Day: August 1, 2025

Designing with Light Living with Heart Architecture of Ziaul Sharif

In the narrow lanes of early 1990s Dhaka, a young boy paused in front of construction sites and miniature models displayed on black-and-white television sets. These fragments of the city—raw, unfinished, full of potential—captured his imagination. For Ziaul Sharif, architecture began not in a classroom, but in the rhythm of passing buildings, the dance of light on brick, and a deep curiosity about how spaces are made. Now the founder and principal architect of Vuu-Maatra Consultants, Ziaul Sharif is shaping a quietly radical vision for contemporary architecture in Bangladesh—one where light, air, greenery, and local wisdom are not design options, but essentials. A Creative Foundation Born in Rajshahi and raised in Dhaka, Ziaul Sharif grew up in a home where intellect and creativity were part of daily life. His father, MM Shahidullah, practised law with conviction; his mother, the late Mrs. Shireen Shahid, fostered a home filled with music, art, and community spirit. From teaching music to children at Ghashful Khelaghar Asor to painting and acting, Sharif’s early exposure to the arts enriched the spatial sensibility that now defines his work. After completing his education at Rayer Bazar High School and Dhaka City College, Sharif pursued architecture at BUET, one of Bangladesh’s most respected institutions. There, he studied under the renowned Professor Shamsul Wares and found himself drawn to the work of Louis Kahn—especially the National Parliament Building, whose poetic use of space and light remains a lasting influence. Design as Responsibility Sharif’s early professional journey included stints with Bashirul Haque & Associates, Indigenous Architects, and Nandan Architects. In 2006, he took on the resident architect role for Westin Dhaka, a five-star hotel project that refined his understanding of scale and detail. But it was in 2008, with the founding of Vuu-Maatra Consultants, that his practice truly found its voice. Today, the studio is home to 15 designers, architects, and engineers, and their portfolio spans from high-rise commercial buildings to hotel interiors and private residences. But what sets the firm apart isn’t the scale of its projects—it’s the intention behind them. “We don’t just design buildings,” says Sharif. “We design environments for life. For growing up, resting, healing, thinking. For breathing.” This approach is deeply humanistic, rooted in the belief that architecture has a profound impact on the mental and physical well-being of its occupants. In a city where poorly ventilated, densely packed housing is the norm, Architect Ziaul Sharif advocates for an alternative: buildings that breathe. Vasat Vita: A Living Prototype Nowhere is this philosophy more evident than in Vasat Vita, Architect Ziaul Sharif’s residence and studio in Dhaka’s Aftabnagar. Completed in 2022, this three-storey structure sits on a compact 200-square-metre plot but opens inward to an expansive experience of air, light, and greenery. Built with passive cooling principles inspired by Vaastu Shastra, the building features a central courtyard open to the sky, a waterbody that moderates internal temperatures, and a layered brick façade that filters sunlight while ensuring privacy. A ribbon of plants tucked between the perforated brick shell and the glass wall brings nature directly into the building’s envelope. “Vasat Vita is not just a home or an office,” Sharif explains. “It’s a lab for ideas. A demonstration of how we can live better, even in the tightest corners of Dhaka.” The project was recently featured in ArchDaily, highlighting its relevance not just to local contexts but to global conversations about compact urban sustainability, thermal comfort, and culturally responsive design. Architecture for People Architect Ziaul Sharif’s commitment to accessible design extends beyond his client list. Through Vuu-Maatra, he has initiated a pro-bono programme to offer free architectural services to families who cannot afford professional help. Projects in Khulna and Kushtia, including a residence for Aarti Rani Mandal, are built on this ethos of design as dignity—ensuring that even modest homes receive the same care and thought as luxury hotels. This vision challenges the long-held assumption that architecture is a service for the elite. “Everyone deserves a well-designed home,” Sharif insists. “Good architecture shouldn’t be a privilege. It’s a necessity.” A Future Rooted in the Past Sharif’s work draws as much from memory as it does from modern techniques. He recalls walking past old brick buildings in Old Dhaka, noticing how they aged gracefully, filtering air and light through intricate jaali patterns. These early experiences now manifest in his façades, his ventilation strategies, and his material choices. In an era obsessed with glass towers and instant spectacle, Ziaul Sharif’s architecture is refreshingly quiet. It invites you to pause. To feel. To notice how the air moves, how shadows stretch, and how a space can hold you gently. With every project, Sharif is not just building structures—he’s building the belief: that architecture can be beautiful, democratic, sustainable, and deeply personal. Vuu-Maatra Consultants is currently expanding its portfolio across Bangladesh, continuing its mission of designing with empathy, responsibility, and rooted imagination. Written by Fatima Nujhat Quaderi

Read More

Reviving the Roots: Conservation & Restoration Progress Reflections by Conservation Architect Abu Sayeed M Ahmed

