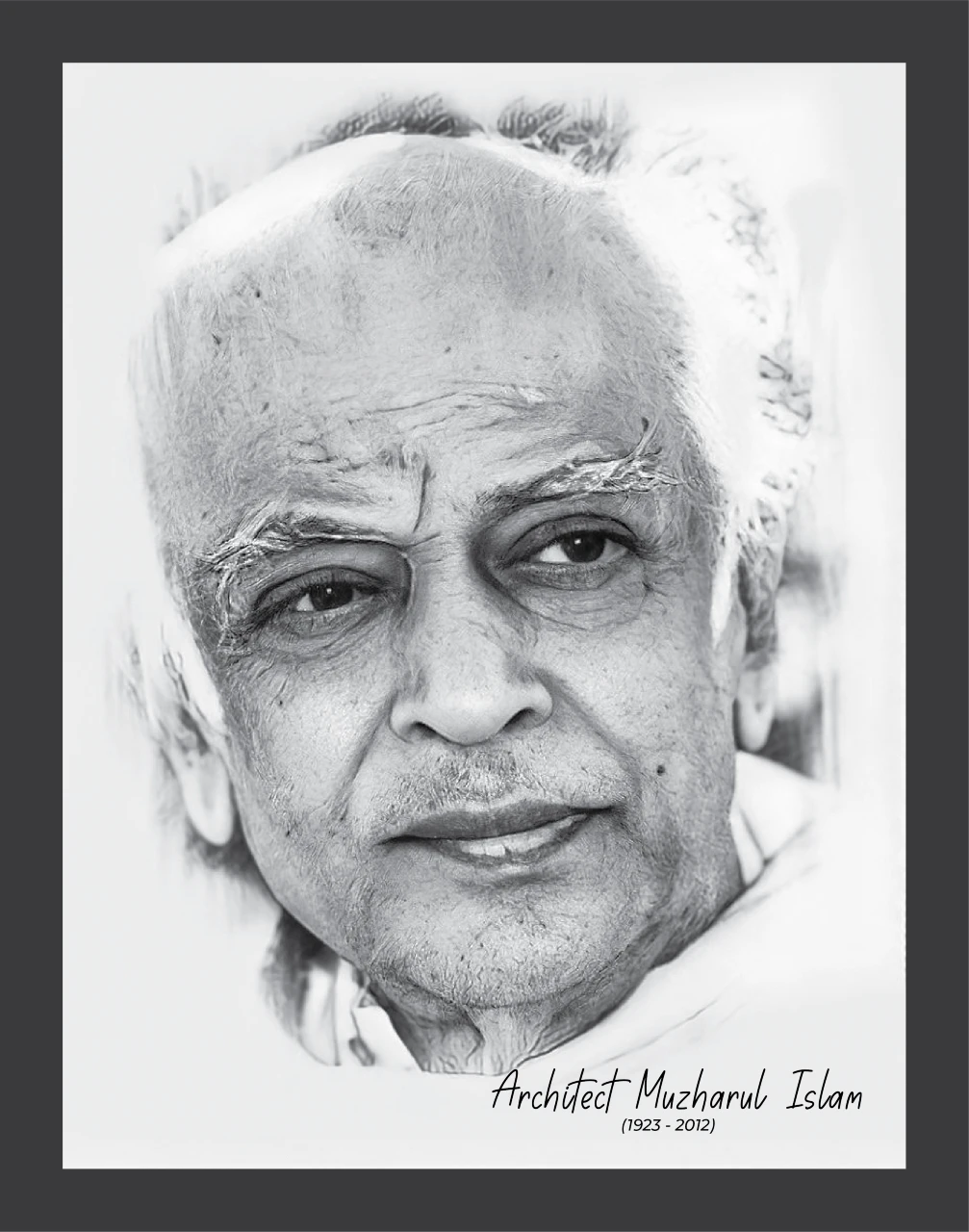

Beyond his role as an innovative architect, Muzharul Islam was characterised by humility and an unassuming nature. His consistent choice of traditional clothing and a preference for a modest lifestyle indicated a deep commitment to his craft rather than a pursuit of personal recognition. The simplicity and focus on perfection in his work underscored the profound impact of his architectural contributions, and the enduring prominence of his legacy in South Asian architecture speaks volumes about his unwavering dedication and passion. The roots of modernism in Bengal can be traced back to the Bengal Renaissance, a cultural and intellectual movement spanning the late 18th to early 20th centuries. This period witnessed a resurgence of liberal thoughts, intellectual exploration, and a reevaluation of traditional norms. The Bengal Renaissance played a pivotal role in reshaping ideas related to liberalism and modernity. During the British colonial rule, neo-classical and neo-gothic aesthetics significantly influenced East Bengal’s architecture, evident later on in East Pakistan in public structures symbolising power, the rule of law, and cultural dominance. Before the 1971 War of Independence, which resulted in the formation of Bangladesh, East Pakistan sought to establish itself as a liberal community. One significant architecture during this period was the Faculty of Fine Arts, which emerged as a modern marvel. This architectural endeavour intentionally steered clear of ornamental elements associated with Mughal or Indo-Saracenic styles.

