In a large workshop, the air carries the smell of moist clay and burnt oil. Before a single bone china plate reaches the station of Morium Begum or Kamrun Nahar, it has already gone through many steps. It has been shaped by machines, fired until it is as hard as stone, and covered in liquid transparent glaze.

But in the final stage of its creation, the loud sounds of industry fade. The atmosphere becomes quiet and focused. Here, hands that know the journey from raw clay to finished vessel perform the most delicate work.

These are the hands of artisans. They guide thin, fragile decals onto smooth ceramic surfaces. Each touch is important. Each movement is a blessing on products that will travel to dinner tables around the world.

These hands belong to Morium Begum and Kamrun Nahar. They are senior workers, known as “Uchha Dakkhya”—high-skilled artisans. Their lives are deeply connected to this place. Morium has worked in the Export Decoration Department for 25 years. Kamrun has spent 22 years in Bone China Decoration. Their story is not about mass production. It is about careful, patient work and the building of a future.

“I’ve been working here for 25 years,” says Morium. Her voice carries conviction. It is more than loyalty to a job. “It doesn’t even feel like we are at a job.”

In Bangladesh, factory work is often temporary and difficult. Many workers move from one place to another, facing harsh conditions. So what makes this factory different? What unwritten promise has turned it into a home for these women for more than two decades? The answer is not only in the products they make. It is in the lives they have built through this work.

A Day’s Work: The Rhythm of the Kiln

In the wide world of ceramic manufacturing, the decoration department is special. It is where the object finds its soul. It is a major step before completion, the moment when a blank plate or cup becomes something unique. Morium and Kamrun are the guardians of this transformation. Their days follow a rhythm shaped by tens of thousands of hours of practice.

The morning begins not with machines, but with quiet preparation. They clean their stations. They arrange their tools. They prepare the raw material: stacks of ceramic ware, called “oil” in factory language. Each piece is carefully wiped to make sure the surface is flawless.

Then they turn to the decals. These are intricate designs printed on special paper. The paper is dipped in water. Slowly, the design loosens from its backing. It is ready to be transferred. This is the most delicate moment. They lift the fragile film of colour from the water and slide it onto the ceramic surface.

The placement must be perfect. The design must flow with the curves of the cup or bowl. No machine can do this. Only memory, skill, and an artist’s eye guide them. Once the decal is in place, they use a simple rubber tool. With gentle strokes, they press out every tiny air bubble and drop of water.

“The design is placed on the ware, and then a rubber tool is used to gently rub and set it,” Kamrun explains. Her hands mimic the motion. “After it’s fired, the design is permanent. It won’t even wash off.”

The final firing, called Decoration Firing Kiln (oven), makes the design indelible. The decorated pieces go back into the furnace. The heat fuses the decal into the glaze. The process is technical, demanding, and repetitive. Yet the meaning of their work goes beyond mechanics. To understand why they have given their lives to this craft, one must look at the culture of the factory.

More Than a Factory: A Foundation for Family

For Morium and Kamrun, the factory has been the backdrop of their adult lives. They entered as young women. Over time, they became matriarchs. The culture of the workplace shaped them as much as the skills they learned. It is a culture built on respect.

On the factory floor, there are no raised voices. No harsh commands. The sound is a low, cooperative murmur. This is very different from the verbal abuse that they hear is common in other industries.

“We don’t speak to anyone harshly here,” Morium says. “We don’t even raise our voices.”

This dignity is matched by flexibility. It allows them to be both workers and mothers. When their children had exams or when illness struck, they could take leave for 15 days, even a month. They did not fear losing their jobs. This security is rare.

“It’s just like a government job,” Kamrun says. “We can take a month off if we need it. You won’t get that anywhere else.”

Support is built into the system. There is a medical centre with doctors and nurses. There is a daycare for young children. But the strongest support comes from the community itself. The women call each other sisters. They share joys and sorrows.

