Kromosho Beyond ‘Belonging’

In the mid-2000s, a young- Munem Wasif began exploring the hidden corridors of Old Dhaka alongside his trusty, timeworn companion, Zenit—a mechanical relic from the Soviet era. This journey eventually culminated in his 2012 photographic masterpiece Belonging, a work that revolutionized visual storytelling in Bangladesh’s art scene. Much like the dark, ever-flowing waters of the Buriganga that have witnessed Dhaka’s transformation, Wasif’s artistic journey has traversed many phases—each urging audiences to look beyond the surface. From `Seeds Shall Set Us Free’ to `Collapse’, his work continuously invites deeper reflection, all while retaining an unbreakable bond with Old Dhaka. After nearly 16 years, Munem Wasif returns to Dhaka with a solo exhibition titled `Kromosho’, now on display at Bengal Shilpalay in the capital. The show, which runs until May 31, 2025, features contributions from curatorial advisor Tanzim Wahab, project assistant Iftekhar Hassan, and architectural designer Dehsar Works, and is open to everyone. Reflecting on his previous work, Wasif explained, “I felt something was lacking when Belonging was released. It merely touched upon the surface of the people and their celebrations—I couldn’t capture the core of their daily lives, the very ‘life’ of Puran Dhaka. That realization gave birth to Kheya’l. This exhibition is a testament to my transformation over the past two decades.” The opening at Bengal Shilpalay buzzed with energy as art enthusiasts gathered to witness what promises to be one of the most memorable exhibitions in recent memory. Kromosho unfolds in three movements: it begins with Wasif’s ethereal black-and-white photographs from the Belonging era, which converse with his fresh, vibrant color works from Stereo. This juxtaposition creates a dynamic tension between past and present, memory and reality. In Kheyal, a cinematic meditation captures the pulsing rhythm of Old Dhaka, while the installations Shamanno and Paper Negative blend documentation with imagination, challenging our perceptions of what is real versus what is remembered. Critically, Old Dhaka may seem like a ticking time bomb—overcrowded, decaying, and a bitter relic of collective neglect. Yet, Wasif’s work reveals the hidden vitality amid this chaos, unearthing a poetry rarely seen by the casual observer. Kromosho does more than display images of a place; it captures its very essence. The exhibition serves as a mirror, prompting us to consider what we preserve and what we forsake in our relentless march toward modernity. In an age of rapid urbanization and cultural amnesia, Wasif’s work stands as both an archive and an elegy—an enduring reminder that some stories transcend what can be captured by cameras or words. To fully appreciate its depth, one must experience it both in person and with an open, reflective heart. As visitors wander through the gallery, they are invited not only to observe but also to introspect. In this way, Kromosho transcends the role of a mere art exhibition—it becomes a conversation, a homecoming, and ultimately, a call to bear witness. Written by Shahbaz Nahian

Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025 Opens in Dhaka, Showcasing National Industry to Global Markets

