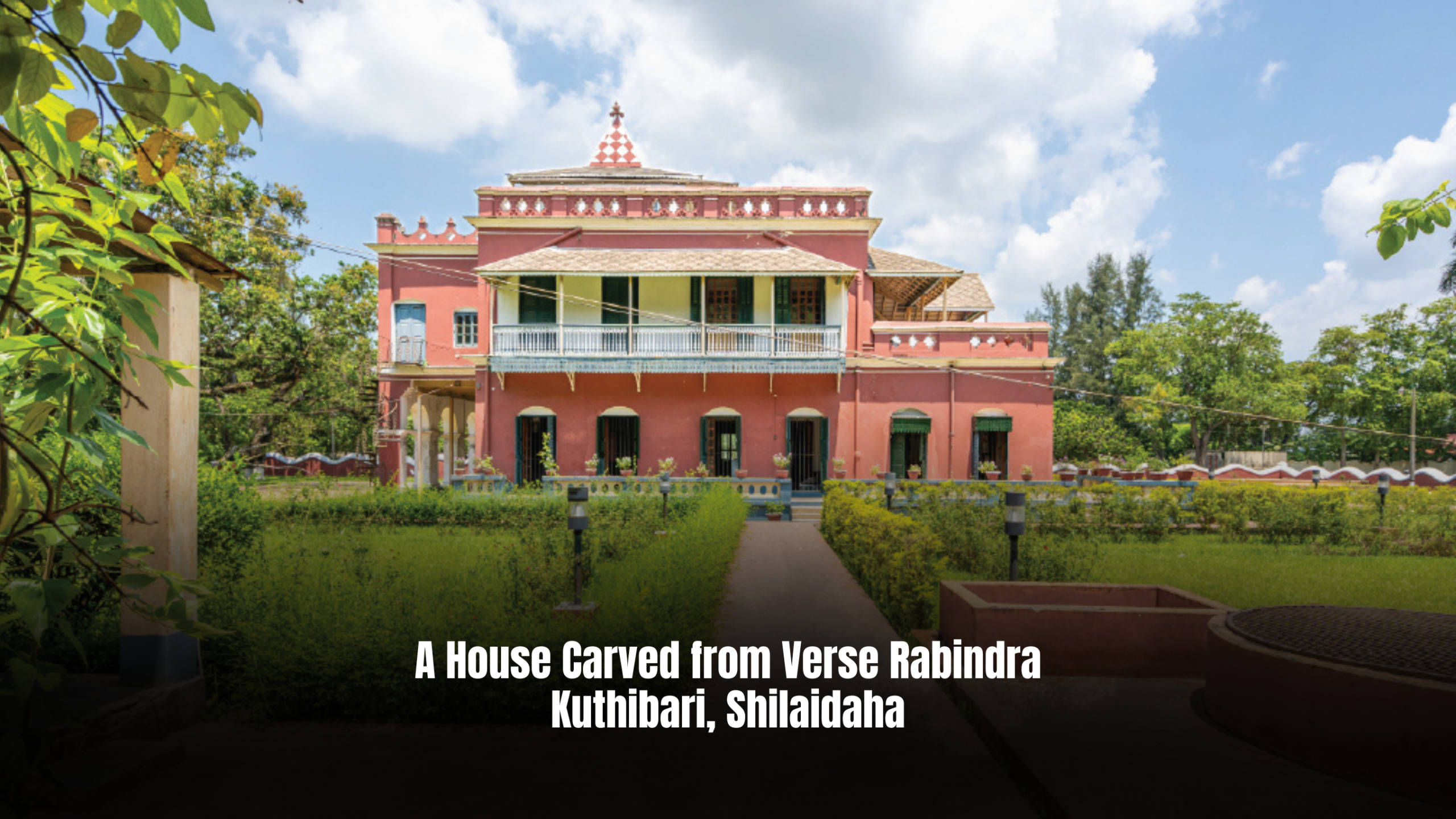

A House Carved from Verse Rabindra Kuthibari, Shilaidaha

In the quiet folds of Kushtia’s Kumarkhali upazila, just 20 kilometres away from the bustling town, stands a house that is not simply made of brick and timber—but of silence, river wind, and the rhythms of poetry. Rabindra Kuthibari, Shilaidaha, with its gentle red hue and pyramid-shaped roof, rises like a memory from the past. For those who follow the life and legacy of Rabindranath Tagore, this place is not just a historical site—it is a chapter from his soul. Long before the poet arrived, the land bore a different name—Khorshedpur. During the British colonial era, a European indigo planter named Shelly established a factory here. The convergence of the Gorai and Padma rivers created a swirling eddy nearby, a dah, which soon lent the village its new identity—Shellydaha. Over time, the name softened and reshaped itself into what it is today—Shilaidaha. It was in 1807 that Dwarkanath Tagore, Rabindranath’s grandfather, came into ownership of the estate through a will executed in his favour. And in the November of 1889, a young Rabindranath first arrived to take charge of his family’s zamindari. What was meant to be a duty, however, unfolded into something far deeper. Shilaidaha became the poet’s retreat, his muse, and his companion. Between 1891 and 1901, he stayed here on and off, and during those years, he wrote not only with discipline but with devotion. This house, nestled amidst orchards and ponds, framed by jackfruit and mango trees, heard the first lines of Sonar Tori, Chitra, Chaitali, and Katha O Kahini. The silence of the village, broken only by birdsong or boat horns on the river, gave birth to the songs of Gitanjali, fragments of Gitimalya, and most of Naibedya and Kheya. It was in this very setting, in 1912, that Rabindranath began translating Gitanjali into English. The poems—spiritual, meditative, and deeply intimate—were not just translations but transformations. In Shilaidaha’s peaceful stillness, words found a new cadence. By the time the English Gitanjali reached Europe, it was carrying the scent of Bengal’s riverbanks and the soul of this quiet estate. In 1913, this work earned him the Nobel Prize in Literature—making him the first non-European to receive this honour. But in many ways, the prize had already been won in these silent evenings spent under Shilaidaha’s sky. The house itself is unlike any ordinary zamindar residence. Built in the Indo-Saracenic style, the three-storied bungalow, with its sloping roofs made of Raniganj tiles and