One story shows this bond clearly. At the wedding of a cook’s daughter, workers pooled money to help with expenses. The “chairman madam” attended the celebration. Management and staff stood together. In such moments, differences of religion or background disappear. They eat together. They work together. They share goals.

This respect, flexibility, and community have created stability. It is the foundation on which Morium and Kamrun have built their lives. It is what allowed them to dream of something lasting for their children.

From Artisans to Architects of the Future

The true measure of their decades of labour is not in the countless plates and cups they have decorated. It is in the futures they are building. Their hands have shaped clay, but they have also shaped possibilities.

Morium is now the sole provider for her family. Her husband, once a worker at the same company, had to stop after a stroke. Her job became the family’s lifeline. It kept the household secure. It kept her child’s education on track.

She speaks with pride about her child, who is studying Marketing at Govt. Debendra College in Manikganj. Her dream is clear. After completing a Master’s degree, she hopes her child will join the same company in a management role. It is more than ambition. It is trust in the institution that sustained her.

Kamrun’s story is similar. Her husband left for work abroad after eight years at the company. She became the main provider for their two sons. Her income has powered their progress. Her elder son studies at Jahangirnagar University School and College. Her younger son attends a local Madrassa. For her eldest, she dreams of something big. She wants him to become a doctor. In Bangladesh, this is a difficult goal. But her belief is strong.

When asked if she truly believes she can make it happen, her answer is simple.

“I have faith,” she says.

Quiet Craft of Skilled Hands

The futures Morium and Kamrun imagine are rooted in a daily discipline that unfolds quietly inside the workshop. As the day stretches toward afternoon, the factory settles into a calmer intensity.

Rows of women remain bent over their stations, shoulders relaxed, eyes trained on surfaces that catch the light like still water. Years of repetition have shaped not just skill, but a calm authority that needs no announcement. Each movement feels assured, guided by memory rather than instruction.

For many of the women here, time inside the factory is measured differently from time outside. Seasons pass not only through festivals or family events, but through changes in production, the arrival of new designs, and the gradual shift from learner to guide. Senior workers notice this transition quietly, almost without marking the moment.

The younger workers arrive with speed and uncertainty. They soon learn that this is not a place for rushing. Precision matters more than pace. Mistakes are corrected patiently—sometimes without speech—through a demonstration, a slowed gesture, a second attempt. Knowledge moves hand to hand.

What binds these women is not only labour, but continuity. The factory floor has witnessed their youth, exhaustion, confidence, and resolve. Long after the kiln grows quiet for the day, its discipline remains etched into posture, patience, and the way they face the world beyond the gates.

