In the crowded clusters of Dhaka’s architectural offices—where every firm spoke in bold, predetermined tones—finding an original voice was never easy. For Architect Rashed Hassan Chowdhury, the journey began not with buildings, but with books and design experiments of all kinds.

Encouraged by his elder brother to pursue architecture, he entered BUET carrying curiosity and a restless desire to make and learn. Even as a student, Rashed was never confined to one discipline.

He moved fluidly between book design, graphic work, product design—anything that allowed imagination to unfold in tangible form.

But the multiplicity of voices, the weight of tradition and pressure of trends, left him with a fundamental question: How does one discover one’s own architecture? Rashed’s answer, at least in the early years, was to do everything. His first role was as a researcher at BUET’s Green Architecture Cell, followed by a post as lecturer at the University of Asia Pacific.

After office hours, he joined architects like Nahas Khalil, Marina Tabassum, and Mahmudul Anwar Riyaad on project-based work—each collaboration sharpening instincts and broadening vocabulary.

And at night, in the chilekotha/attic of his brother’s office—with only a computer and printer—he began sketching the contours of his own practice. Sleep was rare, but happiness abundant. Eventually came the realization:

energy without direction cannot sustain itself. “I was doing too much, but none of it was really going anywhere,” Rashed recalls. That reckoning pushed him to leave the safety of multiple jobs and commit to a singular vision.

Out of that decision was born Dehsar Works—a multidisciplinary practice whose very name is simply the last-to-first spelling of “Rashed,” a gesture as honest and direct as the work it produces.

Learning by Doing

Dehsar Works is not merely an architecture office—it is a laboratory. For Rashed, design is not about formula but about process, about finding concept and clarity. “The design process excites me most. It still does, every single time,” he says. This philosophy is reflected in the kinds of projects he chooses and the way they evolve: adaptive reuse, experimentation with materials, finding beauty in imperfection, and above all, engaging with the everyday lives of users.

The Blues Communications Office, a transformation of a warehouse into a bold new workspace, tested both his patience and creativity. The design called for a complex metal structure—one that contractors hesitated to take on. Instead of abandoning the idea, Rashed and his team decided to build it themselves.

They formed a sister concern, aptly named Workshop, to execute the construction. Through trial, error, and persistence, they not only completed the project but also gained a wealth of knowledge about materials and making.

Ajo Idea Space is perhaps the purest example of his ethos. Conceived as a café and gathering space, it was never meant to be a conventional air-conditioned box. Instead, it embraced openness, natural ventilation, and a certain looseness that invited people to linger.

The pavilion-like structure, with its vaulted steel forms and porous screens, blurred the boundary between inside and outside. It embodied sustainability not as a checklist but as a lived experience: a place where people ate, conversed, and created in ways that felt organic.

Another notable work is the Beximco Learning and Development Center, a lightweight, semi-circular hall framed with steel and clad in polycarbonate sheets. Here, the emphasis was on creating an affordable, sustainable, and flexible learning environment that could anticipate future uses.

By designing with recyclability and climate responsiveness in mind, Rashed sought to redefine what corporate infrastructure could mean in Bangladesh.

Similarly, the Artistry Marble & Granite Experience Center transformed an old warehouse into a gallery-like environment for natural stones. Rather than demolish and rebuild, the design preserved and reinterpreted the existing shell, reusing nearly half the materials. The result was a spatial narrative where light and texture interacted with surfaces, allowing visitors to experience stone not as a static product but as a dynamic material.

