Unveiling New Name Shaping Bangladesh Magazine

Coming Soon

Coming Soon

In a large workshop, the air carries the smell of moist clay and burnt oil.

“It’s not about 10-hole bricks. It’s about a formula for a lifetime investment.”

In the crowded clusters of Dhaka’s architectural offices—where every firm spoke in bold, predetermined tones—finding

A new chapter in early childhood care begins with the opening of the second BRAC

As we turn back towards nature and value the earth more than ever, are we

SEVEN RINGS CEMENT’s Commitment to a Stronger, Greener Bangladesh. In a nation where infrastructure is

The Building Technology & Ideas Ltd (bti), a real estate developing company in Bangladesh, started

What began as a modest idea in mid-2017—to provide home-service tailoring for people constrained by

In the quiet folds of Kushtia’s Kumarkhali upazila, just 20 kilometres away from the bustling

Dhaka’s winter evenings are about to take on a new glow as Aarong ushers in

Day two of the global events of the Institute of Architects Bangladesh (IAB) — the

The Institute of Architects Bangladesh (IAB) inaugurated the Bangladesh ArchSummit 2025 today, December 11.

Bangladesh is quietly rewriting its economic story. Once known primarily for its ready-made garments, the

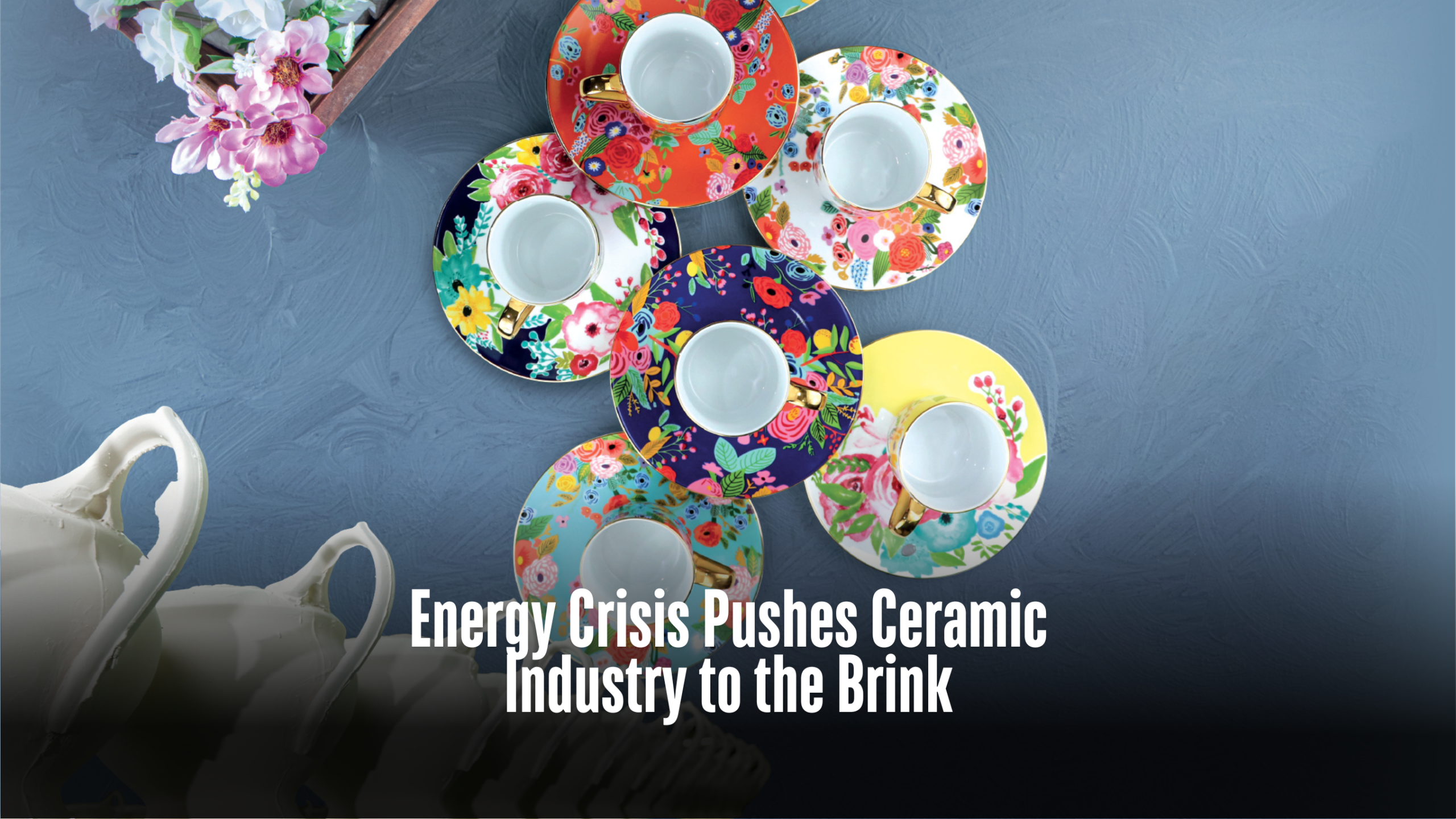

Bangladesh’s ceramic industry is facing one of its toughest periods in decades, as soaring gas

Bangladesh’s meteoric rise in the global garment industry has long been admired, and now a

Architect Marina Tabassum has carved a luminous path that transcends architecture and redefined design as

Once a quiet corner of the industrial map, Bangladesh’s ceramic sector has sculpted its way