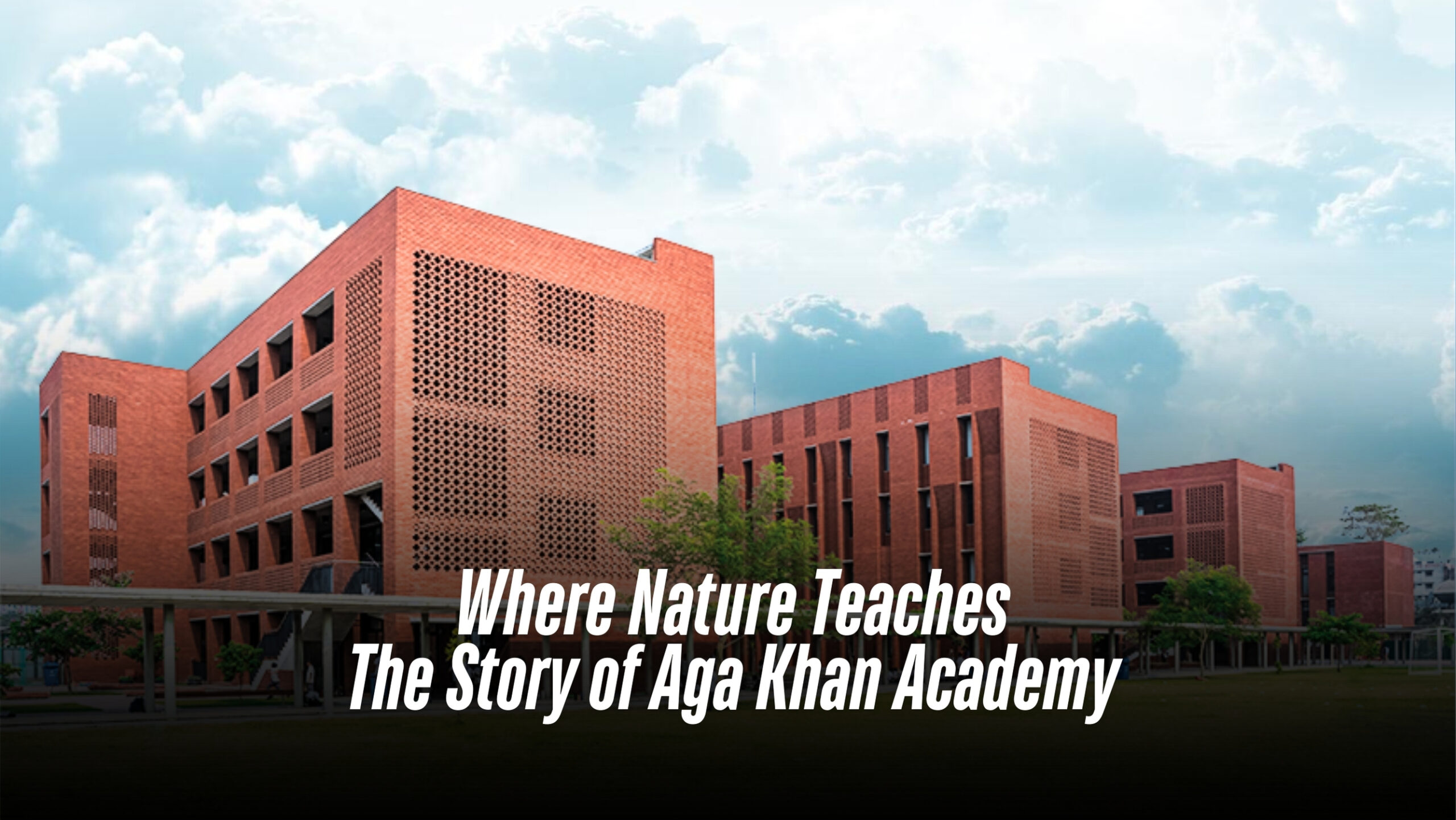

Monno, and the Weight of Time

The people mentioned in the story and the workplace where they work all belong to Monno Ceramic Industries Ltd, a name that carries weight in Bangladesh’s industrial memory. Long before ceramics became a familiar export success, Monno had already laid its foundations, shaping an industry that did not yet know its own future.

Choosing Monno as the setting for this story is not accidental. It represents the roots of Bangladesh’s ceramic sector and the human continuity behind it. Within these walls, history is not displayed—it is lived every day by workers whose steady hands carry forward a legacy shaped as much by patience as by clay.

A Legacy in Clay

Morium Begum and Kamrun Nahar are two part of the 5 lakh workforce who drive Bangladesh’s modern ceramic industry. The local market is valued at more than Tk 8,000 crore annually. But for these women, the most important numbers are their children’s graduation dates.

Their journey from beginners to high-skilled seniors is remarkable. Today, they train new employees. Morium’s story is especially striking. She is an SSC dropout. She could not finish her own schooling. Yet she is paving the way for her child’s Master’s degree.

The plates and cups they decorate will travel thousands of miles. They will sit on tables in homes far away. Few people will know the story of the hands that gave them beauty. These hands are not just tools of trade. They are instruments of hope. With each design, Morium and Kamrun lay another brick in the foundation of a better future.

Their legacy is not only in clay. It is in the lives they are building. They are matriarchs, artisans, and architects. They are sustained by quiet, unwavering belief in what is possible.

Written By Shoyeb Rehaan