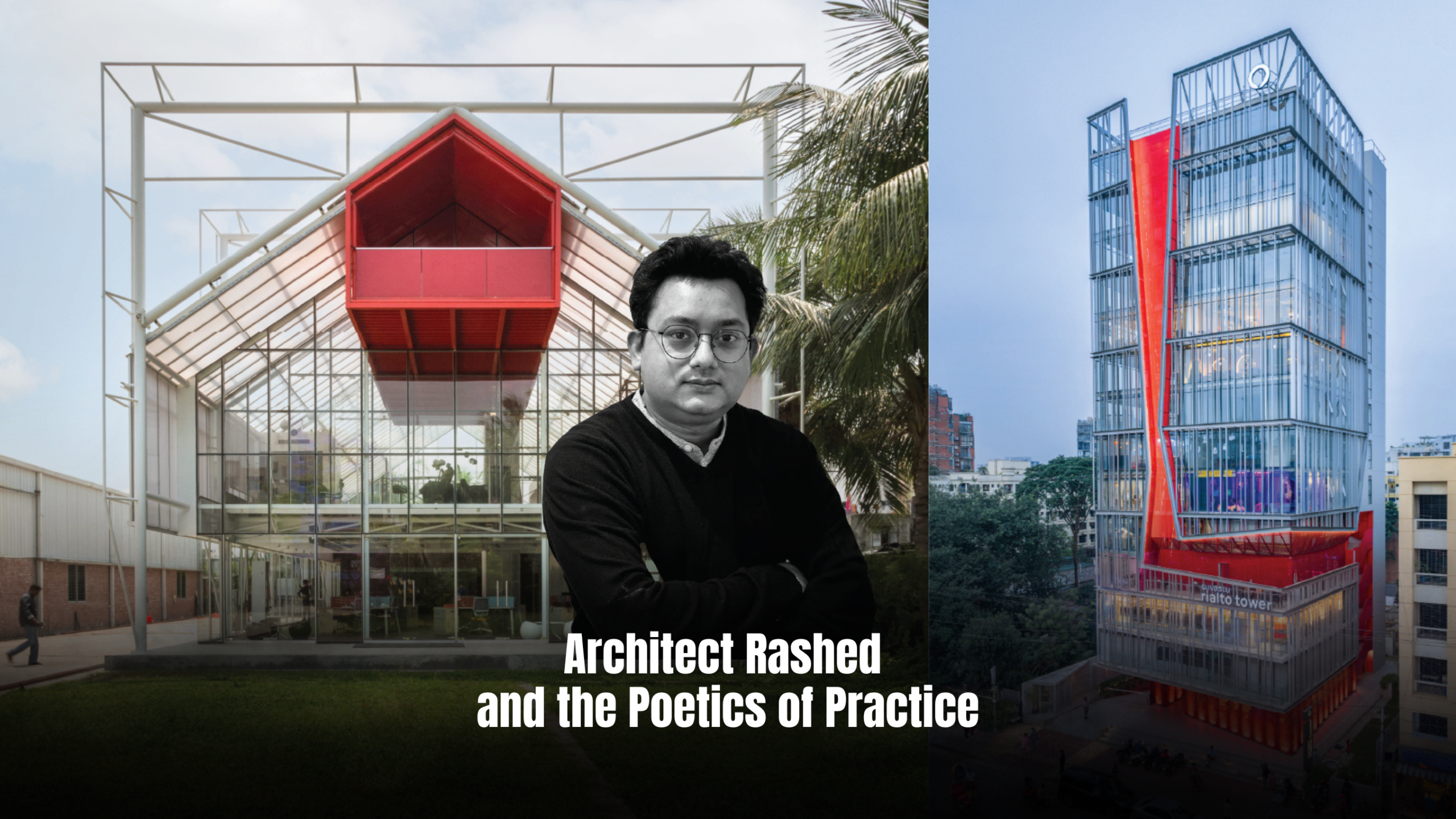

Another iconic project of Rashed is Suvastu Rialto Tower, a contemporary commercial landmark in Dhanmondi. Developed by Suvastu Properties Ltd., the project embodies functionality, visibility, and refined contemporary design.

Suvastu Rialto Tower is a 3-basement, ground plus 13-storey commercial building, developed on approximately 10 kathas of land. The vertical organization of the building efficiently accommodates parking, retail, and office functions, addressing both spatial optimization and urban density challenges.

The architectural language of Suvastu Rialto Tower is distinctly modern, characterized by clean lines, transparency, and material contrast. The façade features a glass curtain wall system, combined with aluminium elements and contemporary detailing. The glass facades not only enhance the building’s aesthetic appeal but also maximizes daylight penetration, contributing to a pleasant and productive interior environment.

A Philosophy of Effort

Rashed is not shy about offering advice to the younger generation of architects. His words are sharp but encouraging: “Stop complaining and start enhancing your skills.” For him, the profession is not merely about constructing buildings but about learning by doing—whether in furniture, graphic design, or urban experiments. Bangladesh, in his eyes, is a land of vast opportunity, waiting for those willing to work with patience and integrity.

“There is so much to do, but very few skilled people willing to put in the effort,” he says. The formal degree, while important, is not enough. Real growth, he believes, happens through curiosity, through the courage to try, to fail, and to learn.

Toward a Different Future

The story of Dehsar Works is, in many ways, the story of one architect’s relentless pursuit of authenticity. From a chilekotha room with a single computer to award-winning projects recognized internationally, the journey has been marked not just by structures built but by lessons learned.

As Rashed continues to shape spaces that are adaptive, playful, and deeply contextual, he reminds us that architecture is less about monuments and more about moments: the feel of light against stone, the gathering of people under a vaulted roof, the quiet joy of inhabiting a space that feels both surprising and familiar.

And in that pursuit—in that refusal to settle, in that ongoing process of becoming—lies the true poetry of his architecture.

Written by Fatima Nujhat Quaderi