At the anniversary celebration of Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine, esteemed conservation architect and heritage specialist Abu Sayeed M Ahmed presented “Reviving the Roots: Conservation and Restoration Progress”—a heartfelt journey through two decades of architectural conservation across Bangladesh. With vivid images and powerful anecdotes, he reminded the audience that conservation is not about romanticising ruins—it is about safeguarding identity, craftsmanship, and cultural continuity in a nation at risk of forgetting itself. “Every day in Dhaka, a piece of our heritage vanishes. Buildings are bulldozed in the name of development. But without roots, how can we grow a future that is truly ours?” Bringing History Back to Life Nimtali Deuri & Naib-Nazim Museum, Dhaka Abu Sayeed M Ahmed’s first major restoration was the late Mughal-era Nimtali Deuri in Old Dhaka. Hidden under layers of plaster. The restored gateway now houses the Naib-Nazim Museum, commemorating the deputy governors of Dhaka and reflecting a revived connection between the city and its Mughal past. Uttar Halishahar Mosque, Chattogram This 200-year-old mosque was facing demolition for modern expansion. Upon assessment, its authentic Mughal character became evident. Abu Sayeed’s team removed inappropriate cement layers, dismantled an added veranda, and re-clad it in traditional lime and surki. Locals now call it a “Gayebi Mosque”—as if it reappeared by miracle. Nearby, a new mosque by Architect Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury respectfully contrasts the old, echoing its jali motifs in modern concrete. Hanafi Jame Mosque, Keraniganj Once a modest family-owned mosque, it gained global recognition after restoration—winning a UNESCO Award. A new mosque built adjacent to it by Architect Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury, with full visibility of the old structure—offers a striking example of architectural dialogue between past and present, tradition and transparency. Rediscovering Rural Heritage Buraiich Maulvi Bari, Faridpur Neglected and engulfed by vines, this ancestral home seemed destined for ruin. Through sensitive restoration, it has been transformed into a heritage Airbnb, preserving its traditional character while offering economic sustainability. Period furniture, handpicked materials, and contextual storytelling give visitors a window into Bengal’s rural past. Mithamoin Kachari Bari, Kishoreganj This decaying administrative house—once thought beyond repair—was restored to reflect its original civic purpose. From a wild, overgrown ruin, it emerged as a dignified reminder of regional governance and colonial-era architecture, now serving as an active public building. Urban Civic Revival Narayanganj Municipal Building Among Bangladesh’s earliest municipal structures, it was at risk of being replaced. A dual solution—preserve the old and integrate it into the new. Today, it functions as the entrance to the new Nagar Bhaban (City Hall), and plans are underway to convert its upper level into a civic museum. Baro Sardar Bari, Sonargaon A Mughal-Colonial mansion from the Baro-Bhuiyan era, this structure was revived through corporate social responsibility. South Korea-based Youngone Corporation led the project under the leadership of CEO Kihak Sung, who has familial roots in the region. This model highlights how private sector investment can play a crucial role in cultural restoration. Reviving Lost Icons Dhaka Gate (Mir Jumla Gate) Once a neglected and overgrown monument, the historic city gate has been revitalised with its original grandeur—complete with a replicated fire cannon that signals its defensive legacy. Rose Garden Palace, Tikatuli, Dhaka A jewel of Dhaka’s architectural heritage, the Rose Garden was meticulously restored—from stained-glass panels to ornamental plasterwork. Where pieces were missing, they were reconstructed based on archival records, ensuring authenticity over imitation. Hammam Khana, Lalbagh Fort Perhaps the most complex restoration, the Mughal-era bathhouse had suffered colonial and post-colonial misuse. Funded by the U.S. Ambassador’s Fund, the project uncovered a breathtaking pavilion structure, restored lighting from above (true to hammam tradition), and reestablished the original spatial and sensory quality of the Mughal bathhouse. Crafting the Future with the Past Reviving Chini Tikri Ornamentation A rare local tradition, Chini Tikri—the use of broken ceramic dinnerware to form decorative motifs—was resurrected. The team digitally reconstructed patterns, reproduced the plates, broke them and reapplied them by hand. This craft was even adapted into a contemporary mosque in Noakhali, designed by Architect Mamnoon Murshed Chowdhury and Architect Mahmudul Anwar Riyaad, using waste ceramic products donated by Monno Ceramics. These projects demonstrate what is possible when craftsmanship, community, and conservation come together. They are not just restorations—they are cultural revivals, offering spaces where memory, faith, and identity continue to live. Written by Samia Sharmin Biva

