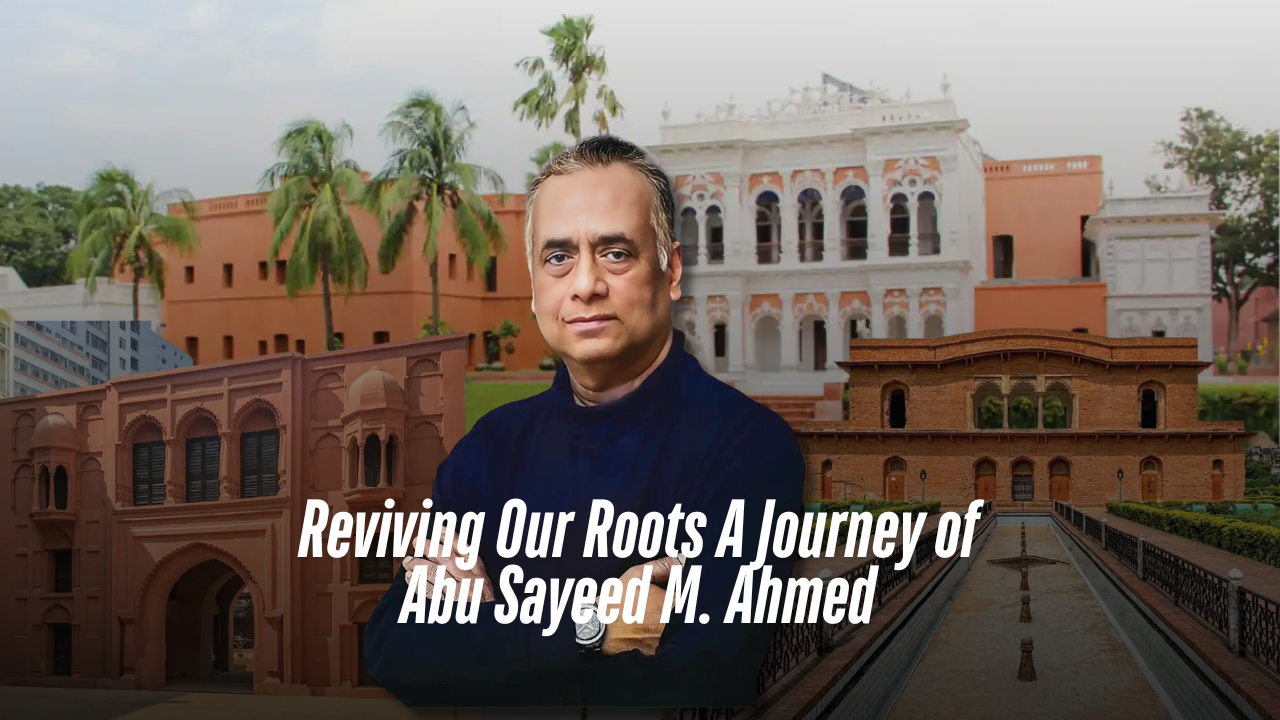

While many architects push the boundaries of innovation, there have been some who charted a different course. Instead of focusing solely on creating the new, Architect Dr. Abu Sayeed M. Ahmed turned his gaze to the past—reviving forgotten monuments and ancient buildings. A pioneer in conservation architecture, he has dedicated his life to protecting and restoring the architectural jewels of Bangladesh. For Dr. Sayeed, preserving heritage is not just about safeguarding structures; it’s about understanding who we are and how the past shapes our identity today.

From restoring historic mosques and colonial buildings to leading the Institute of Architects Bangladesh as president thrice in a row and serving as the elected president of ARCASIA on an international level, his contributions have earned him both national and global recognition. As an educator and author, his efforts in heritage protection continue to inspire future generations of architects. Dr. Sayeed’s legacy as a guardian of Bangladesh’s architectural treasures makes him an enduring force in both the past and future of the nation’s architectural identity.

A pioneer in conservation architecture, he has dedicated his life to protecting and restoring the architectural jewels of Bangladesh. For Dr. Sayeed, preserving heritage is not just about safeguarding structures; it’s about understanding who we are and how the past shapes our identity today.

From the Water’s Edge: A Childhood in Comilla Long before the architectural world knew his name, there was a young boy in Comilla, Bangladesh, who spent his days by the waterside, watching the reflections of ancient trees shimmer in the lights and ponds. In this quaint town, the city’s water bodies—like Dharmasagar and Rani’s Dighi—were more than mere landmarks; they were playgrounds, gathering spots, and the backdrop to countless moments of childhood joy. Football games often ended with a refreshing dip in the cool waters, and laughter echoed across the banks, blending with the gentle sounds of nature. That little boy, Abu Sayeed M. Ahmed, found joy in simple things like drawing intricate sketches, building models, and creating Eid cards. His love for the technical precision of his creations grew in the quiet corners of his home and school, unknowingly laying the foundation of his future as an architect.