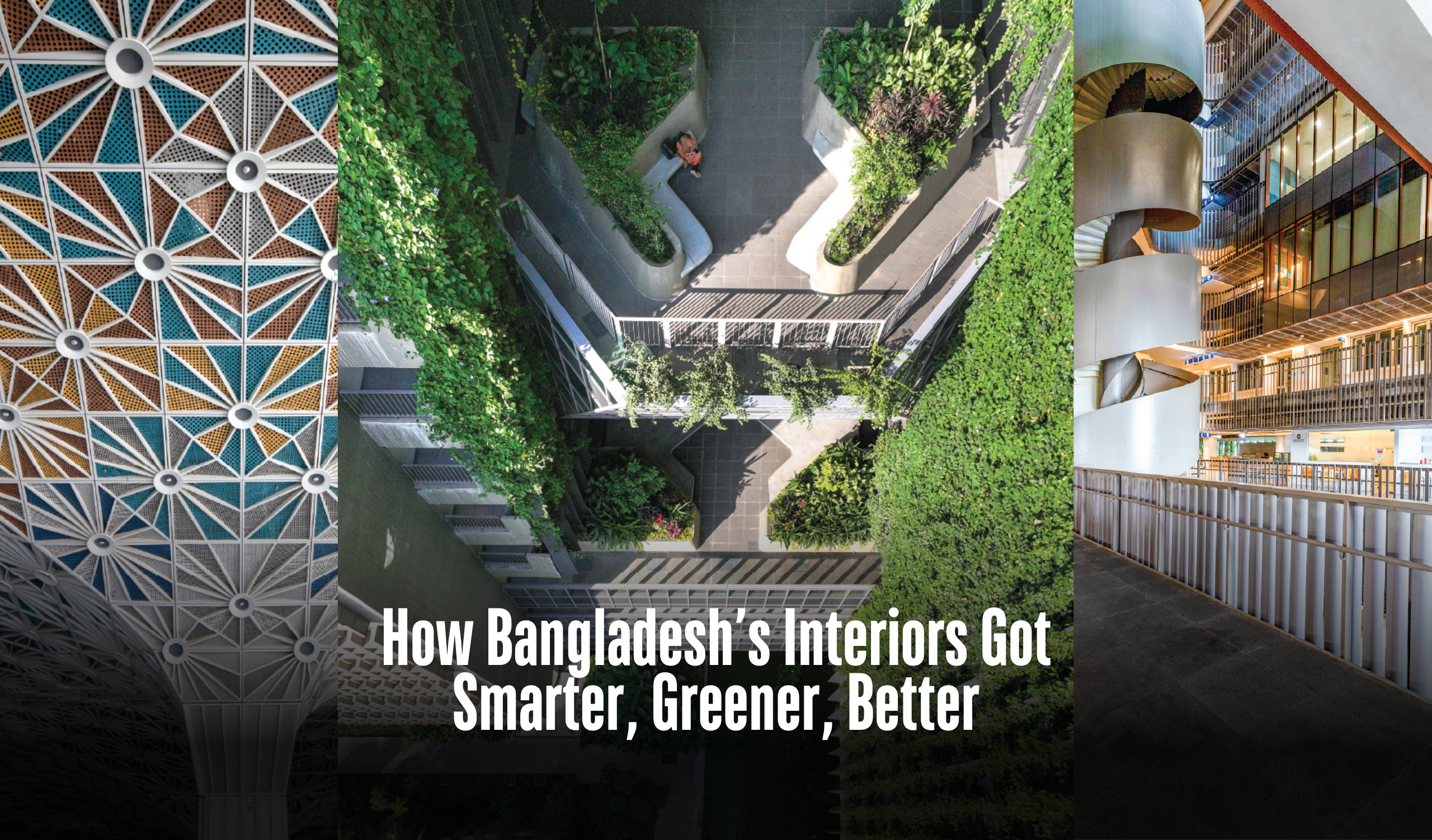

Over the past decades, Bangladesh’s interior sector has undergone a steady evolution. This progressive transformation

Bruised by inflation, foreign exchange volatility, and a surge in non-performing loans, Bangladesh’s banking