Read More

Clay Dreams Crafted by Hand Ali Ceramic Industry Limited

A Parcel That Changed Everything In the early 1980s, a seemingly ordinary parcel delivered from Italy to a Bangladeshi family quietly set the stage for a life-changing transformation. Inside were handmade clay tiles—simple, earthy, and elegant—that inspired a new industrial journey rooted in tradition. The arrival of the tiles sparked an unexpected curiosity, drawing the family, engaged in ship management, into the intricate world of terracotta craftsmanship. This newfound passion led them from coastal shipping operations to the rural “Pal Para” villages, where generations of potters lived and worked. Decades later, that spark has evolved into Ali Ceramic Industry Ltd (ACIL), a rising name in Bangladesh’s ceramic sector. The company is now dedicated to producing 100% eco-friendly terracotta tiles, continuing a legacy built over 43 years. Backed by deep experience and a commitment to preserving clay artistry, ACIL is on a mission to blend sustainability with tradition. However, the ceramic maker had to go through numerous hurdles to reach today’s position. From economic turmoil to energy challenges, Ali Ceramic’s journey has tested its resilience—making its commitment to green craftsmanship truly admirable. From Shipping to Shaping Clay Before entering the ceramic business in 1982, the family of Ali Askar—now the Managing Director of ACIL—was involved in managing ships. Askar himself was just a Grade 9 student when he first began assisting in the family’s factory office. What started as part-time help during his school years gradually grew into a lifelong calling. The pivotal moment came through a surprising phone call. One day, Askar’s father was contacted by an Italian friend who asked if a product could be manufactured in Bangladesh. Without disclosing details, the friend sent a parcel. Inside were handmade clay tiles—a product so visually striking that it would eventually redefine the family’s business path. In Search of the Perfect Artisan Motivated by the parcel, Askar set out on a mission to find skilled artisans capable of replicating such craftsmanship. He travelled across Bangladesh, visiting various districts and exploring ‘Pal Para’—traditional villages of potters where pottery is not just a livelihood, but a way of life. After surveying several regions, Askar discovered exceptional potters in Satkhira. The Italian friend even joined a visit to the village and was impressed by the quality of work. This validation paved the way for launching an export-oriented business producing 100% eco-friendly handmade terracotta tiles under the name Maa Cottos Inc. Maa Cottos and Nikita International: A Legacy in Clay Maa Cottos Inc. serves as the parent company of ACIL, while Nikita International—another venture under the same umbrella—also manufactures 100% handmade terracotta tiles. Founded in 1982 as a family-run enterprise, Nikita International has grown into the largest handmade tile manufacturer not only in Bangladesh but across Southeast Asia. Over the past four decades, the company has built a reputation for high-quality structural clay products, including roof tiles, wall cladding tiles, and floor tiles. Their dedicated in-house research and development team continues to innovate, ensuring they remain relevant in both domestic and international markets. While Nikita International specialises in a broad range of traditional clay products, ACIL has taken a more modern approach, focusing on high-end machine-made terracotta tiles designed for contemporary architectural projects. Ali Ceramic’s Battle to Rise “Ali Ceramic was established in 2021, but its commercial production began in July 2024,” said Ali Askar. With a current daily output of 40,000 square feet of tiles and 170 employees, the company has already made a strong start. Its total investment stands at Tk 1.5 billion. However, Askar noted that despite this solid foundation, ACIL’s growth is being hampered by external challenges such as political instability and economic uncertainty. The July Uprising One such challenge emerged shortly after ACIL began full-scale production. Within a year, Bangladesh was shaken by the July Uprising, which brought government development projects to a halt. According to Askar, many of the contractors they had established relationships with were replaced in the wake of political upheaval, severing existing business ties. The re-tendering process for paused projects introduced further delays and added a new layer of unpredictability to ACIL’s business landscape. Production Challenges: Energy and Raw Materials In addition to political disruption, ACIL has faced ongoing operational difficulties. A key concern is the absence of a Titas gas connection, which has forced the company to rely on liquefied petroleum gas (LPG)—a costlier alternative that significantly raises production expenses. Despite these setbacks, ACIL has managed to maintain product quality. Clay is sourced from regions such as Gazipur and Sylhet, chosen for their reliable natural composition and consistency, ensuring each tile meets the company’s exacting standards. Handmade Tiles: Craft Holds the Crown While machine-made terracotta tiles remain common among Bangladeshi producers such as Mirpur Ceramic Works Ltd. and Khadim Ceramics Ltd., there is a noticeable shift in the global market. Foreign buyers are increasingly drawn to handmade tiles for their aesthetic charm and artisanal value. This growing demand reaffirmed Askar’s decision to launch ACIL as a complement to the handmade offerings already being exported by Maa Cottos Inc. and Nikita International. Reaching 22 Global Destinations Today, Askar proudly notes that handmade tiles produced under the group’s brands are exported to 22 countries—including Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and Japan. The appeal lies in the product’s eco-friendly, handcrafted nature, which resonates strongly with environmentally conscious consumers around the world. Why Imported Tiles Still Dominate the Market Despite this progress, the local ceramic industry continues to face stiff competition from imports. Around 20–25% of Bangladesh’s ceramic demand is still met by foreign tiles, mainly from China, Spain, Turkey, and Vietnam. This dependence stems from Bangladesh lagging nearly five years behind in design and innovation. Although the country has no shortage of skilled ceramic professionals, much of this talent remains underutilized due to a lack of investment in advanced machinery and modern design capabilities. Until the industry catches up in both creativity and technology, imported tiles will likely continue to dominate the high-end segment of the market. A