A four-day international exhibition has commenced in Dhaka to present Bangladesh’s ceramic industry to local, global buyers and investors. Organized by the Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BCMEA), Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025, one of Asia’s largest and most influential international ceramic trade exhibitions, is being held at the International Convention City Bashundhara (ICCB). This fourth edition of the expo is set to host 135 companies and 300 global brands from 25 countries, including host Bangladesh, while more than 500 international delegates and buyers are scheduled to participate, underscoring the increasing global focus on Bangladesh’s rapidly expanding ceramic sector. BCMEA confirmed that the exhibition will feature three technical seminars, a job fair, extensive B2B and B2C meetings, live product demonstrations, spot-order opportunities, raffle draws, attractive giveaways, and the launch of new ceramic technologies and products. The exhibition is open to visitors free of charge from 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM daily and is expected to attract buyers, suppliers, and stakeholders from across the sector. Speaking at the opening ceremony, Commerce Adviser Sheikh Bashir Uddin said the industry, once fully dependent on imports, has now secured a strong position in global markets. He stressed the need for advanced technology adoption and uninterrupted energy supply to maintain production efficiency. The adviser added that the Interim Government will provide all necessary policy and regulatory support to accelerate the industry’s expansion. Following the inauguration, the adviser and distinguished guests visited various pavilions and stalls, where they praised the innovations and product displays. The commerce adviser expressed confidence that the sector will become increasingly export-driven. The event was presided over by BCMEA President Moinul Islam. Other speakers included Export Promotion Bureau Vice-Chairman Mohammad Hasan Arif, Italian Ambassador to Bangladesh Antonio Alessandro, BCMEA Senior Vice-Presidents Md Mamunur Rashid and Abdul Hakim Sumon, and BCMEA General Secretary Irfan Uddin. BCMEA President Moinul Islam noted that the ceramic industry has experienced rapid growth over the past decade. More than 70 factories producing tableware, tiles, and sanitary ware are currently in operation, serving a domestic market valued at Tk 8,000 crore annually. Over the last ten years, both production and investment have increased by nearly 150 percent. He added that Bangladesh now exports ceramic products to more than 50 countries, earning nearly Tk 500 crore in annual export revenue. Total industry investment exceeds Tk 18,000 crore, with the sector providing direct and indirect employment to approximately 500,000 workers. He further highlighted that major ceramic-producing nations, including China and India, are increasingly exploring investment opportunities in Bangladesh due to its competitive cost advantages and expanding global footprint. Fair Committee Chairman and BCMEA Secretary-General Irfan Uddin said Bangladeshi ceramic products are gaining international recognition for their quality, durability, and modern design. Demand is rising, and new global markets are opening for local manufacturers. He added that the expo will spotlight next-generation ceramic technologies, including automation, advanced digital printing, robotic handling, and upgraded production lines. “Smart tiles and sensor-integrated ceramic products, which are already popular worldwide, are expected to enter the domestic market soon. This expo will help local manufacturers connect with these emerging technologies,” he said. The event is supported by key industry partners. Sheltech Ceramics is serving as the Principal Sponsor, while DBL Ceramics, Akij Ceramics, and Meghna Ceramics are Platinum Sponsors. Gold Sponsors include Mir Ceramics, Abul Khayer Ceramics, HLT DLT, and SACMI, reflecting broad industry backing for the international expo. Written by: Mizanur Rahman Jewel

