An integral part of Dhaka’s image in terms of historical architecture that still remains and has been renovated and preserved is the Ahsan Manzil. And like many of common folks who grew up in Dhaka, they have always wondered, at least once in their lives, the reasons behind why this iconic landmark is painted pink. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Ahsan Manzil’s history is even more colourful. This iconic building was built on a property that has a rich history dating back to the Mughal era at the southern part of Dhaka.

An integral part of Dhaka’s image in terms of historical architecture that still remains and has been renovated and preserved is the Ahsan Manzil. And like many of common folks who grew up in Dhaka, they have always wondered, at least once in their lives, the reasons behind why this iconic landmark is painted pink. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Ahsan Manzil’s history is even more colourful. This iconic building was built on a property that has a rich history dating back to the Mughal era at the southern part of Dhaka.

During the Mughal Empire, Sheikh Enayet Ullah, Zamindar of the Jalalpur Porgona (Faridpur-Barishal), who was the original owner of the land, built a palace called Rong Mahal (which loosely translates as ‘Colourful Palace’) in 1720 for his amusement, a typical practice amongst wealthy elites at the time. He also had a garden house and a cemetery on this site. After he passed away, his son Sheikh Moti Ullah sold the property to the French traders in Bengal at the time. The new owners soon established a trading house next to the palace. Later, after being defeated in the Palashy War by the British East India Company in 1757, they had to leave their possessions behind.

After changing hands a number of times, the property was purchased by Khwaja Alimullah of Begambazar in 1830, who was a prominent merchant and an important figure of Dhaka’s Muslim community at the time. Alimullah renovated the property, turning the trading house into a residence. He also built a mosque and some other important structures in this area. After his death in 1854, his son Khwaja Abdul Ghani inherited the property and named it Ahsan Manzil after his son Khwaja Ahsanullah. He continued renovations; the old building was renamed Ondor Mohol (ladies quarters) and the new building was called Rangmahal (pleasure palace) and was later renamed Ahsan Manzil.

After changing hands a number of times, the property was purchased by Khwaja Alimullah of Begambazar in 1830, who was a prominent merchant and an important figure of Dhaka’s Muslim community at the time. Alimullah renovated the property, turning the trading house into a residence. He also built a mosque and some other important structures in this area. After his death in 1854, his son Khwaja Abdul Ghani inherited the property and named it Ahsan Manzil after his son Khwaja Ahsanullah. He continued renovations; the old building was renamed Ondor Mohol (ladies quarters) and the new building was called Rangmahal (pleasure palace) and was later renamed Ahsan Manzil.  Khwaja Abdul Ghani was one of the most influential Nawabs (Zamindar) of Dhaka. Known for his generosity and patronage of arts and culture, he expanded his estate by acquiring more lands around Ahsan Manzil and also played an important role in improving the infrastructure, education, healthcare, trade, and social welfare of Dhaka. In 1859, he built a new building on Ahsan Manzil’s property that resembled European architecture because of its domes and pillars. The Nawab named it Rangmahal and painted it with different colours every year according to his mood. On 7 April 1888, Ahsan Manzil suffered severe damage from a tornado that impacted most of its buildings, except for Rangmahal and it was temporarily abandoned. Khwaja Abdul Ghani then decided to rebuild Ahsan Manzil with more vigour and decorations than previous ones.

Khwaja Abdul Ghani was one of the most influential Nawabs (Zamindar) of Dhaka. Known for his generosity and patronage of arts and culture, he expanded his estate by acquiring more lands around Ahsan Manzil and also played an important role in improving the infrastructure, education, healthcare, trade, and social welfare of Dhaka. In 1859, he built a new building on Ahsan Manzil’s property that resembled European architecture because of its domes and pillars. The Nawab named it Rangmahal and painted it with different colours every year according to his mood. On 7 April 1888, Ahsan Manzil suffered severe damage from a tornado that impacted most of its buildings, except for Rangmahal and it was temporarily abandoned. Khwaja Abdul Ghani then decided to rebuild Ahsan Manzil with more vigour and decorations than previous ones.  He hired Martin & Co., a British construction and engineering f irm, who designed Ahsan Manzil with an Indo-Saracenic style, blended with Islamic and European elements. In 1872, the reconstruction work continued under Khwaja Abdul Ghani’s supervision, what was previously the French trading house was rebuilt as a two-storey building similar to the Rangmahal.