Abu Sayeed’s fascination with design was nurtured by his father, Abdur Rashid, a principled educator, and his mother, Helena Begum, whose warmth and love kept the heart of their home alive. The roots of his curiosity about history and architecture grew deep in the soil of Comilla, where he first learned to see beauty in the details around him. Even as a student at Comilla Zilla School and later Comilla Victoria College, Sayeed stood out. His involvement in Scouting allowed him to explore Bangladesh’s landscapes, meet people from different walks of life, and develop a strong sense of leadership. By the time he graduated in 1976, these experiences had shaped his collaborative spirit and a love for discovery—qualities that would define his career for years to come.

His bond with his architecture batchmates was legendary. Known as the “batch of talents,” they shared a camaraderie that extended beyond classrooms. From organizing grand tours across India and Bangladesh to planning picnics, Sayeed often emerged as the natural leader. His ability to bring people together flourished during these years, and the friendships he built remain strong to this day. In 1983, he graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture, ready to leave his mark on the world.

Stepping Into a New World: The BUET Years In 1976, Abu Sayeed entered BUET’s Department of Architecture, a choice that marked the beginning of a transformative chapter. Life at BUET was unlike anything he had known. Sharing dormitories with students from other disciplines introduced him to diverse perspectives. While his engineering peers were deep in equations, Sayeed and his classmates were sketching, brainstorming, and working late into the night on design projects.

The Architect Emerges: Early Projects at ECBL

Sayeed’s first professional step was joining the consultancy firm ECBL, where he worked for four years. It was a period of intense learning and growth. He became involved in landmark projects such as the Bangabandhu Hall of Dhaka University, Nagar Bhaban, the Air Force Academy in Jessore, and the Dhaka Cantonment’s central mosque and library. These projects gave him firsthand experience in balancing design with functionality. His natural f lair for leadership and meticulous approach to detail made him an asset to the firm. However, Sayeed knew his journey was far from over—he dreamed of exploring new horizons.

A New Chapter in Germany: Rediscovering Bangladesh

In pursuit of higher education, Abu Sayeed M. Ahmed embarked on a bold journey to Germany to pursue his master’s degree in architecture. Before leaving, he received two meaningful gifts—one from Lailun Nahar Ikram, the Managing Director of ECBL, who gifted him $1,000, and another from Prof. Abu Haider Imam Uddin, a colleague at ECBL, who presented him with the book Islamic Heritage of Bangladesh by Dr. Enamul Haque. Little did he know, this book would become a faithful companion in his new chapter abroad. The transition was anything but easy. Sayeed had to learn German from scratch, adapt to a foreign culture, and navigate a competitive academic environment. He lived in a hostel with students from all over the world, and conversations inevitably turned to his homeland. “What makes your country special?” his peers would ask. At first, Sayeed found himself at a loss for words, unsure of how to convey the richness of Bangladesh’s heritage.

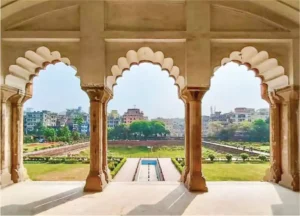

But then, the book he had been gifted came to his mind. The book Islamic Heritage of Bangladesh became his bridge to the world. He started to share Bangladesh’s architectural treasures—the Sixty Dome Mosque, the Small Sona Mosque, then the Paharpur Monastery, Mahasthangarh, and so on. His peers were astounded. “Bangladesh has a heritage this rich?” they asked, their eyes wide with surprise. They had never imagined that such ancient, awe-inspiring architecture existed in a country they often perceived as impoverished. These moments sparked something profound in Sayeed. He realized how these architectural marvels were not just buildings; they were symbols of a long-forgotten history that connected the people of Bangladesh to their past, their culture, and their identity. What began as an academic pursuit to build structures evolved into a deep fascination with history and heritage. During his master’s program at the University of Karlsruhe, Sayeed wrote a paper on Islamic architecture in Bangladesh, a project that would later open the door to a Ph.D. opportunity in restoration and conservation—his true calling. This new journey not only shaped his career but also solidified his commitment to preserving the past, a passion that would define the rest of his life.