Muzharul Islam, the architect behind this significant structure, employed a conscious strategy in abstracting his design through a modernist visual expression. This deliberate approach aimed to rid the architecture of perceived political associations with instrumental religion. By steering clear of traditional and ornamental influences, he aimed to create a design that stood as a manifestation of secular ideals, distancing itself from the religiously charged politics that defined the era.

In doing so, the Faculty of Fine Arts became more than just a physical structure; it became a visual and ideological statement, symbolising the pursuit of a secular and liberal identity for East Pakistan through its architecture.

Indeed, Mr. Muzharul Islam’s influence extends far beyond his time, establishing him as the one of the most influential architects in the history of his country. His visionary contributions to architecture, coupled with his dedication to shaping the national identity through his work, have left an indelible mark.

In 1964, at the pinnacle of his career, Muzharul Islam established the architectural consulting firm “Bastukolabid”. It marked a milestone, as it was the first architectural consulting firm in the East Pakistan. At that juncture, one who could have done his work solely for personal profit, he expressed the desire for collaboration with world-class architects. That period witnessed the notable involvement of the American trio — Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, and Stanley Tigerman — in architectural endeavours in Bangladesh. Muzharul Islam played a pivotal role in fostering this collaboration, recognising the need for visually and intellectually stimulating paradigms in the Bengali context.

The partnership brought a global perspective to the architectural landscape and contributed to the enrichment of architectural discourse and innovation in this region. Muzharul Islam’s visionary dream was to elevate Bangladesh into a developed, alluring, and civilized nation through meticulous physical planning and control over every square foot of its territory. He aimed to craft a distinctive national identity that would set Bangladesh apart.

Muzharul Islam, a fervent patriot who not only fought on the battlefield during the 1971 War of Independence but also contributed significantly to shaping the national identity through his endeavours in art and architecture, faced a disheartening period of neglect in the post-independent era.

Following Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, Muzharul Islam found himself marginalised from government projects, a stark departure from his active role in the liberation movement. The reasons behind his sidelining were multifaceted, with a prominent factor being his steadfast commitment to Marxist and Leninist principles. This ideological stance placed him at odds with the establishments during that period.

Despite his noteworthy contributions to the freedom of Bangladesh, Muzharul Islam experienced discord with the post-independence political landscape. This period of neglect serves as a poignant illustration of the complexities and challenges faced by individuals with unwavering ideologies in the aftermath of political transitions.

In 1953, at the age of 30, Muzharul Islam designed the Institute of Arts and Crafts (Art College) building in Dhaka. It is recognised as the first modern building in Bangladesh. After completing the Fine Arts Building in 1956 and the National Library in 1958, it was being said that Muzharul Islam wanted to include other arts like music building, dance, and dramatics departments in addition to the architecture school besides the Fine Arts Building. Creating a total art complex would have expanded the scope of architectural education, breaking away from the traditional notion that architecture is solely rooted in science.