He hired Martin & Co., a British construction and engineering f irm, who designed Ahsan Manzil with an Indo-Saracenic style, blended with Islamic and European elements. In 1872, the reconstruction work continued under Khwaja Abdul Ghani’s supervision, what was previously the French trading house was rebuilt as a two-storey building similar to the Rangmahal.  A wooden bridge connected the first floors of the two buildings. After he died in 1896 at the age of 87 years, his son Khwaja Ahsanullah continued his father’s legacy by taking care of the palace. He added new features like electric lights, gas lamps, and water pumps as part of modernization. The palace was repaired again following the 1897 Assam earthquake. The Nawab family played crucial roles in the modernisation of the Dhaka city, particularly in the development of educational systems, healthcare, and urban infrastructure, including the f iltered water supply system that served the city population. They occupied important positions as Commissioner of Dhaka Municipality. Today, within the hyper-congested and cacophonous urban growth of Old Dhaka, it is difficult to imagine how this majestic edifice once dominated the riverfront skyline of Dhaka.

A wooden bridge connected the first floors of the two buildings. After he died in 1896 at the age of 87 years, his son Khwaja Ahsanullah continued his father’s legacy by taking care of the palace. He added new features like electric lights, gas lamps, and water pumps as part of modernization. The palace was repaired again following the 1897 Assam earthquake. The Nawab family played crucial roles in the modernisation of the Dhaka city, particularly in the development of educational systems, healthcare, and urban infrastructure, including the f iltered water supply system that served the city population. They occupied important positions as Commissioner of Dhaka Municipality. Today, within the hyper-congested and cacophonous urban growth of Old Dhaka, it is difficult to imagine how this majestic edifice once dominated the riverfront skyline of Dhaka.

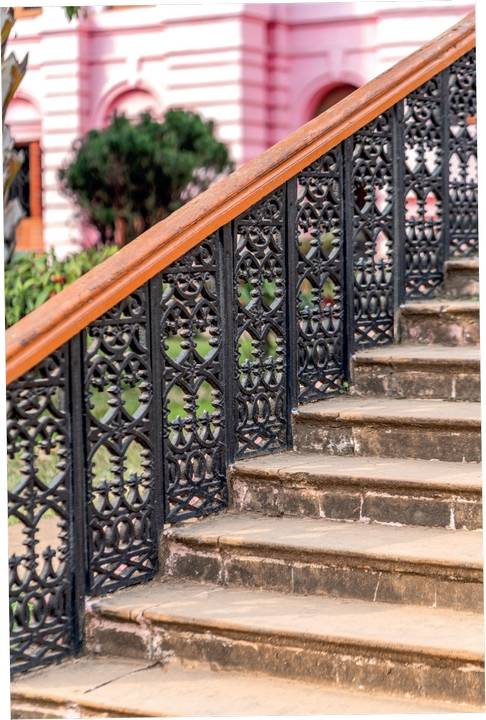

The landmark is a unique fusion of architectural styles, reflecting the rich cultural influences that shaped Bengal it over the centuries. The main palace building showcases a harmonious blend of Mughal and European architectural styles. The Mughal influence is evident in the structure’s domes, arches, and intricate decorative motifs. The ornate design of the palace’s entrance and interior chambers reflects the opulence that was characteristic of the Mughal era. European influences, on the other hand, are seen in the high ceilings, broad staircases, and expansive verandas. The palace’s central ballroom, adorned with crystal chandeliers and European-style furniture and tableware, exudes an air of sophistication that was imported from Europe during the late 19th century.

The building faces the Buriganga River and Buckland Dam. On the riverside is a stairway leading up to the 1st floor. A fountain previously sat at the foot of the stairs but was not rebuilt. Along the north and south sides of the building are verandas with open terraces. Ahsan Manzil is ostentatiously European in its architectural expression, even though the building’s recessed verandahs may recall the Mughal treatment of buildings in a tropical climate. Its triple-arched portal, Greco-Roman column capitals, pilasters, and arched windows—all suggest that it is mostly a European-style building, meshed with some decorative Indian motifs. The palace’s soaring dome appears to be more about impressing the viewer on the exterior, rather than within the interior. The dome is at the centre of the palace and is complex in its design. The room at its base is square with brickwork placed around the corners to make it circular. Squinches were added to the roof corners to give the room an octagonal shape and slant gradually to give the dome the appearance of a lotus bud. The dome’s peak is 27.13 metres (89.0 ft) tall.

The palace is divided into the eastern side, the Rangmahal, and the western side, the Andarmahal. The Rangmahal features the dome, a drawing room, a card room, a library, a state room, and two guest rooms. The Andarmahal has a ballroom, a storeroom, an assembly room, a chest room, a dining hall, a music room, and a few residential rooms. Both the drawing room and the music room have artificial vaulted ceilings. The dining and assembly rooms have white, green, and yellow ceramic tiles.

Rangmahal has 31 rooms. Now twenty three are accessible to visitors. The museum’s galleries (rooms) are displayed recreating the original environment of the palace. Step into Gallery-3, and you will see a dining hall transporting you to opulent feasts of the past. The Hall is adorned with glittering ceramic tableware.

Rangmahal has 31 rooms. Now twenty three are accessible to visitors. The museum’s galleries (rooms) are displayed recreating the original environment of the palace. Step into Gallery-3, and you will see a dining hall transporting you to opulent feasts of the past. The Hall is adorned with glittering ceramic tableware.