Coming Soon

In a large workshop, the air carries the smell of moist clay and burnt oil. Before a single bone china plate reaches the station of Morium Begum or Kamrun Nahar, it has already gone through many steps. It has been shaped by machines, fired until it is as hard as stone, and covered in liquid transparent glaze. But in the final stage of its creation, the loud sounds of industry fade. The atmosphere becomes quiet and focused. Here, hands that know the journey from raw clay to finished vessel perform the most delicate work. These are the hands of artisans. They guide thin, fragile decals onto smooth ceramic surfaces. Each touch is important. Each movement is a blessing on products that will travel to dinner tables around the world. These hands belong to Morium Begum and Kamrun Nahar. They are senior workers, known as “Uchha Dakkhya”—high-skilled artisans. Their lives are deeply connected to this place. Morium has worked in the Export Decoration Department for 25 years. Kamrun has spent 22 years in Bone China Decoration. Their story is not about mass production. It is about careful, patient work and the building of a future. “I’ve been working here for 25 years,” says Morium. Her voice carries conviction. It is more than loyalty to a job. “It doesn’t even feel like we are at a job.” In Bangladesh, factory work is often temporary and difficult. Many workers move from one place to another, facing harsh conditions. So what makes this factory different? What unwritten promise has turned it into a home for these women for more than two decades? The answer is not only in the products they make. It is in the lives they have built through this work. A Day’s Work: The Rhythm of the Kiln In the wide world of ceramic manufacturing, the decoration department is special. It is where the object finds its soul. It is a major step before completion, the moment when a blank plate or cup becomes something unique. Morium and Kamrun are the guardians of this transformation. Their days follow a rhythm shaped by tens of thousands of hours of practice. The morning begins not with machines, but with quiet preparation. They clean their stations. They arrange their tools. They prepare the raw material: stacks of ceramic ware, called “oil” in factory language. Each piece is carefully wiped to make sure the surface is flawless. Then they turn to the decals. These are intricate designs printed on special paper. The paper is dipped in water. Slowly, the design loosens from its backing. It is ready to be transferred. This is the most delicate moment. They lift the fragile film of colour from the water and slide it onto the ceramic surface. The placement must be perfect. The design must flow with the curves of the cup or bowl. No machine can do this. Only memory, skill, and an artist’s eye guide them. Once the decal is in place, they use a simple rubber tool. With gentle strokes, they press out every tiny air bubble and drop of water. “The design is placed on the ware, and then a rubber tool is used to gently rub and set it,” Kamrun explains. Her hands mimic the motion. “After it’s fired, the design is permanent. It won’t even wash off.” The final firing, called Decoration Firing Kiln (oven), makes the design indelible. The decorated pieces go back into the furnace. The heat fuses the decal into the glaze. The process is technical, demanding, and repetitive. Yet the meaning of their work goes beyond mechanics. To understand why they have given their lives to this craft, one must look at the culture of the factory. More Than a Factory: A Foundation for Family For Morium and Kamrun, the factory has been the backdrop of their adult lives. They entered as young women. Over time, they became matriarchs. The culture of the workplace shaped them as much as the skills they learned. It is a culture built on respect. On the factory floor, there are no raised voices. No harsh commands. The sound is a low, cooperative murmur. This is very different from the verbal abuse that they hear is common in other industries. “We don’t speak to anyone harshly here,” Morium says. “We don’t even raise our voices.” This dignity is matched by flexibility. It allows them to be both workers and mothers. When their children had exams or when illness struck, they could take leave for 15 days, even a month. They did not fear losing their jobs. This security is rare. “It’s just like a government job,” Kamrun says. “We can take a month off if we need it. You won’t get that anywhere else.” Support is built into the system. There is a medical centre with doctors and nurses. There is a daycare for young children. But the strongest support comes from the community itself. The women call each other sisters. They share joys and sorrows. One story shows this bond clearly. At the wedding of a cook’s daughter, workers pooled money to help with expenses. The “chairman madam” attended the celebration. Management and staff stood together. In such moments, differences of religion or background disappear. They eat together. They work together. They share goals. This respect, flexibility, and community have created stability. It is the foundation on which Morium and Kamrun have built their lives. It is what allowed them to dream of something lasting for their children. From Artisans to Architects of the Future The true measure of their decades of labour is not in the countless plates and cups they have decorated. It is in the futures they are building. Their hands have shaped clay, but they have also shaped possibilities. Morium is now the sole provider for her family. Her husband, once a worker at

Two projects from Bangladesh — BRAC University and the Zebun Nessa Mosque — have been shortlisted among 52 projects worldwide for the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) International Awards for Excellence 2026. Celebrating outstanding architecture from 18 countries, the biennial awards highlight design that addresses global challenges, including climate change, limited resources, social equity, and rapid urban growth. The shortlist features projects from five continents, ranging from net-zero industrial hubs to refugee art centres. The list includes projects from global practices such as David Chipperfield Architects (UK/Germany), Foster + Partners (UK), Snøhetta (Norway/USA), Hassell (Australia), and WOHA (Singapore), alongside noteworthy boutique firms including MAKER architecten (Belgium) and Studio Mumbai (India). Neil Gillespie, Awards Group Chair, said: “The RIBA International Awards for Excellence celebrate incredible diversity and creativity across the world. These projects show how architects can respond to complex social, cultural, and environmental challenges —