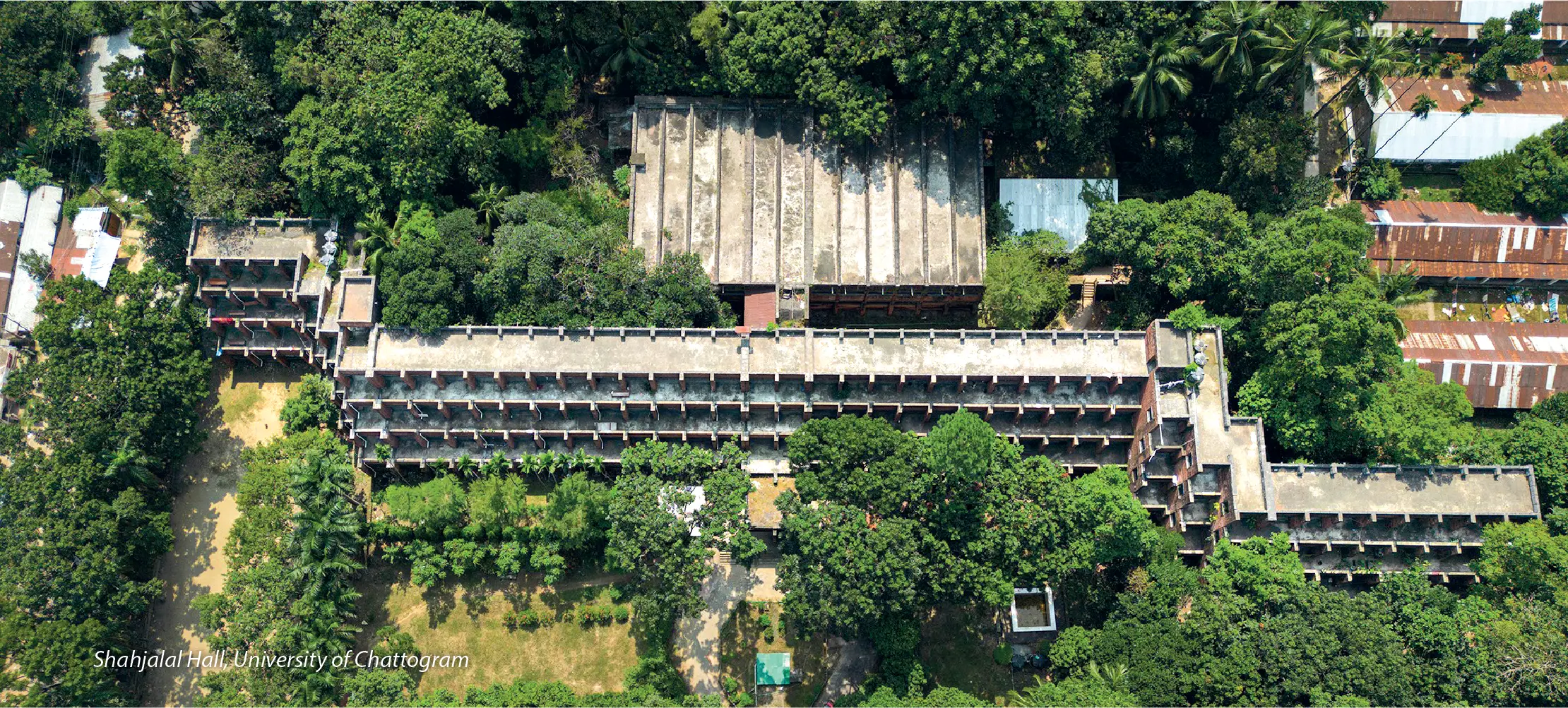

If Muzharul Islam had succeeded in implementing his vision, it could have had a profound impact on architectural education in the country. The inclusion of diverse art forms within the same educational campus might have fostered creativity, collaboration, and a broader understanding of the cultural and aesthetic aspects of architecture. This holistic approach could have produced architects with a richer skill set, capable of not only designing structurally sound buildings but also creating spaces that resonate with cultural and artistic expression. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Muzharul Islam’s Six-B pencil and charcoal inspired designs like Falgudhara, building one modern architecture after another. Science Laboratory (BCSIR) building in Dhaka, NIPA Bhawan of Dhaka University, BADC Bhawan and Jiban Bima Bhawan in Motijheel, Rangamati Township, Chittagong University, Jahangirnagar University, the World Bank Dhaka Office, Mausoleum of National Poet Kazi Nazrul Islam etc. are modern architectures used as a tool to build a modern society. His most important work was born when the Governor’s Conference of Pakistan decided in 1959, under the President Ayub Khan, that Dhaka will be the second capital of Pakistan. The government decided to build a capital complex at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka. Muzharul Islam was given to design Jatiyo Sangsad Bhaban (National Assembly Building of Bangladesh). But, he brought his teacher Louis I. Kahn into the project to do a significant work for future generation. Islam worked closely with him from 1965 until Kahn’s death in 1973.

Muzharul Islam was deeply committed to truth and beauty, not just in architecture but also in every aspect of his life. The influence of Marxist and Leninist principles suggests that Muzharul Islam approached his work with a sense of social responsibility and a commitment to addressing issues of exploitation and disparity. This perspective aligns with his belief in freedom from exploitation, emphasising the importance of creating a built environment that serves the needs of society and contributes to the enlightenment of the community. He set out on a mission to create beauty after drawing inspiration from the Bengal Renaissance and Rabindranath Tagore’s wisdom. His goal was to help shape a unique identity for an evolving Bangladesh. A quintessential Bengali, humanitarian, politically aware, culturally minded architect, Muzharul Islam will be remembered forever for his dedicated, creative and noble contribution to the architectural history of Bangladesh.

Written by Samia Sharmin Biva