Read More

Export Woes Overlooked in FY26 Budget Ceramic sector left in the cold

The interim government’s Tk 7.9 trillion budgets for FY2025-26 have drawn criticism for lacking bold measures to strengthen export-oriented sectors, including garments, leather, pharmaceuticals, and ceramics—key drivers of Bangladesh’s economy. Despite persistent demands from businesses, the budget offers no concrete plans to modernize ports, ensure stable gas and electricity supply, or reduce logistical hurdles that cripple competitiveness. The leather sector, struggling with compliance and environmental challenges, finds no support for factory upgrades, while pharmaceuticals—a growing export segment—receive no incentives for R&D or market expansion. Similarly, the ceramic industry, which relies on imported raw materials, sees no relief from high production costs. With private investment stagnant and unemployment high, industry leaders argue that the budget missed a crucial opportunity to implement structural reforms, widen the tax net, and boost global competitiveness—essential steps for sustaining export growth and economic stability. Youth Job Crisis, Poverty Fight Missing in Action The interim government’s first budget has failed to address the core grievances that sparked July 2024’s mass uprising — unemployment and inequality. Despite 20% graduate unemployment and 30% youth disengagement from work or education, the budget offers only token funds for self-employment schemes without structural solutions. Social safety nets saw marginal increases, while allocations for education and health have remained stagnant. With 40 million below the poverty line—and a World Bank warning of worsening poverty—the budget lacks comprehensive anti-poverty strategies. Economists describe it as a “stopgap budget” that maintains the status quo rather than addressing the employment crisis that fueled last year’s protests. The absence of bold job creation measures suggests continued economic discontent among the youth. Budget Targets Overly Ambitious: Economists Economists have raised concerns over Bangladesh’s proposed FY2025-26 budget, calling its revenue, growth, and inflation targets unrealistic given current economic challenges. While noting some positive measures like reduced VAT on LNG and lower advance taxes, they highlighted structural weaknesses in tax administration and insufficient focus on job creation as key risks. Revenue & Inflation Doubts The revenue collection goal was seen as unattainable without tackling tax evasion, while inflation projections were deemed too optimistic amid persistent price pressures. Reforms Missing Experts pointed to a lack of meaningful reforms in customs, logistics, and labor markets, with particular concern over stagnant education and healthcare spending despite their importance for long-term growth. Implementation Challenges While some trade facilitation efforts like the National Single Window were acknowledged, economists warned that bureaucratic inefficiencies and resistance to change continue to hinder progress on critical economic reforms. Little to No Relief for Ceramic Sector The ceramic sector received no significant fiscal relief in the recently passed national budget for FY2025–26, despite its growing contribution to import substitution, employment generation, and sustainable construction, according to stakeholders. The Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers & Exporters Association (BCMEA) has expressed disappointment over the government’s failure to address longstanding demands, which could have reduced production costs and made locally produced tiles and sanitary ware more competitive against imports. The BCMEA had proposed that customs authorities allow up to 35% deduction during import-stage valuation for moisture, unusable chemical substances, and volatile components in imported raw materials such as China Clay (HS Code 2507.00.10) and Ball Clay (HS Code 2508.40.10). These clays, entirely import-dependent, naturally contain 30–35% wastage components, and further losses occur during processing—sometimes up to 40%. However, import duties are still calculated on 100% of the gross weight, significantly increasing costs for producers. The association also demanded the withdrawal of the 15% supplementary duty (SD) on locally produced tiles (HS Code 69.07) and the 10% SD on sanitary ware (HS Code 69.10). According to the BCMEA, these products are no longer considered luxury items but are integral building materials, widely used in both residential and commercial construction. They also play a vital role in promoting public health and environmental sustainability. “The government talks about affordable housing and sanitation for all, yet continues to impose unnecessary duties on locally made essential products,” said Moynul Islam, President, BCMEA, adding that, “If these unjustified duties are not withdrawn, local manufacturers will lose competitiveness, while consumers will continue to suffer from high prices amid inflation.” He also pointed out that the absence of incentives for value-added manufacturing contradicts the government’s broader goals of economic diversification and green growth. The sector, which heavily relies on imported raw materials, has already been hit hard by the appreciating US dollar and rising freight costs. The BCMEA reiterated that removing these fiscal burdens would not only lower production costs and market prices but also encourage further investment and expansion in domestic manufacturing, reducing dependence on imports and generating more employment. Economist Questions Budget’s Effectiveness Dr. M Masrur Reaz, Chairman of Policy Exchange Bangladesh, expressed disappointment that the proposed budget lacks clear roadmaps for structural reforms, employment generation, and investment stimulation. He pointed out the absence of bold measures to address the country’s core economic challenges. The economist described the budget’s revenue and growth targets as overly optimistic given the current political uncertainty and post-election economic climate. “Inflation may have eased slightly, but the government’s projections remain unrealistic without substantial investment and job creation,” Reaz stated. While not opposing the principle, Reaz questioned the timing of proposed salary increases for government employees, suggesting the measure may be premature given fiscal constraints. Reaz offered targeted recommendations for key sectors: Agri-business / Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG): Formalize informal trade channels and improve tax compliance. Telecommunications: Reduce tax burdens to accelerate digital inclusion. Tobacco: Maintain current tax structures to combat illicit trade while ensuring revenue stability. The economist acknowledged some positive steps including: Reduced VAT on LNG imports. Lower advance taxes on raw materials. Decreased land registration fees. However, he criticized: Increased VAT on yarn. Higher turnover taxes for loss-making businesses. Lack of initiatives for rural women’s employment. Dr. Reaz concluded that while containing some business-friendly elements, the budget ultimately fails to deliver transformative changes needed to address Bangladesh’s employment crisis and economic stagnation. The absence of comprehensive poverty reduction