More than a century has passed after the legendary Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain penned her iconic Sultana’s Dream (1905). To mark the 120th anniversary of the book—and its recognition in UNESCO’s Memory of the World (Asia-Pacific) register—the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka has launched Reimagining Sultana’s Dream, a group exhibition featuring works by twenty artists. The exhibition, neatly curated by Sharmille Rahman, is jointly organized by the Liberation War Museum and Kalakendra with support from Libraries Without Borders and Alliance Française de Dhaka and runs at the museum’s sixth-floor temporary gallery until March 7. Rokeya’s original narrative imagined a world where women govern society through reason, care, and scientific ingenuity, while men remain confined to domestic seclusion. The satire was sharp, the politics unmistakable: power, she argued, is not inherently masculine; it is merely monopolized. Yet, as visitors move through this exhibition’s sprawling installations, photographs, textiles, videos, and conceptual works, one realizes that the distance between Rokeya’s dream and contemporary reality remains narrower than it should be—and far more troubling than we might like to admit. The exhibition’s strength lies in its multiplicity of voices, and together, the artworks blur the boundary between literary homage and contemporary social critique. The artists visualized women’s invisible labor, persistent structural discrimination, and the resilience forged through everyday struggle. Many installations dwell on domesticity, wage inequality, bodily autonomy, and the silent endurance that sustains both households and economies. They do not romanticize womanhood; instead, they interrogate how patriarchy shapes aspiration, opportunity, and even imagination. For example, a striking, suspended photographic installation that features suspended images of men, where words such as “violence,” “wages,” “women’s labor,” and “possibility” are inscribed on their bodies. The images hang from the ceiling like a suspended interrogation. Are all these accusations aimed at men, women, or society at large? The artist framed the artwork as a question: “Perhaps you are the hunter, or the hunted.” This ambiguity implicates the audience to confront their position within systems of power. Another installation draws on Chakma weaving traditions—offering a reminder that alternative models of gender coexistence have long existed within South Asia’s indigenous cultures. The artwork gently counters the assumption that patriarchy is universal and immutable, proposing instead that social arrangements are historical choices—capable of being rewritten. Nearby, another artwork evokes the emotional terrain of women whose dreams remain pressed beneath social expectation, while another artwork centers working-class women, pairing video art with written testimonies that echo fatigue, hope, and perseverance. Rather than presenting women as abstract symbols, the piece insists on specificity—on listening closely to lived experience. Similarly, another installation uses repetition of sound to halt the visitor mid-step, demanding attention to voices often ignored. Collectively, all the artworks from the 20 artists reveal a paradox. While Sultana’s Dream envisioned a radical overturning of patriarchal norms, today’s artists find themselves still grappling with remarkably similar realities. The exhibition suggests that Rokeya’s satire was not merely ahead of its time—it remains unfinished business. But the show does more than just honor the feminist legacy; it questions its limits. Can art about women’s struggle transcend gallery walls and urban cultural circles? Or does it risk becoming another enclosed space where pain is aestheticized rather than transformed? In this exhibition, women’s voices, bodies, protests, and questions take on material form—etched in fabric, projected on walls, suspended in midair; it does not offer easy resolutions; instead, it insists that Rokeya’s dream must be reread, revised, and challenged continuously as an evolving dialogue. Ultimately, the exhibition reminds us that Begum Rokeya’s feminist utopia is not a destination but a process—one that requires vigilance, critique, and collective imagination. She dreamed of a world liberated from gendered injustice. So the exhibition asks a harder, more urgent question: are we any closer to living in it? Written by Shahbaz Nahian

The lesser-known dimension of the late eminent artist Mohammad Kibria comes into view through a solo exhibition titled ‘An Artist’s Compilation: 84 Unseen Original Works (1980–2006)’, currently on display at Kalakendra, Dhaka. The exhibition presents 84 small-format works on paper, many of which are being exhibited publicly for the first time. Supported by City Bank, the exhibition is organized jointly by Kalakendra and the artist’s family to mark what would have been his 97th birth anniversary. The works in the exhibition are drawn from a handbound folio that Kibria himself compiled over more than two decades, suggesting a private archive shaped with care, discipline, and a quiet sense of purpose. What distinguishes this exhibition is the revelation of a more introspective Kibria. These pieces operate on an intimate scale. Most are created on letter-sized paper using pencils, pens, watercolors, pastels, etching, oil, mixed media, and collage. Printed paper fragments, clipped magazine pages, textured layers, and restrained color interventions are prevalent throughout. Several collages are composed of dark grounds—black, brown, or grey—onto which textured scraps and subtle tonal shifts have been assembled. In some places, small dabs of color punctuate the surface, while elsewhere, delicate linear gestures hover like afterthoughts. All these smaller-scale artworks emphasize restraint, nuance, and philosophical calm. Several compositions also evoke an archaeological sensibility—surfaces that appear weathered by time, such as fragments of ancient walls, corroded metal plates, or fading manuscripts. One particularly striking piece features a golden, matte texture that recalls eroded plaster, while another one features sharp white marks against a deep black field, resembling streaks of light piercing the darkness. Furthermore, the absence of individual titles reinforces the sense that these works were never meant to be spectacles. Instead, they function like notes, meditations, or private experiments—records of sustained inquiry rather than declarations intended for the market or gallery wall. Kibria himself selected and arranged these 84 works into a folio, binding them by hand and designing the cover. It remains unclear whether he intended to collect it for a future exhibition or publication. However, the artist’s particular focus on form, sequencing, and preservation is evident. Beyond the artworks themselves, the folio also contains personal materials—letters, exhibition catalogues, photographs, and even a drawing gifted by fellow artist, another legend, Kamrul Hassan. Also on view is a letter appointing Kibria as an emeritus professor at the University of Dhaka in 2008. Together, these artifacts frame the folio as a time capsule that traces both artistic evolution and lived history. Born on January 1st, 1929, in Birbhum (now in West Bengal, India), Mohammad Kibria graduated from the Calcutta Art College in 1950 before moving to Dhaka. He then joined the newly established Dhaka Art College in 1954. Later pursued advanced studies in Japan from 1959 to 1962 on a government-sponsored scholarship. Over the decades, he established himself as a master printmaker, painter, and educator, retiring from the Institute of Fine Arts at the University of Dhaka in 1987. He received major national honors, including the Ekushey Padak and the Independence Award, and remained a revered figure until his death on June 7, 2011. At a time when Kibria’s works have become increasingly scarce in public galleries, many now residing in private collections, this exhibition offers a rare opportunity to encounter a less visible chapter of his artistic journey. It reframes him as both a monumental modernist and a quiet chronicler of time, texture, and thought. In the midst of Dhaka’s urban intensity, Kibria’s folio opens a slower, more meditative world—one in which paper, pigment, and memory converse in subdued tones. The exhibition does not merely commemorate an artist’s legacy; it expands it, revealing a body of work that is at once archival, philosophical, and strikingly alive. The exhibition will run until February 2nd, 2026, open daily from 4 pm to 8 pm, with support from City Bank. Written by Shahbaz Nahian

