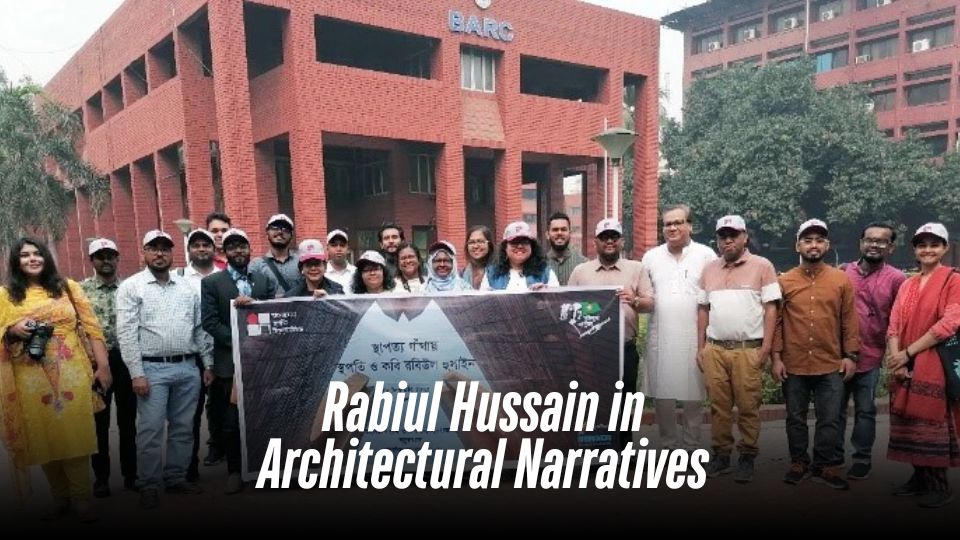

On February 28, 2025 Bangladesh Institute of Architects (IAB) and the Bangladesh Liberation War Museum organized a day-long program to tribute architect Rabiul Hussain through visiting 3 of his projects-

Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council (BARC),

Jalladkhana Killing Ground and Jahangirnagar University.

and taking a vow to protect the diversified works of the architect.

Architect Rabiul Hussain (January 31, 1943 – November 26, 2019) was a prominent Bangladeshi architect, poet, art critic, short story writer, essayist, and cultural activist. A person of multifaceted talent, honored by the Government of Bangladesh with the Ekushey Padak for his contributions to language and literature in 2018, received the Bangla Academy Literary Award for his contributions to poetry in 2009, and the Bangladesh Institute of Architects (IAB) awarded him the Gold Medal for his outstanding contribution to architecture in 2016.

He served four times as the President of the Bangladesh Institute of Architects, Vice-Chairman of the Architects Regional Council of Asia (ARCASIA), Vice-President of the Commonwealth Association of Architects, and President of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation of Architects. In addition, he was a trustee of the Liberation War Museum, an executive member of the 1971 Ghatok Dalal Nirmul Committee (Committee for Elimination of Martyrs’ Assassination), and made significant contributions to the preservation of the memories of the Independent War of Bangladesh.

Although he was born in the village of Ratidanga in Shailkupa Upazila, Jhenaidah District, he completed his secondary and higher secondary education in Kushtia District. Later, in 1968, he earned his Bachelor degree in architecture from the then East Pakistan University of Engineering (now Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology).

After obtaining the graduation, he began his professional career as an architect working with architect Mazharul Islam and later joined Shahidullah Associates. Alongside his architectural practice, he also maintained a strong passion for writing. Throughout his career, he served as a life member of the Bangla Academy, and was involved in various organizations, including the Central Kachi-Kachhar Mela (a children’s and youth organization), the National Poetry Council, the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Memorial Museum, the International Film Critic Association of Bangladesh, and the Bangladesh Institute of Architects.

Notable buildings designed by him include the Jalladkhana(Execution House), the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council building, the entrance gate of Dhaka University, the Liberation and Independence Arch, the Jahangirnagar University gate, the Bhashani Hall, the Bangabandhu Hall, the Sheikh Hasina Hall, the Khaleda Zia Hall, the Wazed Mia Science Complex, the auditorium and academic building complex of Chittagong University, and alongside architect Mazharul Islam, the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute in Gazipur, Haji Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University in Dinajpur, and polytechnic institutes in Chittagong and Khulna, among others.

Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council (BARC)

The Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council (BARC) was established in 1973 with the aim of conducting agricultural research and coordinating various related institutions in Bangladesh. Almost a decade after its founding, in 1982, architect Rabiul Hussain designed its current building. The design process, which began in 1978, spanned nearly four years.

In a remarkable way, he crafted a unique architectural design using red brick masonry that harmonized with Bangladesh’s climate, nature, and way of life. This building is a symbol of post-independence architecture, reflecting a search for an architectural style; that is free from the burden of colonization in a newly liberated land. Each detail of the building echoes the same vision. The regional architectural influence of Maestro Mazharul Islam, the pioneer of Bangladesh’s regional architecture, is evident in the design, which he was fortunate to experience starting from his third year of architectural education.

The building, located on a site shaped like the letter ‘L’ in the English alphabet, is easily noticeable among surrounding roads and structures. It stands at the junction of Airport Road and Khamar Bari Road, near Farmgate and Bijoy Sarani. The design symbolizes various aspects of aesthetic gravity, marking an early effort in the evolution of post-independence Bangladeshi architecture and the search for a Bengali “identity” in the country’s-built environment.

The location of the building, near the capital’s main international airport at Tejgaon, limited the building’s height to four floors. The rectangular building, measuring 223 feet in length and 63 feet in width, has a total built-up area of 32,700 square feet. It is aligned along the east-west axis and is equipped with optimal provisions for cross-ventilation and prevailing south winds. The three-story building is vertically divided into three functional zones. The first floor is allocated for administrative offices; the second floor houses the executive branch. The third floor features a 7,500-square-foot conference room with seating for 280 people at its center, along with a 1,350-square-foot library and a meeting room. The first and second floors are organized along a double-loaded corridor, with two staircases at the eastern and western ends of the building.

In harmony with local traditions, the roof was projected to protect the building from torrential rain and scorching sun. The BARC building essentially consists of two parts: one is the brick-clad inner shell that spans the main area, while the additional levels moderate the harsh tropical sun and protect the building during the monsoon season. Architect Mazharul Islam’s office- Vastukalabid was a key influence in experimenting with such a critical combination of climate consideration and modernist aesthetics along with that of brick mason for architect Rabiul Hussain and many young architects in the early 1970s. To give an example, his designs, including the National Institute of Public Administration (1964), encouraged a generation of architects to explore “critical regionalism” through a lens that considered climatic aspects in the visual language of architecture.

Since stone is rare and fired bricks can be produced in abundance from local clay, architects saw bricks as an unprecedented symbolic representation of the delta and its culture. Representing the soil of the riverine country, bricks were the purest or most organic building material believed by the Bangladeshi architects. The “poetry” of bricks is hard to miss in the concept and construction of the BARC headquarters building. Also, the influence of the brilliant brickwork of the Parliament Complex is palpable. Echoing the brickwork of the Philadelphia architect’s hostel for members of Parliament, architect Rabiul Hussain envisioned brick as the module for his BARC design. Bricks are used as extensively as possible in external and internal walls, columns, beams, floors, roofs, and stairs.

The essential characteristics of brick are not only reflected in the building but its proportions also seem to have originated from the brick itself. A distinguished poet, Rabiul Hussain was both the architect and sculptor of this brick building.

At times, the building’s “presence” seems more focused on the exterior than the interior. This can be felt after visitors enter the headquarters from the covered carport at the eastern end. Despite its linear monotony, the long corridor admits or reflects very little natural light, often requiring artificial lighting even during the day. The chiaroscuro effect inside evokes the image of a Hindu temple rather than an administrative office or research facility. Nevertheless, when considered within the historical context of Bangladesh in the late 1970s, the significance of this building becomes clearer. It may appear that, at times, the pursuit of an indigenous architectural expression through materiality took precedence over the internal organization.