The Calling: Returning to Bangladesh

After completing his Ph.D., Abu Sayeed returned to Bangladesh. Amid debates over architectural education and faculty resignations at BUET, he joined the newly established Department of Architecture at the University of Asia Pacific. But teaching wasn’t enough. Sayeed wanted to bring the past back to life, to preserve the heritage he had grown so passionate about. As a teacher, he shaped future architects, balancing academics with active contributions to restoration projects.

Reviving the Past: Restoration Journey

Dr. Abu Sayeed Mostaque Ahmed embarked on the monumental task of restoring the centuries-old Nimtali Deuri, an iconic gateway that once marked the entrance to the grand Nimtali Kuthi palace in Dhaka. This landmark project, initiated in 2008, became his first major heritage conservation endeavor in Bangladesh. After extensive research and consultation, Dr. Ahmed and his team successfully restored the west gateway (Deuri), now housed within the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, preserving a crucial piece of Dhaka’s architectural history.

The restoration process was nothing short of meticulous. It began with an in-depth study of historical sketches, documents, and the architectural history of the site. Dr. Ahmed and his team conducted thorough excavations to examine the foundation and soil layers, ensuring that the restoration was both historically accurate and authentic. One of the primary challenges was recreating authentic materials like Surki (a mixture of lime and brick dust), which had been used in the original construction, as well as finding skilled artisans capable of reviving traditional craftsmanship.

Breathing New Life into History: Notable Works of Dr. Abu Sayeed Mostaque Ahmed

Dr. Abu Sayeed Mostaque Ahmed’s expertise in architectural conservation has breathed new life into Bangladesh’s most treasured landmarks, earning him recognition both nationally and internationally. His significant restoration projects include the Doleshwar Hanafia Jame Mosque in Keraniganj, which earned a UNESCO Award for Cultural Heritage; the Mughal Mosque in North Halishahar, Chittagong; and iconic sites like Mithamain Kacharibari, Burij Nawab Bari, Alfadanga, Dhaka Gate, and Hammamkhana of Lalbagh Kella. Yet, his most celebrated work remains the restoration of Bara Sardar Bari in Sonargaon—a 600-year-old structure that had long been forgotten. Under Dr. Ahmed’s leadership, the building was transformed into the National Museum of Folk Art and Crafts, revealing an earlier Muslim settlement beneath what many had mistakenly believed to be a colonial-era building. This project earned widespread acclaim from the Institute of Architects Bangladesh (IAB) and stands as a testament to the enduring relevance of the past in shaping the future. Through his tireless efforts, Dr. Abu Sayeed Mostaque Ahmed continues to preserve and restore Bangladesh’s architectural heritage, ensuring that these historic landmarks remain a living part of the country’s identity for future generations.

Preserving Heritage, Reviving Craftsmanship

Dr. Abu Sayeed Mostaque Ahmed believes that historical conservation goes beyond merely rebuilding; it’s about reviving history and safeguarding the traditional craftsmanship that originally brought these structures to life. In his restoration projects, one of the most significant outcomes was the nurturing and training of local artisans and small industries, ensuring the continuity of ancient crafts and skills.

Dr. Ahmed often refers to these artisans as his “Guru”—a term of deep respect—because they imparted invaluable knowledge and techniques that have been generations. passed through By working closely with these artisans, he was able to preserve the authenticity and cultural integrity of the heritage sites restored. For he Dr. Ahmed, preserving a building is not only about the structure but also about preserving the artistry and techniques that formed its foundation.

An Architect for Asia:

The Global Stage With the present tenure, he is a three-time elected president of the Institute of Architects Bangladesh. And his influence was not confined to Bangladesh. His vision reached far beyond, extending across the borders of Asia. As President of the Architects Regional Council of Asia (ARCASIA), he worked to bring architects from 22 countries together, sharing knowledge, ideas, and a passion for preserving the past. Under his leadership, Bangladesh hosted the 50th anniversary of ARCASIA, showcasing the country’s architectural wealth to the world. His contribution to the global architectural community was recognized when he was honored with the AIA Presidential Medal and Honorary Membership by the American Institute of Architects in 2022, acknowledging his work in fostering international collaboration and promoting heritage conservation.

A Legacy Written in Stone and Memory

Today, Dr. Abu Sayeed M Ahmed stands as a beacon of hope for anyone who believes that architecture can be more than just a series of structures. It can be a reflection of a nation’s soul, a preservation of its past, and a bridge to its future. As the Dean of the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Asia Pacific, he passes on this legacy to the next generation of architects, teaching them not only how to design buildings but also how to preserve the stories embedded in every brick. In every line he draws and in every restoration he leads, Abu Sayeed revives more than just architecture; he breathes life into history, ensuring that Bangladesh’s heritage will continue to inspire and captivate the world for generations to come.