Read More

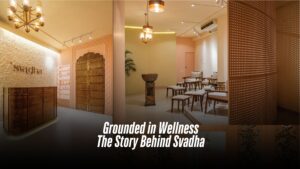

Grounded in Wellness: The Story Behind Svadha

Over the past decade, Bangladesh’s spa and salon culture has gone through a quiet but striking revolution. The once-flashy, first-service catered parlours have given way to curated wellness havens that prioritize experience over gimmicks. From Faux-Thai facades, a new design language is emerging. At the forefront of this transformation is Svadha, the country’s first salon to fully integrate Ayurveda into its core philosophy. But it’s not just their services that set them apart, it’s the atmosphere. Their aesthetic blends the royalty of Mughal architecture with the earthy soul of Marrakesh, creating a space that feels both grounded and luxurious. Svadha is a family-led vision brought to life by Rumjhum Fattah, her brother, Md Golam Rezwan, and sister-in-law, Behtarin Chowdhury Ridma. While the trio has long been a part of Bangladesh’s RMG sector, Svadha marks their first foray into the world of beauty and wellness, and they’re doing it on their terms. The name Svadha, derived from Sanskrit, beautifully translates to “self-care” and “self-love”—an ethos that defines everything the brand stands for. “At Svadha, we’re not here to sell beauty or grooming services,” says Rumjhum. “We’re here to create a space where people can slow down, tune in, and prioritize their well-being.” Svadha is located in the heart of Gulshan Avenue and comprises a total area of around 3300 square feet. The interior, designed by the creative minds at Studio R.A.R., is a visual and sensory ode to stillness, grounding, and mindful indulgence. “Svadha is a true embodiment of peace and tranquillity,” shares co-founder Behtarin Chowdhury Ridma. “From the lounge to the treatment rooms, we wanted every inch to feel like a retreat, where the stress of daily life simply melts away. To achieve that, we explored a palette of earthy tones and tactile, natural materials.” She pointed out that most salons in the city are built around speed and efficiency, often at the expense of comfort. “Everything is so fast-paced—walk in, get the service, walk out. There’s hardly ever a moment to truly unwind,” she reflected. At Svadha, the philosophy is deliberately different. The space is intentionally kept open and airy, avoiding unnecessary partitions or a heavy-handed layout. “We wanted to let the space breathe, just like our clients,” she added. There are no false ceilings or forced divisions; instead, the design embraces fluidity, allowing natural light and movement to flow freely. Catering to working women, Svadha brands itself as a wellness retreat. “Our clients come not just to look good, but to feel good. After long hours at work, they deserve to be unrushed, cared for, and truly pampered.” Drawing inspiration from Moroccan and Indian architectural traditions, the space features intricately carved wooden mirror frames, classic oil lamps, and a striking antique doorway that sets the tone from the moment you enter. A gentle water fountain hums in the background, further enhancing the atmosphere of calm. “We wanted to infuse the space with elements of nature and its calming rhythms,” shared Rumjhum. “The water fountain, placed thoughtfully within the layout, is a quiet homage to that intention, a gentle nod to movement and serenity. Throughout the space, you will find indoor plants too” Lighting, too, was carefully curated to complement this ambiance. There’s a deliberate avoidance of harsh, bright lights. Most areas are bathed in soft, ambient illumination, dimmed and mellow to encourage relaxation. However, in zones like the makeup and hair stations, where precision is key, the lighting is thoughtfully intensified to ensure clarity without disrupting the overall calm. One of the standout features of the salon is the textured wall next to the reception where the metal brand name is hung. There is also a graffiti wall, commissioned by a Fine Art student of Dhaka University where Mughal-themed flowers are painted. Every piece of furniture in the salon has been custom-crafted in-house. Each zone has been thoughtfully planned to serve its specific purpose, whether it’s a quiet waiting lounge, a private treatment room, or a styling station. Every detail, down to the custom-built furniture, typography on the walls, and curated lighting reflects Svadha’s vision of a wellness destination that feels both intimate and elegant. Written by Kaniz F Supriya

Read More

Timber Tales sparks a dialogue in wood and ink

The ongoing exhibition titled Timber Tales at La Galerie, Alliance Française de Dhaka invites audiences to experience the collaborative journey of three emerging artists who explore memory, process, and material through the art of woodcut printmaking. Within the exhibition, a faint, earthy scent of wood and ink hangs in the air. Walking into the gallery, some might find themselves pausing longer than expected, tracing the grain of the wood as if searching for their own stories between the lines. The exhibition features three artists—Rakib Alam Shanto, Shakil Mridha, and Abu Al Naeem—who express individuality through their woodcut prints. This contemplative exhibition is running from June 17 to June 25, 2025. Curated by the artists themselves, the exhibition reimagines the possibilities of woodcuts as a medium. Here, the tactile intimacy of carved timber meets the visual language of reflection, nostalgia, and search. As you wander through the space, individual voices emerge. Shakil Mridha’s work, with its minimalistic yet profound geometric forms, feels like a contemporary ode to Bangladeshi folk art, skillfully abstracting familiar motifs. Rakib Alam Shanto’s large-scale black-and-white pieces command attention, a powerful revival of a tradition, showcasing his remarkable focus. Abu Al Naeem’s pieces, often abstract, subtly reveal hidden figures, reflecting his continuous exploration of materials and techniques. Each artist, in their unique way, elevates woodcut beyond mere reproduction, transforming it into a medium of profound personal expression. And through that expression, each of their work reflects the heart of the creative process, where stories are carved into existence. At the heart of Timber Tales is a tribute to beginnings, to the mentor who shaped them, and to the space where it all began. Their acknowledgement of Professor Md. Anisuzzaman, whose generous guidance helped steer their vision, reveals the deeply collaborative ethos of the show. “This is where it all began—for the three of us,” reads a line from the exhibition note, underscoring the intimate bond between craft, community, and coming-of-age. In an era of digital immediacy, there’s something revolutionary about the deliberate slowness of woodcuts. And the three artists have breathed new life into the ancient art of woodcut. More than just a technique, it’s a dialogue between human touch and natural materials. Each frame holds a deeper narrative of tireless dedication—the careful selection of wood, the precise cuts, the methodical inking, and the final, expectant press. Open to all and continuing until 25 June 2025, Timber Tales will leave visitors with more than just images on paper. In a city rushing to reinvent itself, the exhibition feels like a pause, a reminder of our roots with a sense of belonging—to the artists, to the materials, and to the timeless, meditative act of making. Written by Samira Ahsan

