Department, he is reshaping rigid, prison-like school layouts into environments that foster joy, safety, and learning—a quiet revolution in the country’s classrooms.

His work has earned international acclaim: First Prize in the Fael Khair Programme International Competition (2009), the Gold Diploma at the Eurasian Prize (2021, Russia), Best of Best at the Architecture Master Prize (2021, California), and First Prize in the NESCO Head Office Complex Competition (2024). Yet for Khan, success is measured not in awards but in client satisfaction. “I want to put my clients first. Their satisfaction is my real achievement,” he says.

His work has earned international acclaim: First Prize in the Fael Khair Programme International Competition (2009), the Gold Diploma at the Eurasian Prize (2021, Russia), Best of Best at the Architecture Master Prize (2021, California), and First Prize in the NESCO Head Office Complex Competition (2024). Yet for Khan, success is measured not in awards but in client satisfaction. “I want to put my clients first. Their satisfaction is my real achievement,” he says.

Sustainability, for him, is local. “Being local is sustainable,” he asserts, advocating for indigenous materials and designs that respond to climate, context, and community. Initially skeptical contractors come to appreciate the clarity of his solutions, and over time, he has built trusted teams of masons and builders who “understand his language”.

Khan is equally outspoken about urban planning in Bangladesh. “We’ve done master plans and detailed area plans, but what we need is urban design,” he insists, warning against overburdening Dhaka and urging development in other cities. He is critical of RAJUK, which he sees as prioritizing promotion over development, emphasizing that regulations must be transparent and serve the public.

Deeply influenced by Bashirul Haque and Mazharul Islam, Khan consults their work when in doubt. He admires contemporaries like Kashef Mahbub Chowdhury and Marina Tabassum, while following global figures such as Tadao Ando. He also champions architectural publications, asking, “A hundred years from now, how will people know what Bangladeshi architecture was like?” For him, publications bridge architects and the wider public.

Optimistic about the younger generation, he says, “They’re smarter than us. They don’t need our advice.” Yet he encourages students to study more about Bangladesh if they intend to practice locally.

Khan’s buildings do not compete for attention—they settle into their surroundings, listening to the land, the people, and the passage of time. For him, architecture is a lived experience, not an abstract statement. By making it easy to build, easy to inhabit, and easy to love, he has created a practice that resonates deeply with the essence of Bangladesh itself.

Written By Arefin Murad