Gallery Plat-forms is hosting ‘Beyond the Veil’ – 3rd solo exhibition by M F I Mazumder Shakil. In this exhibition, the artist presents the ancient medium of woodcut in a fresh, contemporary artistic form. A total of 24 woodcut prints are on display which includes 8 large-scale works. The exhibition began on November 9 and has now been extended until December 13, with visiting hours from 11 am to 8pm. As noted by Gallery Plat-forms, in ‘Beyond the Veil’, Shakil revives the long-format woodcut to explore a world both intimate and exclusive. Through sweeping panels in amber, midnight blue, and stark monochrome, a woman emerges through fabric, fold and shadow. The veil becomes a threshold rather than concealment, inviting us to see without seeing. Each cut and layer conjures the textures of cloth and memory, secrecy and freedom. Part portrait, part landscape of the unseen. Beyond the veil transcends identity to question how we perceive, what lies hidden. Rooted in tradition yet distinctly contemporary. Shakil’s work reimagines the politics of visibility and expands the language of global printmaking. “My work is primarily in printmaking – specifically woodcut. I begin by drawing on plywood or any other board, then carve the block using woodcut tools based on the distribution of light and shadow. After that, I apply ink to the block with a roller through various processes, and finally transfer the print onto paper. Depending on the size, completing a single piece can take several months,” explains Shakil. “I have participated in various exhibitions, art camps, and art fairs both in Bangladesh and abroad. In the future, I plan to organize solo exhibitions outside the country as well. In recent times, young artists in Bangladesh have been tirelessly pursuing creative practice, and their works have already received significant recognition on the international stage. However, the overall acceptance of fine arts within the country has yet to reach the desired level. I remain hopeful that with proper patronage and support, our artists will be able to present Bangladesh’s artistic heritage to the world with even greater distinction,” the artist further adds. Mohammed Fakhrul Islam Mazumder, a Bangladeshi artist born in Comilla in 1989. He completed his M.F.A and B.F.A in Printmaking from the Faculty of Fine Arts at Dhaka University in 2016 and in 2014. Mazumder has held two solo exhibitions— “Obscure Beauty” (GalleryChitrak, 2023) and “The Odyssey of the Soul” (Zainul Gallery, 2018). His art has been showcased widely across Asia,Europe, and Australia, including major exhibitions in Japan, China, Thailand, Korea, India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. He has received numerous national and international awards such as the 26th Berger Young Painters’ Award (2022), Excellent Works Award, COP15 Global Art & Design Competition, China (2022), 2nd International Print Biennale Award, India (2021), and the Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin Award (2019). Mazumder’s works are part of collections at the China Printmaking Museum, Ino-cho Paper Museum (Japan), Bengal Foundation, and Lalit Kala Academy (India). He has also participated in several artist residencies, including the Chitrashala International Artist Residency in India and Kali Artist Residency at Cosmos Atelier 71, Bangladesh. Currently, Mazumder continues to experiment with layers of print, texture, and form to reflect the subtle interplay between the visible and the unseen. Through this exhibition, Shakil opens a new doorway not only to beauty but also to perception. His works, imprinted with the labor of hand-carved marks on solid wood surfaces, unfold into a poetry of light and shadow. This exhibition is part of Gallery Plat-forms’ commitment to presenting Bangladeshi artists who bring together heritage and contemporaneity, offering them anew to the global stage. Written by Tasmiah Chowdhury Photo Credits Sarmin Akter lina Gallery plat-Forms

The 18th Bangladesh International Plastics, Printing and Packaging Industry Fair (IPF-26) will take place from January 28 to 31, 2026, at the International Convention City Bashundhara (ICCB) in Dhaka. The event is jointly organised by the Bangladesh Plastic Goods Manufacturers & Exporters Association (BPGMEA) and Yorkers Trade & Marketing Service Co., Ltd., with show management by Chan Chao International Co., Ltd. The fair will feature 400 exhibitors across 800 booths, representing over 18 countries and regions. Exhibitors will occupy 18,000 square metres of space, making it one of the largest industrial gatherings in Bangladesh. Countries participating include Austria, China, India, Indonesia, Italy, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, the United States, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. IPF Bangladesh 2026 presents a full value-chain showcase covering core production technologies, materials, and downstream applications, enabling visitors to evaluate complete manufacturing solutions in one venue. Organisers said the focus is on demonstrating how plastics can support sustainable farming practices and help address climate and food security challenges. Bangladesh’s plastic industry is valued at $2.99 billion and is expanding at an annual growth rate of more than 20 percent.