Read More

KARMASANGSTHAN BANK: Vision for Inclusive Growth

Karmasangsthan Bank is a unique state-owned social bank in Bangladesh, established in 1998 to turn unemployed youth into entrepreneurs. Its mission is to extend financial services to underserved communities and foster sustainable businesses. Literally translated as the “Employment Bank,” it empowers aspiring entrepreneurs to transform their ideas into sustainable ventures. Born from a national vision for inclusive economic development, the bank has dedicated itself to bridging the financial gap for underserved segments of society, particularly in rural areas. This focus on inclusive growth sets it apart from conventional commercial banks and makes it an essential instrument for national development. Under a government mandate and with initial capital of Tk 300 crore, Karmasangsthan Bank was created to tackle unemployment by funding small enterprises. Over time, government backing has expanded its loan pool to around Tk 4,500 crore, amplifying its reach. Its core purpose remains nurturing grassroots entrepreneurship and uplifting marginalised groups. Karmasangsthan Bank tailors its products to the needs of unemployed youth and small-scale entrepreneurs. Its flagship offerings include: Low-interest and interest-free loans for start-up ventures, microcredit schemes designed for first-time borrowers and special financing packages for persons with disabilities. The bank’s board unites professionals from financial and administrative backgrounds, ensuring strategic oversight and mission alignment. In November 2024, Dr AFM Matiur Rahman took the helm as the 14th chairman, while Arun Kumar Chowdhury guides daily operations as Managing Director. Their stewardship has driven both stability and innovation. With over 285 branches and 1,800 employees spanning every district and most upazilas, Karmasangsthan Bank brings its services to urban centres and remote villages alike. This footprint underscores its commitment to rural financial inclusion and fuels broader socio-economic development across Bangladesh. Beyond financing, Karmasangsthan Bank serves as a catalyst for community uplift. Its operations blend government policy, entrepreneurial mentoring, and localised development initiatives—proving that a bank can be a powerful tool for social transformation. To reach the unbanked, the bank is rolling out mobile banking apps, digital payment gateways, and online portals. These technologies bridge geographic divides, making services more accessible to rural and marginalised populations. Through initiatives like this, Karmasangsthan Bank continues to fulfil its mission of fostering a balanced economic structure by converting the population into productive manpower and reducing unemployment. Currently, Bangladeshi citizens aged 18 to 50 are eligible for loans up to Tk 5 lakh without collateral and up to Tk 75 lakh with collateral. Thanks to its outstanding performance across key indicators, Karmasangsthan Bank ranked first among state-owned specialised banks for the last two consecutive fiscal years. The government approved the construction of a 25-storey multi-purpose building atop a four-storey basement at a cost of Tk 260 crore. This project will be built on 37 decimals of land formerly belonging to the Times-Bangla Trust in Motijheel, Dhaka, now registered under the bank’s name. Since Karmasangsthan Bank operates under a similar model as Grameen Bank, the government should consider granting it full tax exemption. This measure would enable the bank to lower its interest rates further, providing greater support to unemployed and poor borrowers. Additionally, the nation would benefit from more affordable products, fostering a competitive market environment. Bank’s Performance Karmasangsthan Bank has lent Tk 18,000 crore to over 1.2 million youth, indirectly benefiting some 4.2 million people. Its recovery rate is about 96%. Currently, approximately 2,25,000 entrepreneurs—30% of whom are new each year and 40% of whom are women—tap into its schemes, with a total of about Tk 4,300 crore in outstanding loans. In the last fiscal year (July 2024–June 2025), Tk 2,838 crore was disbursed in self-employment loans to 1,25,000 entrepreneurs. Tracking job creation and enterprise growth provides clear evidence of its social footprint. The breakdown includes: Cattle fattening: Tk 1,595 crore (56.2%) to 76,744 individuals. Dairy farms: Tk 525.36 crore (18.5%) to 24,712 individuals. Fisheries: Tk 126.75 crore (4.5%) to 5,832 individuals. Poultry farms: Tk 15.43 crore (0.6%) to 745 individuals. Agro-based industries and nurseries: Tk 11.28 crore (0.4%) to 530 individuals. Commercial sector: Tk 160.35 crore (5.65%) to 7,309 individuals. Service sector: Tk 76 crore (2.65%) to 3,669 individuals. Small and cottage industries: Tk 53.84 crore (2%) to 2,531 individuals. Other sectors: Tk 275 crore (9.5%) to 2,100 individuals. During the same period, the bank earned Tk 408.37 crore in revenue against operational expenses of Tk 270.33 crore. Its pre-tax profit stood at Tk 138.04 crore, and it paid Tk 19 crore in advance corporate income tax. Customer Success Stories Rezaul Haque, a 45-year-old resident of Sundarpur in Paba Upazila (Rajshahi), transformed his life through commercial fish farming. With an initial loan of Tk 50,000 from the Rajshahi branch of Karmasangsthan Bank, Rezaul received subsequent training from the Department of Fisheries and the Department of Youth Development. Starting modestly, his venture expanded over 95 bighas of water bodies. Today, his investment has soared past Tk 1 crore, and he earns an annual income of about Tk 10 lakh. His journey not only provided him with financial stability but also inspired many local youths to explore similar opportunities, contributing to the region’s growing protein demand. Broadening Horizons in Aquaculture Another remarkable example is Borhan Uddin from Bagsara village. After securing a loan from the bank, Borhan invested Tk 75 lakh in a fish-farming business. With clear prospects for future expansion, his investment is expected to hit Tk 1 crore in the near future. His success story is a testament to how specialised loan products, combined with financial guidance, can spur rapid growth and foster entrepreneurship at the grassroots level. Retail and Small Business Beyond aquaculture, Karmasangsthan Bank has also empowered entrepreneurs in the retail and small-business sectors. For instance, Shahajahan Ali, owner of a local enterprise in Nawhata Municipality Market, has been utilising the bank’s credit support for over a decade to sustain and grow his business. Similarly, Mokbul Hossain, who runs a shoe store in the same market, successfully expanded his operations with consistent financial backing. Beef Fattening and Dairy To promote food security and create