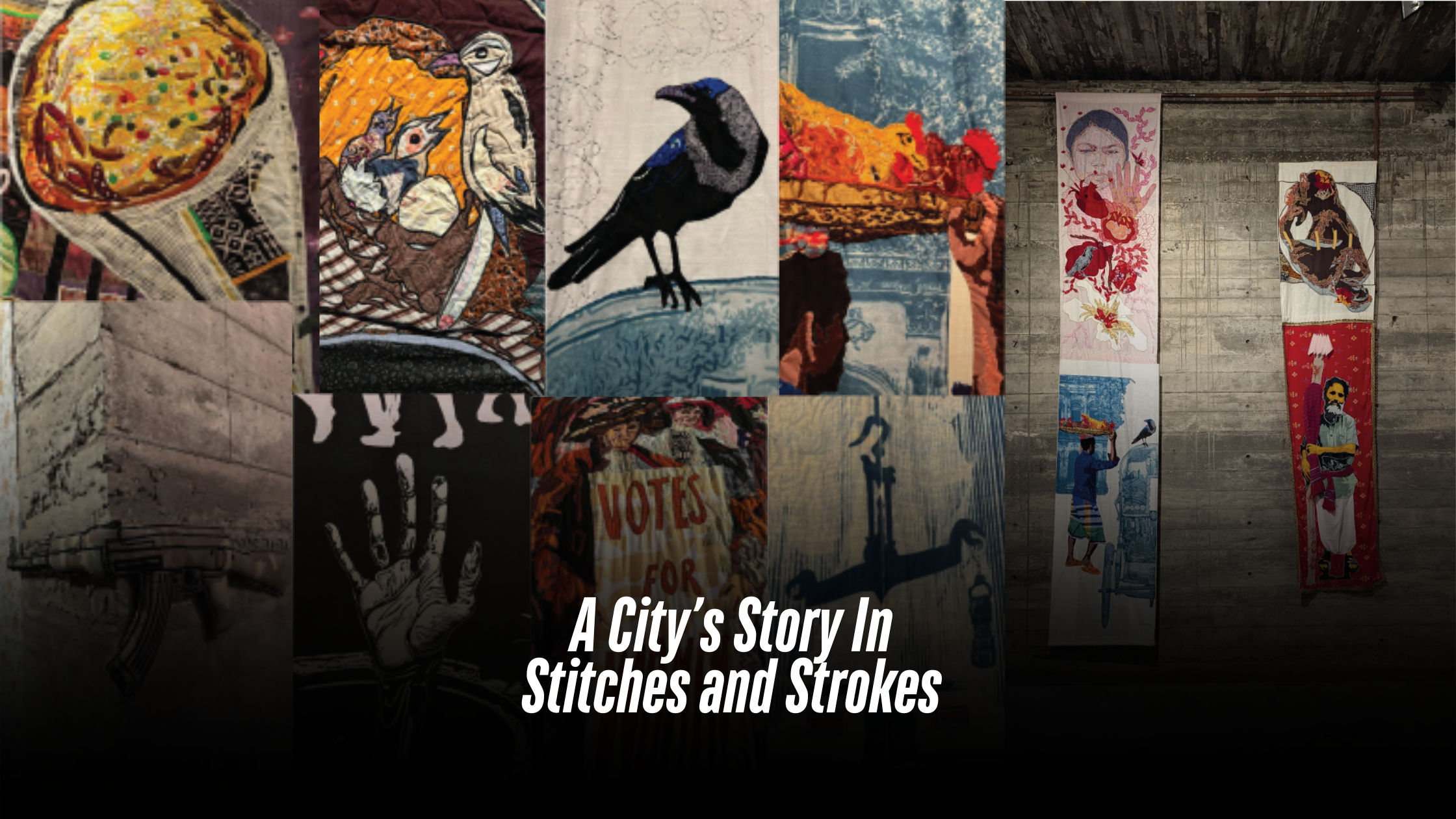

A City’s Story In Stitches and Strokes

Dhaka’s rapid urbanization is impossible to ignore. This city of relentless energy and transformation is a place where tradition and modernity collide amidst its bustling streets and ever-changing skyline. As the economic heart of Bangladesh, it draws thousands seeking better opportunities. But this comes at a cost: overcrowding, strained resources, and a growing disconnect between the old and the new. Against this backdrop, ShohorNama Dhaka Episode II sought to explore the city’s complexities through art. Launched in early 2024, the project brought together visual artists, architects, artisans, and students from the University of Dhaka’s Faculty of Fine Art to create a tapestry of urban narratives. And the exhibition of this project took place from February 15 to 25 at the level 4 under construction space of the capital’s Bengal Shilpalay. The exhibition was inaugurated by H.E. Marie Masdupuy, Ambassador of France to Bangladesh, on February 15, 2025. Titled after the project name, the multidisciplinary exhibition wove together the threads of urban life, resilience, and creativity. Presented by the Bengal Arts Programme in collaboration with the Britto Arts Trust, ShohorNama II was a visual love letter to Dhaka, its people, and their stories. From large appliqué tents to wood-cut prints, installations, and performance art, it was a celebration of Dhaka’s artistic topography. At its core, ShohorNama was about storytelling. One of the standout features is the Pakghor Project, a community kitchen born out of necessity during the devastating floods of 2024 in the Khulna region. Pakghor provided warm meals to 500 villagers for a week. But it became more than just a kitchen—it became a space for shared stories, resilience, and hope. The Dorjikhana Project takes a different approach, focusing on textiles and their cultural significance. Through appliqué and embroidery, artists explore the connection between traditional practices and the modern garment industry. The project also draws inspiration from Bangladesh’s fading circus traditions. Resulting in a stunning collection of textile art that speaks to both the past and the present. Another striking element of ShohorNama is its use of tents. Historically, tents have symbolized temporary shelter for nomadic communities, and in this exhibition, they represent the fluidity of migration—whether due to natural disasters, economic hardship, or political unrest. The Big Tent installation captured this impermanence, reflecting the challenges faced by marginalized communities. The exhibition also highlighted the collaborative spirit of the project. Workshops with the University of Dhaka’s Department of Printmaking and Department of Craft allowed students to contribute to large-scale works, such as woodcut prints and appliqué pieces. These workshops not only honed technical skills but also fostered a sense of shared purpose, blending individual creativity into a cohesive vision. The exhibition was a feast for the senses! As Dhaka continues to evolve, exhibitions like “ShohorNama Dhaka Episode II” remind us of the importance of preserving our stories and traditions. Through art, we can find common ground, build resilience, and imagine a better future. Written by: Shahbaz Nahian Photo: Bengal Art Foundation | Courtesy