The stage is all set for the 25th Dhaka International Yarn & Fabric Show 2026 – Winter Edition, which will be held from January 28 to 31, 2026, at the International Convention City Bashundhara (ICCB). The exhibition marks the 25th anniversary of Bangladesh’s longest-running B2B yarn and fabric sourcing platform, and it will be organised by CEMS-Global USA in association with the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT-TEX). As part of CEMS-Global USA’s textile series of exhibitions held across three continents, the Dhaka International Yarn & Fabric Show is regarded as one of the most established platforms for textile manufacturers and suppliers. The event will feature yarns, fabrics, denim, accessories, trims, and textile technologies, bringing together global manufacturers, suppliers, and buyers. Organisers said the event is positioned as a key sourcing platform for Bangladesh’s textile and apparel industry, which is valued at more than $47 billion and has established the country as the world’s second-largest apparel exporter. Exhibitors from multiple countries will present new innovations and sourcing opportunities, with a focus on advanced yarn technologies, sustainable fabric solutions, and textile machinery, according to the website of the showcase. The exhibition will provide opportunities for business networking, technology transfer, and market expansion, while reinforcing Bangladesh’s role as a growing global textile hub. Visitors will be able to explore functional fabrics, natural fibres, denim, embroidery, artificial leather, and home textiles. The show is designed to connect international suppliers with local manufacturers and exporters, encouraging collaboration and strengthening Bangladesh’s competitiveness in global markets. The exhibition will run daily from 10:00 am to 7:00 pm at the International Convention City Bashundhara (ICCB), with registration required for entry. Industry representatives said the show comes at a time when Bangladesh’s textile sector is expanding rapidly and diversifying into new product categories to meet global demand. The 25th edition also coincides with the 8th Denim Bangladesh exhibition, which will highlight developments in denim and casual wear. Together, the two events will cover the full spectrum of textile sourcing and production, offering buyers and suppliers a comprehensive view of Bangladesh’s capabilities. Organisers emphasized that the show’s 25-year legacy demonstrates its importance to the industry and its role in supporting Bangladesh’s rise as a major textile and apparel exporter. They said the 2026 edition will continue to strengthen Dhaka’s position as a centre for textile trade and innovation in South Asia. Written By Nibir Ayaan

In a major step toward sustainable industrial growth, AkijBashir Group has entered into a strategic partnership with the Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL) to promote energy efficiency and renewable energy across its operations. The collaboration, formalized at an event held at Sheraton Dhaka, marks a significant milestone in advancing green industrial practices in Bangladesh. AkijBashir Group has been funding several sustainability projects in the last couple of years through its Energy Efficiency and Rooftop Solar financing programs funded by IDCOL. These projects have enabled the deployment of industrial rooftop solar capacity of more than 90MWp, of which over 60MWp has been deployed and has become one of the largest solar portfolios in the private sector in Bangladesh. One of the highlights of the joint venture is a pioneer project of Janata Jute Mills Ltd. in Boalmari, Faridpur, that will become the first in the world to be a fully operational jute mill using renewable energy by the first quarter of 2026. In the long-term sustainability, the Group targets to produce a renewable energy of 1,000 MWh every day by 2027. During the event, AkijBashir Group Managing Director, Mr. Taslim Md. Khan, and IDCOL Executive Director and CEO, Mr. Alamgir Morshed, emphasized the role of collaboration in the development of the future of the low-carbon industry. AkijBashir Group is determined to be 100% renewable in all its manufacturing plants by the year 2030, which is in line with its vision Beyond Tomorrow- impetus on sustainability, innovation, and industrial perfection.

A global initiative to promote investor education and protection is underway as World Investor Week 2025 runs from October 6 to 12, led by the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO). Now in its latest edition, the campaign aims to raise awareness about the importance of financial literacy, responsible investing, and the protection of investors in an increasingly digital and complex financial landscape. The global campaign features participation from securities regulators, exchanges, financial organisations, and educators across six continents, with events tailored to national and regional contexts. Activities include public awareness drives, webinars, training sessions, and outreach campaigns designed to help investors make informed decisions and guard against fraud. A flagship feature of the campaign is the “Ring the Bell for Financial Literacy” initiative, held in collaboration with the World Federation of Exchanges (WFE). Stock exchanges around the world symbolically “ring the bell” to demonstrate their commitment to investor education and market transparency. Focus on Fraud, Digital Threats, and Investor Awareness This year’s programme includes a strong emphasis on the emerging threat of digital fraud, particularly those involving artificial intelligence and online scams. On October 7, U.S. regulators including the National Futures Association (NFA), FINRA, and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) hosted a webinar titled “Deconstructing to Disrupt Fraud”, which was a two-part event featuring Dr. Arda Akartuna. The session explored how AI technologies are being weaponised by fraudsters, and how regulators and investors can respond with vigilance and education. In Indonesia, the national financial regulator Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK) is hosting a regional webinar on October 9 titled “Empowering Investors: Invest Wisely and Stay Safe from Fraud and Scams.” The event features speakers from IOSCO’s Committee on Retail Investors and will discuss practical strategies to improve retail investor protection. Investor education for older adults is also a priority in this year’s campaign. In the United States, the CFTC, FBI, and AARP have partnered on outreach aimed at Americans aged 50 and older, focusing on helping them identify and avoid scams. The organisers report that over 250 participants registered for this dedicated session. Global Backing and Institutional Support World Investor Week is supported by a wide range of international partners, including: The World Bank OECD G20 Sustainable Stock Exchanges (SSE) Initiative International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation European Fund and Asset Management Association (EFAMA) These partnerships reinforce IOSCO’s broader mission to promote not only awareness, but also long-term behavioural change among investors and institutions globally. As the global standard-setter for securities regulation, IOSCO collaborates closely with the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the G20 to ensure that investor protection remains a key pillar of global financial integrity and stability. Building Resilience in a Complex Investment Landscape With financial markets rapidly evolving due to digitisation, AI technologies, and cross-border investment platforms, retail investors are exposed to new complexities and risks. World Investor Week serves as a timely reminder of the need for robust financial education, stronger regulatory safeguards, and proactive public engagement. As the campaign continues through October 12, organisers hope to empower individuals with the knowledge to navigate risks, detect fraud, and contribute to more resilient financial markets across all levels of society. Written By Nibir Ayaan