Read More

CERAMIC EXPO BANGLADESH 2025 EXPLORE THE WORLD OF CERAMICS

Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025 is fast approaching, promising to be the largest and most prestigious exhibition in the country. The event will bring together a wide range of manufacturers, innovators, professionals, and enthusiasts from both the local and global ceramic industries. The Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BCMEA) will organize the event at the International Convention City Bashundhara (ICCB). This four-day event is more than just an expo – it’s a celebration of innovation, networking, and excellence in ceramics. Key Highlights of Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025 B2B & B2C Networking Opportunities Business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) sessions will allow exhibitors to showcase new products, technologies, and innovations to their target audiences. These sessions will help businesses explore opportunities for strategic collaboration and expansion. Awards & Recognitions An exciting feature of the event is honouring exhibitors with the Best Pavilion and Stall Design Awards. Exhibitors will design their pavilions and stalls based on their brand identity or how they wish to portray it to their target audience. Winners will be selected by a distinguished jury. A Lifetime Achievement Award has been introduced to honour an individual who has made a significant contribution to the development and growth of Bangladesh’s ceramic industry. Knowledge-Driven Seminars & Conferences The 2025 edition of the expo will host five insightful seminars and panel discussions. These sessions will feature prominent industry experts, architects, engineers, and thought leaders. Topics will focus on the future of ceramics, technological advancements, sustainability, and design innovations. Job Fair For job seekers, students, and professionals, Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025 offers a golden opportunity to connect with leading ceramic companies. Visitors will be able to submit their résumés to explore job opportunities with prominent ceramic manufacturers in Bangladesh. Visitor Engagement & Raffle Draw BCMEA will distribute exciting gifts and organise a raffle draw to appreciate and encourage maximum visitor participation. These activities aim to celebrate the continued support for the industry’s growth. Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025 proudly invites all to explore, exhibit, network, and learn through the event. It is a gateway to the future of ceramics and a grand opportunity for the ceramic industry to grow further. Written by Preety Dey

Read More

A Legacy of ABC Group Trust, Tenacity and Timeless Vision

In a business landscape where many joint ventures of the past century faltered under fractured trust and unchecked ambition, ABC Group shines as a beacon of integrity, resilience, and generational continuity. For over five decades, the organisation has not only transformed skylines but also redefined the very essence of partnership—proving that enduring success is built not solely on ambition, but on unwavering principles, a shared vision, and an unshakable commitment to people both within and beyond the company. “Partnerships rarely fail because of market forces,” reflects Subhash Chandra Ghosh, Chairman of ABC Group. “They collapse when trust erodes—when dishonesty, greed, or envy take root. Our survival has been anchored in three simple values: transparency in every transaction, fairness in every decision, and respect in every relationship.” This philosophy has guided ABC Group through the passing of its five founding partners, enabling a seamless transition of leadership to the next generation while preserving the spirit of its origins. Today, the group stands as a diversified conglomerate with four core divisions: ABC Limited (Construction), ABC Real Estate Limited (Property Development), ABC BPL (Ready-Mix Concrete Manufacturing & Supply), and the newly launched ABC FL (Facility Management Services). Each division plays a pivotal role in Bangladesh’s infrastructural and economic growth. Beyond construction and real estate, the group’s influence extends into the financial sector. The directors of ABC have been prominent founding shareholders of Mutual Trust Bank Limited (MTBL), one of Bangladesh’s most successful and trusted private banks. Rashed A. Chowdhury, the son of ABC’s founding chairman, Saifuddin Ahmed Chowdhury, now serves as Chairman of MTBL, further cementing the ABC Family’s legacy in nation-building across industries. The Genesis: Building Dreams from the Ground Up The story of ABC Group is intertwined with the birth of a nation. In 1972, in the stirring aftermath of Bangladesh’s independence, a bold vision took shape. Amirul Islam, his brother Nazrul Islam, and Saifuddin Ahmed Chowdhury—along with two associates—laid the cornerstone of Associated Builders Corporation (ABC) Limited. Soon thereafter, civil engineer Subhash Chandra Ghosh and architect Mostaqur Rahman joined the venture, forming a partnership that would one day redefine the country’s urban fabric. In those early days, ABC was not an empire—it was a dream defined by determination. With no heavy machinery, limited skilled labour, and scarce capital, the founders relied on resilience, strategic alliances, and sheer perseverance. Subhash Chandra Ghosh, then a young engineer, had begun his career at Yakub Limited earning a modest salary of 350 taka. When the company’s West Pakistani owner fled post-independence, Subhash and a colleague assumed leadership, keeping the operations afloat. It was during those turbulent times that fate brought him together with Amirul Islam—a meeting that would sow the seeds of an enduring legacy. Mr. Ghosh recalls with pride that his stake in the company was secured not through capital but through the strength of a handshake, a testament to an era when a man’s word was his bond. Forging a Future: The Rise of an Empire ABC’s first major breakthrough came with a two-crore-taka contract for the Bangladesh Machine Tools Factory, marking the beginning of its ascent. Landmark projects soon followed—Ashuganj Fertilizer Factory, Khulna Thermal Power Plant, and the Gorai Bridge—all setting new benchmarks in engineering excellence. Over the decades, ABC Group’s portfolio expanded to include national icons such as the Grameenphone Headquarters, North South University, BRAC University’s New Campus, and the Third Terminal of Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport. Currently, ABC Limited is building the prestigious Aga Khan Academy campus at Basundhara. By the late 1980s, ABC’s vision expanded beyond construction into real estate. In 1988, ABC Real Estate Limited (ABC REL) was born—a bold move at a time when the concept of apartment living was still in its infancy in Dhaka. From Concrete Foundations to Living Communities Challenges abounded: land scarcity, public skepticism toward apartment living, and the absence of clear registration laws. Yet, through meticulous planning, superior design, and uncompromising transparency, ABC Real Estate earned trust—one project at a time. The company has always approached the market with caution to avoid overambitious trading, a common pitfall in the real estate industry. Today, it has delivered more than 1,880 apartments across 70 projects in prime locations such as Uttara, Banani, Dhanmondi, Gulshan, Baridhara, and Chittagong. A crowning achievement is The Oasis at Ispahani Colony, an international-standard gated community in Moghbazar that spans 14.5 bighas. Completing 457 units within 70 months—despite various crises induced by the pandemic—is a true testament to ABC Real Estate’s planning and resilience. A New Vision: Affordable Excellence Beyond Dhaka Under the leadership of Srabanti Datta and Shougata Ghosh, ABC Real Estate is shifting its focus toward large-scale residential projects in mid-cost areas of Dhaka and its suburban localities. Their vision is clear: to provide quality housing with modern amenities accessible to the upper-middle class at reasonable prices. “Dhaka’s land prices have made premium housing unaffordable for many,” explains Srabanti Datta. “By developing well-planned communities in emerging zones, we can offer spacious living, green spaces, and modern facilities—without the exorbitant costs of the city center. With The Oasis, we are now confident that ABC has the best set of pragmatic ideas, skilled people, and strategic planning tools to successfully deliver massive projects beyond mere flashy brochures.” Upcoming projects like The Orchard exemplify this strategy, combining affordability with international standards. Additionally, the group is exploring expansion to Narayanganj, ensuring sustainable urban growth beyond the capital’s high value yet densely populated areas. Diversification & Innovation: The ABC Ecosystem Beyond construction and real estate, ABC Group has strategically diversified into ready-mix concrete (ABC BPL) and facility management (ABC FL), ensuring control over quality and service delivery across the board. ABC BPL is one of the country’s leading suppliers of ready-mix concrete, known for its precision, durability, and efficiency in high-rise constructions. ABC FL—the newly launched division—provides high-quality facility management services in Bangladesh, offering maintenance, security, and operational excellence for both residential and commercial properties. The Heart Behind the Helm: A Symphony

