More than a century has passed after the legendary Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain penned her iconic Sultana’s Dream (1905). To mark the 120th anniversary of the book—and its recognition in UNESCO’s Memory of the World (Asia-Pacific) register—the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka has launched Reimagining Sultana’s Dream, a group exhibition featuring works by twenty artists.

The exhibition, neatly curated by Sharmille Rahman, is jointly organized by the Liberation War Museum and Kalakendra with support from Libraries Without Borders and Alliance Française de Dhaka and runs at the museum’s sixth-floor temporary gallery until March 7.

Rokeya’s original narrative imagined a world where women govern society through reason, care, and scientific ingenuity, while men remain confined to domestic seclusion. The satire was sharp, the politics unmistakable: power, she argued, is not inherently masculine; it is merely monopolized.

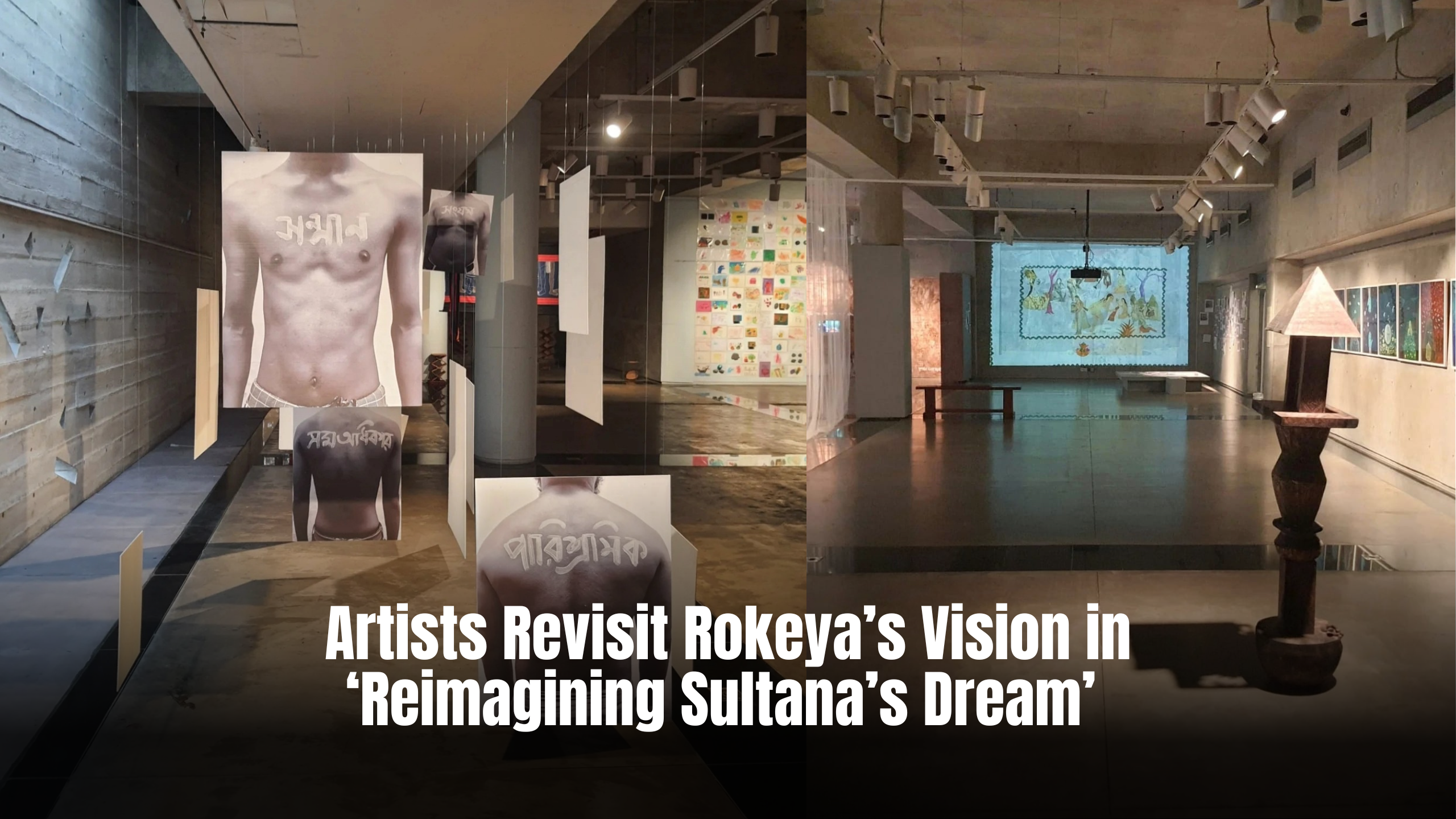

Yet, as visitors move through this exhibition’s sprawling installations, photographs, textiles, videos, and conceptual works, one realizes that the distance between Rokeya’s dream and contemporary reality remains narrower than it should be—and far more troubling than we might like to admit.

The exhibition’s strength lies in its multiplicity of voices, and together, the artworks blur the boundary between literary homage and contemporary social critique. The artists visualized women’s invisible labor, persistent structural discrimination, and the resilience forged through everyday struggle.

Many installations dwell on domesticity, wage inequality, bodily autonomy, and the silent endurance that sustains both households and economies. They do not romanticize womanhood; instead, they interrogate how patriarchy shapes aspiration, opportunity, and even imagination.

For example, a striking, suspended photographic installation that features suspended images of men, where words such as “violence,” “wages,” “women’s labor,” and “possibility” are inscribed on their bodies. The images hang from the ceiling like a suspended interrogation. Are all these accusations aimed at men, women, or society at large?

The artist framed the artwork as a question: “Perhaps you are the hunter, or the hunted.” This ambiguity implicates the audience to confront their position within systems of power. Another installation draws on Chakma weaving traditions—offering a reminder that alternative models of gender coexistence have long existed within South Asia’s indigenous cultures.

The artwork gently counters the assumption that patriarchy is universal and immutable, proposing instead that social arrangements are historical choices—capable of being rewritten. Nearby, another artwork evokes the emotional terrain of women whose dreams remain pressed beneath social expectation, while another artwork centers working-class women, pairing video art with written testimonies that echo fatigue, hope, and perseverance.

Rather than presenting women as abstract symbols, the piece insists on specificity—on listening closely to lived experience. Similarly, another installation uses repetition of sound to halt the visitor mid-step, demanding attention to voices often ignored.

Collectively, all the artworks from the 20 artists reveal a paradox. While Sultana’s Dream envisioned a radical overturning of patriarchal norms, today’s artists find themselves still grappling with remarkably similar realities. The exhibition suggests that Rokeya’s satire was not merely ahead of its time—it remains unfinished business.

But the show does more than just honor the feminist legacy; it questions its limits. Can art about women’s struggle transcend gallery walls and urban cultural circles? Or does it risk becoming another enclosed space where pain is aestheticized rather than transformed?

In this exhibition, women’s voices, bodies, protests, and questions take on material form—etched in fabric, projected on walls, suspended in midair; it does not offer easy resolutions; instead, it insists that Rokeya’s dream must be reread, revised, and challenged continuously as an evolving dialogue.

Ultimately, the exhibition reminds us that Begum Rokeya’s feminist utopia is not a destination but a process—one that requires vigilance, critique, and collective imagination. She dreamed of a world liberated from gendered injustice. So the exhibition asks a harder, more urgent question: are we any closer to living in it?

Written by Shahbaz Nahian