The ongoing exhibition titled Timber Tales at La Galerie, Alliance Française de Dhaka, invites audiences to experience the collaborative journey of three emerging artists who explore memory, process, and material through the art of woodcut printmaking. Within the exhibition, a faint, earthy scent of wood and ink hangs in the air. Walking into the gallery, some might find themselves pausing longer than expected, tracing the grain of the wood, as if searching for their own stories between the lines. The exhibition features three artists—Rakib Alam Shanto, Shakil Mridha, and Abu Al Naeem—who express individuality through their woodcut prints. This contemplative exhibition is running from June 17 to June 25, 2025. Curated by the artists themselves, the exhibition reimagines the possibilities of woodcut as a medium. Here, the tactile intimacy of carved timber meets the visual language of reflection, nostalgia, and search. As you wander through the space, individual voices emerge. Shakil Mridha’s work, with its minimalistic yet profound geometric forms, feels like a contemporary ode to Bangladeshi folk art, skillfully abstracting familiar motifs. Rakib Alam Shanto’s large-scale black and white pieces command attention, a powerful revival of a classic tradition, showcasing his remarkable focus. And Abu Al Naeem’s pieces, often abstract, subtly reveal hidden figures, reflecting his continuous exploration of materials and techniques. Each artist, in their unique way, elevates woodcut beyond mere reproduction, transforming it into a medium of profound personal expression. And through that expression, each of their work reflects the heart of the creative process, where stories are carved into existence. At the heart of Timber Tales is a tribute to beginnings, to the mentor who shaped them, and to the space where it all began. Their acknowledgement of Professor Md. Anisuzzaman, whose generous guidance helped steer their vision, reveals the deeply collaborative ethos of the show. “This is where it all began—for the three of us,” reads a line from the exhibition note, underscoring the intimate bond between craft, community, and coming-of-age. In an era of digital immediacy, there’s something revolutionary about the deliberate slowness of woodcut. And the three artists have breathed new life into the ancient art of woodcut. More than just a technique, it’s a dialogue between human touch and natural materials. Each frame holds a deeper narrative of tireless dedication—the careful selection of wood, the precise cuts, the methodical inking, and the final, expectant press. Open to all and continuing until 25 June 2025, Timber Tales will leave visitors with more than just images on paper. In a city rushing to reinvent itself, the exhibition feels like a pause, a reminder of our roots with a sense of belonging—to the artists, to the materials, and to the timeless, meditative act of making. Written By Samira Ahsan

The heart of the order is the new Continua+ 2180, equipped with cutting-edge digital decoration solutions Following installation of the new SACMI Continua+ 2180, Royal (Vietnam) becomes the first Asia-Pacific group to equip itself with SACMI technology for on-surface and through-body slab decoration. Moreover, the line is digitally coordinated with Deep Digital solutions, supplied here in an all-round configuration: two DHD digital wet decorators and a DDG digital grit-glue decorator. The new line will allow Royal to expand its range by creating new products with unmatched three-dimensional ‘material’ effects, all the strength and durability of ceramic, and a look that mirrors the aesthetics of natural materials. This important investment decision was not motivated by the innovative forming and decorating technology alone: equally crucial was SACMI’s ability to supply the complete plant, from body preparation (with two spray dryers and relative spray-dried powder conveying/storage systems) to firing in a high-efficiency roller kiln. Already strongly positioned on international markets, Royal has now – with SACMI – taken quality in these high-added-value segments to the next level. For example: the manufacture of ceramic countertops and furnishing accessories, with all the advantages Continua+ has to offer in terms of versatility, productivity and fully flexible control of size and thickness, in coordination with all the digital devices on the line.

The curtain has drawn on the remarkable journey of Akij Tableware Art of Plating: Season 2, the pioneering reality show that reimagined tableware as a medium for creative expression and showcased the artistry of modern plating. Following weeks of intense competition, visually striking presentations, and exceptional culinary performances, the grand finale—held on May 16, 2025—served as a fitting conclusion to a season defined by innovation and excellence. Md. Golam Rabby emerged victorious as the champion, taking home the Plating Maestro title along with BDT 10,00,000 along with a professional plating course, national media exposure, and an exclusive Akij Tableware dinner set. The competition was fierce, with equally impressive performances by the runners-up: Iffat Jerin Sarker, awarded Plating Icon (1st Runner-up), received BDT 5,00,000; Dr. Rawzatur Rumman, crowned Plating Maverick (2nd Runner-up), won BDT 3,00,000; Homayun Kabir and Nawsheen Mubasshira Rodela, honored as Plating Masterminds (4th and 5th place respectively), each received BDT 1,00,000. Hosted across Banglavision, RTV, Deepto TV, and streaming on Chorki, Akij Tableware Art of Plating: Season 2 captivated audiences nationwide with its unique blend of tradition and innovation. Contestants turned beloved dishes into visual and gastronomic masterpieces, judged on aesthetics, technique, and culinary understanding. Akij Tableware Art of Plating: Season 2 redefined how we experience food—elevating it from everyday necessity to a dynamic, visual art form. The show celebrated creativity, precision, and innovation, turning each plate into a canvas where flavor met form. Throughout the season, contestants pushed boundaries, transforming ingredients into stunning, story-driven presentations that delighted both the eyes and the palate. More than a competition, this season launched a new movement in culinary expression, inspiring audiences to rethink how food is seen, served, and appreciated. And the journey isn’t over—a new season is coming soon, promising fresh talent, bold ideas, and next-level plating artistry. To stay updated on what’s next, follow www.aop.com.bd and join the evolution of food into a true visual experience.