Read More

You Actually Want to Hang Out in! Brutown’s Got a Funky New Friend: Say Hello to Nervosa.

For those who enjoy café culture, a delightful spot has opened its doors to Dhaka’s vibrant crowd. Nervosa is a cafe located on Siddheswari Road, Dhaka, at the edge of a bustling neighbourhood—just above Brutown, which has long been a favorite in the heart of Bailey Road. Why Nervosa The name, “Nervosa,” is a deliberate nod to the beloved sitcom Frasier, where a fictional coffee shop of the same name served as a backdrop for the characters’ daily lives. Sabeel Rahman, CEO and Proprietor of BruTown and Nervosa, explains his choice with a playful intrigue: “The question of ‘Why Nervosa?’ is what makes it captivating. It draws attention, it’s a memorable name.” Consider Nervosa as the upscale, fancy, artistic neighbor of the popular cafe, BruTown, finding its niche in the community. Behind the Scenes Rehnuma Tasnim Sheefa, the principal architect of Parti.studio elaborates on the design philosophy: “Every design develops from a concept or a vision and if for a restaurant or a cafe, the branding has its influence as well. For Nervosa, that concept was built on strong character and a vibrant color palette, designed to draw a younger crowd into the cafe, as envisioned by the owner. When working in a public realm like cafes, as an architect I also had to focus on the psychological impact a person would have with the colors and the characters.” The color palette evolved gradually. Pale Orange took precedence, aligning with the theme initially, with striking illustrations bringing life to the walls. To make the illustrations stand out, a monochrome backdrop was introduced for the floors, ceilings, and other walls, allowing the boldly patterned and colored furniture to shine truly. The exposed brick on some of the walls adds a touch of urban grit, while the wooden flooring brings warmth and texture; keeping them aligned with the basic pale orange color. The cafe culture in Dhaka thrives on connection. Comfortable seating arrangements encourage heartfelt conversations, from an upcycled plush couch perfect for intimate gatherings to communal tables fostering spontaneous interactions. Nervosa goes a step further with cozy bookshelves stocked with comics and novels, perfect for anyone who wants to settle in with a good read. Instagrammable Spots Several strategically placed elements aim to create visually captivating ‘Instagrammable’ moments. The journey begins at the entry staircase, where a whimsical illustration introduces the cafe’s personality. Upon entering, a prominent neon light sign immediately catches the eye. Inside, a one-of-a-kind waffle mirror greets you at the entrance for your mirror selfies with your friends. Track lights are incorporated here to highlight specific areas, making them ideal for photos. “You will also find the neon lights in different spots around the cafe”, shares Architect Sheefa. The use of neon lights is an interior design trend in restaurants targeting younger crowds, particularly Gen Z. They create a visually appealing and Instagram-worthy atmosphere, making restaurants more attractive to social media-conscious customers, to create a unique and memorable visual experience. illustrations that speak to you To add character to the interiors, the beams and walls are filled with vibrant illustrations. In the beam above the counter, the illustrated characters resemble the target audience of the cafe, and how they interact and behave. Describing the artworks, Mashqurur Sabri, the artist, shares, “Nervosa walls are a burst of young energy and Dhaka madness — messy, loud, and full of heart. The hand-drawn, sketchy art style mixes raw lines with pops of bold, chaotic color — think warm reds, electric yellows, moody teals — capturing the city’s wild rhythm. From buzzing rickshaws to rooftop chill scenes, it’s the city on caffeine — vibrant, warm, and wide awake.” “When I think of Nervosa as perceived by the public, I wish it to be known as the most happening place in Siddeshwari,” says the owner, Sabeel Rahman. The vibrant interior, the playful name, and the strategic use of social media-friendly elements all point to a well-thought-out strategy. Nervosa isn’t just serving coffee; it’s serving an experience. And if the initial buzz is anything to go by, it’s an experience that Dhaka’s café-goers are eager to embrace. Written by Samira Ahsan

Read More