This architectural treasure also witnessed many historical events during the last decades of British rule in Bengal, the Pakistan period and later, of independent Bangladesh too. For example, from the last part of the 19th century to the initial years of Pakistan, the Muslim leadership of East Bengal emerged from this palace. The Nawabs of Dhaka used to conduct their court affairs here. Many political meetings were held here under the initiative of Nawab Ahsanullah (1846-1901), who was a firm believer in Muslim separate identity. Almost all the Viceroys, Governors and Lieutenant Governors of British India who visited Dhaka at the time, spent time at the Ahsan Manzil. On February 18-19, 1904 Viceroy Lord George Nathaniel Curzon visited East Bengal to form public opinion in favour of Bengal division and stayed as a guest of Nawab Salimullah at Ahsan Manzil. It was decided to establish the All India Muslim League in a meeting held Ahsan Manzil in 1906 after the partition of Bengal in 1905.

On February 18-19, 1904 Viceroy Lord George Nathaniel Curzon visited East Bengal to form public opinion in favour of Bengal division and stayed as a guest of Nawab Salimullah at Ahsan Manzil. It was decided to establish the All India Muslim League in a meeting held Ahsan Manzil in 1906 after the partition of Bengal in 1905.

Ahsan Manzil still stands as a testament to the opulence and grandeur of a bygone era. This architectural marvel has been witnessed to the ebb and flow of history, serving as a symbol of power, prestige, and resilience. The government of Bangladesh acquired the palace and property in 1985 and began renovating it, taking care to preserve the remaining structure. Renovations were completed in 1992 and ownership was transferred to the Bangladesh National Museum. Part of the northern side of the property was given to the Dhaka City Corporation while half of the Andarmahal and the Nawab residential area were beyond acquisition.

Ahsan Manzil was opened to the public as a museum in 1992. Today, Ahsan Manzil houses a treasure trove of artifacts, documents, and memorabilia that encapsulate the diverse chapters of its history, offering visitors a glimpse into the past and its significance that goes far beyond than being just a tourist attraction. In terms of tourism, Ahsan Manzil draws in both local and international tourists who are eager to immerse themselves in Dhaka’s once rich history and aesthetic grandeur. This flocking of visitors also contributed to the local economy.  It has spurred the growth of various types of businesses in the vicinity (especially food), and created employment opportunities. The palace is a living testament to the importance of preserving cultural heritage, especially in the reality of Bangladesh where significant structures of heritage are still being demolished in the name of so-called development or personal purposes.

It has spurred the growth of various types of businesses in the vicinity (especially food), and created employment opportunities. The palace is a living testament to the importance of preserving cultural heritage, especially in the reality of Bangladesh where significant structures of heritage are still being demolished in the name of so-called development or personal purposes.

Ahsan Manzil is not merely a building or a ordinary building; it is a living chronicle of Bangladesh’s past, present, and future. There was not a single building in Dhaka as impressive as Ahsan Manzil. Its dome was the highest tower of the town, attracting people from near and far. When move from one room to another, the ambiance brings back the tales of the nawabs of Dhaka and their luxurious lives.

The palace now showcases 3,831 historical artefacts. Galleries of Ahsan Manzil museum highlight the nawabs’ forward-thinking roles in Dhaka’s development. Ahsan Manzil is not merely a building or a ordinary building; it is a living chronicle of Bangladesh’s past, present, and future. There was not a single building in Dhaka as impressive as Ahsan Manzil. Its dome was the highest tower of the town, attracting people from near and far. When move from one room to another, the ambiance brings back the tales of the nawabs of Dhaka and their luxurious lives. Its architecture is a testament to the cultural diversity that has enriched the nation’s heritage. Its history is a tapestry of opulence, neglect, restoration, and rebirth. The Pink Palace, with its storied past and architectural splendor, invites all to step into its hallowed halls and become a part of its ongoing narrative, where history and culture intertwine to create a lasting legacy for generations to come.

The palace now showcases 3,831 historical artefacts. Galleries of Ahsan Manzil museum highlight the nawabs’ forward-thinking roles in Dhaka’s development. Ahsan Manzil is not merely a building or a ordinary building; it is a living chronicle of Bangladesh’s past, present, and future. There was not a single building in Dhaka as impressive as Ahsan Manzil. Its dome was the highest tower of the town, attracting people from near and far. When move from one room to another, the ambiance brings back the tales of the nawabs of Dhaka and their luxurious lives. Its architecture is a testament to the cultural diversity that has enriched the nation’s heritage. Its history is a tapestry of opulence, neglect, restoration, and rebirth. The Pink Palace, with its storied past and architectural splendor, invites all to step into its hallowed halls and become a part of its ongoing narrative, where history and culture intertwine to create a lasting legacy for generations to come.

Written by Shahbaz Nahian