The ongoing exhibition titled Timber Tales at La Galerie, Alliance Française de Dhaka, invites audiences to experience the collaborative journey of three emerging artists who explore memory, process, and material through the art of woodcut printmaking. Within the exhibition, a faint, earthy scent of wood and ink hangs in the air. Walking into the gallery, some might find themselves pausing longer than expected, tracing the grain of the wood, as if searching for their own stories between the lines. The exhibition features three artists—Rakib Alam Shanto, Shakil Mridha, and Abu Al Naeem—who express individuality through their woodcut prints. This contemplative exhibition is running from June 17 to June 25, 2025. Curated by the artists themselves, the exhibition reimagines the possibilities of woodcut as a medium. Here, the tactile intimacy of carved timber meets the visual language of reflection, nostalgia, and search. As you wander through the space, individual voices emerge. Shakil Mridha’s work, with its minimalistic yet profound geometric forms, feels like a contemporary ode to Bangladeshi folk art, skillfully abstracting familiar motifs. Rakib Alam Shanto’s large-scale black and white pieces command attention, a powerful revival of a classic tradition, showcasing his remarkable focus. And Abu Al Naeem’s pieces, often abstract, subtly reveal hidden figures, reflecting his continuous exploration of materials and techniques. Each artist, in their unique way, elevates woodcut beyond mere reproduction, transforming it into a medium of profound personal expression. And through that expression, each of their work reflects the heart of the creative process, where stories are carved into existence. At the heart of Timber Tales is a tribute to beginnings, to the mentor who shaped them, and to the space where it all began. Their acknowledgement of Professor Md. Anisuzzaman, whose generous guidance helped steer their vision, reveals the deeply collaborative ethos of the show. “This is where it all began—for the three of us,” reads a line from the exhibition note, underscoring the intimate bond between craft, community, and coming-of-age. In an era of digital immediacy, there’s something revolutionary about the deliberate slowness of woodcut. And the three artists have breathed new life into the ancient art of woodcut. More than just a technique, it’s a dialogue between human touch and natural materials. Each frame holds a deeper narrative of tireless dedication—the careful selection of wood, the precise cuts, the methodical inking, and the final, expectant press. Open to all and continuing until 25 June 2025, Timber Tales will leave visitors with more than just images on paper. In a city rushing to reinvent itself, the exhibition feels like a pause, a reminder of our roots with a sense of belonging—to the artists, to the materials, and to the timeless, meditative act of making. Written By Samira Ahsan

The heart of the order is the new Continua+ 2180, equipped with cutting-edge digital decoration solutions Following installation of the new SACMI Continua+ 2180, Royal (Vietnam) becomes the first Asia-Pacific group to equip itself with SACMI technology for on-surface and through-body slab decoration. Moreover, the line is digitally coordinated with Deep Digital solutions, supplied here in an all-round configuration: two DHD digital wet decorators and a DDG digital grit-glue decorator. The new line will allow Royal to expand its range by creating new products with unmatched three-dimensional ‘material’ effects, all the strength and durability of ceramic, and a look that mirrors the aesthetics of natural materials. This important investment decision was not motivated by the innovative forming and decorating technology alone: equally crucial was SACMI’s ability to supply the complete plant, from body preparation (with two spray dryers and relative spray-dried powder conveying/storage systems) to firing in a high-efficiency roller kiln. Already strongly positioned on international markets, Royal has now – with SACMI – taken quality in these high-added-value segments to the next level. For example: the manufacture of ceramic countertops and furnishing accessories, with all the advantages Continua+ has to offer in terms of versatility, productivity and fully flexible control of size and thickness, in coordination with all the digital devices on the line.

The curtain has drawn on the remarkable journey of Akij Tableware Art of Plating: Season 2, the pioneering reality show that reimagined tableware as a medium for creative expression and showcased the artistry of modern plating. Following weeks of intense competition, visually striking presentations, and exceptional culinary performances, the grand finale—held on May 16, 2025—served as a fitting conclusion to a season defined by innovation and excellence. Md. Golam Rabby emerged victorious as the champion, taking home the Plating Maestro title along with BDT 10,00,000 along with a professional plating course, national media exposure, and an exclusive Akij Tableware dinner set. The competition was fierce, with equally impressive performances by the runners-up: Iffat Jerin Sarker, awarded Plating Icon (1st Runner-up), received BDT 5,00,000; Dr. Rawzatur Rumman, crowned Plating Maverick (2nd Runner-up), won BDT 3,00,000; Homayun Kabir and Nawsheen Mubasshira Rodela, honored as Plating Masterminds (4th and 5th place respectively), each received BDT 1,00,000. Hosted across Banglavision, RTV, Deepto TV, and streaming on Chorki, Akij Tableware Art of Plating: Season 2 captivated audiences nationwide with its unique blend of tradition and innovation. Contestants turned beloved dishes into visual and gastronomic masterpieces, judged on aesthetics, technique, and culinary understanding. Akij Tableware Art of Plating: Season 2 redefined how we experience food—elevating it from everyday necessity to a dynamic, visual art form. The show celebrated creativity, precision, and innovation, turning each plate into a canvas where flavor met form. Throughout the season, contestants pushed boundaries, transforming ingredients into stunning, story-driven presentations that delighted both the eyes and the palate. More than a competition, this season launched a new movement in culinary expression, inspiring audiences to rethink how food is seen, served, and appreciated. And the journey isn’t over—a new season is coming soon, promising fresh talent, bold ideas, and next-level plating artistry. To stay updated on what’s next, follow www.aop.com.bd and join the evolution of food into a true visual experience.