A closer view of the BARC headquarters reveals how the building addressed the region’s climatic needs through an archaeologically consistent spatial modulation. It would not be far-fetched to see the building’s design as a reinvention of a single-row or perimetral colonnade, like a Buddhist Vihara (monastery) or the Greek temple Parthenon. The geometrically pure brick structure blends with its lush green surroundings, making the regional taste of the BARC headquarters somewhat ambiguous. Still, the building presents a kind of Bengali aesthetic identity that aligns with a universal sense of beauty. This is precisely what architect Rabiul Hussain sought in the tumultuous 1970s.

Jalladkhana Killing Ground

The Jalladkhana Killing Ground or Pump House Killing Ground, located in Mirpur-10, Dhaka, is one of the largest killing fields in Bangladesh. During the War of Independence in 1971, the areas in Mirpur predominantly inhabited by Biharis were turned into killing fields. During this time, Bengalis were brutally slaughtered by the Pakistani invading army, along with their local collaborators — Biharis, Razakars, Al-Badr, and Al-Shams — who, with the help of trained executioners, would decapitate the victims and dump them into large safety tanks.

From this killing ground, 70 skulls, 5,392 bone fragments, various items of clothing such as girls’ saris, frocks, scarves, jewelry, shoes, prayer beads, and other personal belongings of the martyrs were recovered. These remains are a stark reminder of the atrocities committed during the war and serve as a testament to the resilience of the victims and the history of Bangladesh’s struggle for independence.

In 1998, the then government launched a project to identify and renovate the country’s killing fields. On November 15, 1999, with the assistance of the 46th Independent Infantry Brigade of the Bangladesh Army, the Liberation War Museum conducted excavation work at two sites in Mirpur and uncovered two killing fields. Later, four killing fields in total were identified across the entire Mirpur area, including these two.

In 2008, the government resumed the Jalladkhana initiative, and under the overall design of architect and poet Rabiul Hussain, a memorial was created at the Jalladkhana Killing Field by the efforts of the Liberation War Museum. On the eastern side of the memorial is a sculpture titled “Jeevan Abinashwar” (Immortal Life), a joint creation by artists Rafiqun Nabi and Muniruzzaman, made from terracotta bricks and iron. This monument was officially opened on June 21, 2007.

Jahangirnagar University

Architect Rabiul Hussain designed several iconic structures, including the Jahangirnagar University Gate, Vasani Hall, Bangabandhu Hall, Sheikh Hasina Hall, Khaleda Zia Hall, and the Wazed Mia Science Complex. Among his most well-known architectural creations is the Shaheed Minar (Martyrs’ Monument) on the campus of Jahangirnagar University.

As an architect, Rabiul Hussain primarily utilized brick in his designs. The Language Movement of 1952 remains a significant source of inspiration in Bangladesh’s national history, and the movement played a crucial role in the country’s aspirations for political independence. These aspirations culminated in the bloody 1971 Liberation War. The design of the central Shaheed Minar at Jahangirnagar University was an attempt to enshrine the important milestones of Bangladesh’s national history with dignity.

The foundation of the monument is designed with a diameter of 52 feet, symbolizing the year 1952, the base for all future achievements. To honor the unforgettable dignity of 1971, the three soaring pillars rising from the base are 71 feet high. The eight steps leading up to the base symbolize the eight significant years of Bangladesh’s freedom movements post-partition: 1947, 1952, 1954, 1962, 1966, 1969, 1970, and 1971. These years are a tribute to the struggles and movements that shaped the nation. The triangular-shaped, rigid structure of the monument serves as a symbol of resilience, honoring the national heroes who fought and died for the language and the land.

The monument was inaugurated on February 13, 2008, by the then Vice-Chancellor, Professor Dr. Khondoker Mustahidur Rahman. In 1992, the Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani Hall, named after the famous political leader, was built for male students. Located to the west of the famous Bottala (a popular student hangout area) at Jahangirnagar University, this hall is positioned in front of a pond, which adds to its beauty. Due to its size, location, and the pond in front, this hall is often referred to as the “Rajbari” (palace).

The Wazed Mia Science Research Center (WMSRC) is recognized as the Center of Excellence at Jahangirnagar University, providing scientific research facilities for the university’s researchers.

Author: Fatiha Polin and Doujita Kasfi