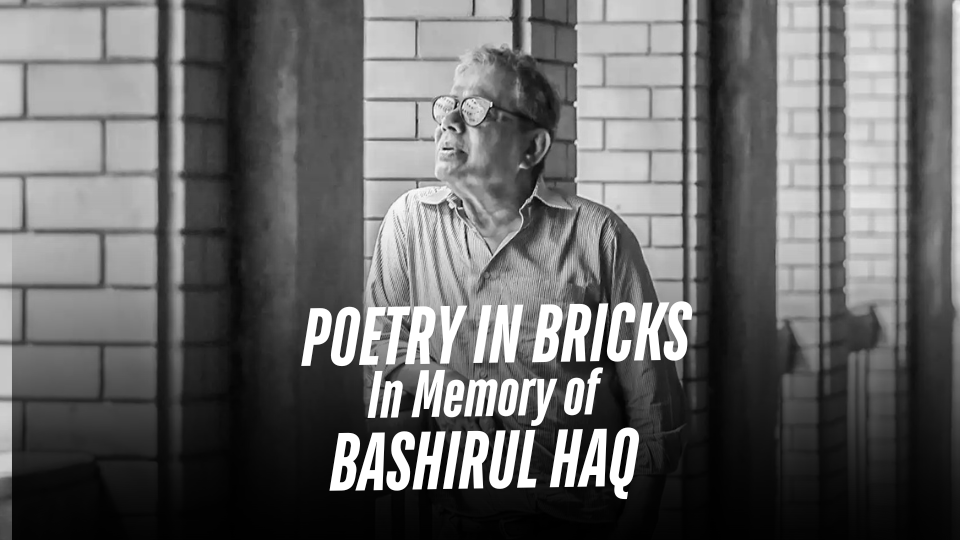

Poetry in brick – is how a happy client described the house that Bashirul Haq had designed for them. This short write-up is an effort to describe this poetry and the process by which it was created.

Bashirul Haq (1942-2020) had the good fortune to grow up in an idyllic rural environment, where he, unbeknownst to himself, imbibed how people could live in close harmony with the environs, where human habitation merged seamlessly with its surroundings, without disturbing it in any way. The eastern region of Bangladesh, and Brahmanbaria in particular, where his village lay 6 miles away from the town, is notoriously overpopulated. But from afar, from a car or a bus, the landscape is not crowded by people, and villages are tucked away behind clumps of trees, by paddy fields or water bodies. This is the simple living style that Bashirul Haq, as an architect, tried to adapt and express in his urban buildings.

Architecture and architects in Bangladesh are carrying on the quest that Bashirul Haq was on—to find a grammar and an idiom of building that speaks to our landscape, that carries on our building traditions, yet is modern and contemporary, and responds to the needs of its users.

Bashirul Haq used to describe his life as a series of happy coincidences. Most prominent amongst these coincidences, he felt, was his choice of profession. He discovered that designing buildings could be a profession as he sat browsing the USIS library as an intermediate student at Dhaka College. This set him out on a search for where he could pursue this subject. BUET had yet to start its department, and this led him to the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore and to apply for an interwing scholarship.

This was a great career move, as the NCA was in search of a local architectural idiom. Trips to Mohenjo Daro and Harappa organized by the department, studying Mughal building traditions, and being housed in a building that embodied Indo-British architecture, students were encouraged to explore their modes of expression. This early training was honed at the University of New Mexico, where he went for his postgraduate studies. The adobe building patterns there further honed the young architect’s search for design practices that spoke to the environment and a sense of history and tradition.

Returning to Bangladesh in 1977, Bashirul Haq felt that he could translate this training and preparation into practice. He began with small projects, and the ‘poetry in brick’ mentioned earlier was a house built for Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury. From the beginning, he chose brick as the construction material of choice. It sprung from the soil—nothing else could be more indigenous than brick, he would claim. Brick had a long history as a building material in the region, and he felt that the color of the brick and the green surroundings were in total harmony.

His brick buildings were distinctive, but it meant that they appealed to a selective group of clients. However, he stuck to his design principles and always tried to combine the local with the modern. The cost of building was a big concern. In his more institutional buildings, such as the BCIC building, he would look for ways of cutting costs without compromising on aesthetic quality. Glossy materials were not part of his designs. Even the high-rise buildings are quite quiet—they do not draw attention to themselves in any way. The site is used to orient the building as much as possible with its environs.

He was a purist in many ways and did not believe in using brick as surface cladding but as the actual structural material. He would emphasize the maintenance-free nature of brick, which does not need to be repainted or plastered. He spent long hours in making this material more resilient to weather conditions, to make it waterproof, or to prevent the salinity that tends to seep through.

Architecture and architects in Bangladesh are carrying on the quest that Bashirul Haq was on—to find a grammar and an idiom of building that speaks to our landscape, that carries on our building traditions, yet is modern and contemporary, and responds to the needs of its users. Brick remains prominent in the architectural design practice in the country. This preponderance of brick has led, we are told, to great atmospheric pollution. Bashirul Haq would contend that ethical brickmaking processes would minimize this degradation and had a calculation regarding carbon emissions in the production of brick versus that of cement, where the brick was better. He also thought that more efficient methods of production had to be devised, minimizing the effects on climate. He was interested in building with mud and had designed a mud building, which sadly remains unbuilt.

Reinforced bamboo was another material that interested him. He had prepared a book on cyclone-resistant housing in the coastal belt of Bangladesh. This book contains a detailed description of a house in the Cox’s Bazar region, which had withstood the great cyclone of 1991. Bashirul Haq was a thoughtful and creative person who believed that buildings should blend into the existing landscape, rather than stand out as monuments that define the landscape. In today’s world, with environmental issues at the forefront, this is a good architectural principle.

Written by: Professor Firdous Azim

Photo credit: Al Amin Abu Ahmed Ashraf Dolon | Prantography