open balconies on every floor, seems more like a shelter for ideas than a place of power. Its walls, some say, were inspired by the gentle waves of the Padma River. Even now, though the Padma has changed its course and moved away, the spirit of the river lingers around the Kuthibari like a forgotten song still echoing in the wind. From its upper balcony, one could once see both the Padma and the Gorai flowing in opposite directions—a view so rare and sacred that it stirred the deepest parts of the poet’s being. Each morning, Rabindranath would sit by the window or wander into the yard, observing the life of villagers—their laughter, their burdens, their rhythms. From them, he drew characters, emotions, and philosophies. He often sat beside the pond under the shade of the Bakul tree, or climbed into his boat—the bajra—and let the wind on the Padma guide his thoughts. The poet did not write merely about the world; he wrote with the world. This house was no stranger to voices of genius. Friends and contemporaries from Bengal’s vibrant intellectual and cultural circles would gather here, filling the rooms with music, debate, laughter, and ideas that would shape the course of a generation. Among them were Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, whose revolutionary experiments in science had already gained acclaim, Dwijendralal Roy, the dramatist and composer whose patriotic songs stirred Bengal’s heart, and Promoth Chowdhury, whose essays and prose defined modern Bengali literature. Others like Mohitlal Majumdar and Lokendranath Palit also visited, finding in Shilaidaha both serenity and stimulation. These gatherings were not formal assemblies, but soulful retreats—quiet celebrations of art, knowledge, and the interconnectedness of all thought. The nostalgia of this place seeps through every doorframe. Even now, within the walls of the restored Tagore Memorial Museum, visitors stand before the poet’s bed, wardrobe, writing chest, and even the commode brought from England for his use. Each object whispers stories of a time when poetry lived here—not just on paper, but in the stillness between footsteps, in the rustle of mango leaves, in the soft splash of oars against water. The house is surrounded by an expanse of trees, some now older than memory itself. The flower garden continues to bloom seasonally, much like the poet’s verses—timeless and regenerative. Two buildings stand near the gate, named Gitanjali and Sonar Tari, housing a library, an auditorium, and an office. During the celebrations of Tagore’s birth and death anniversaries, the grounds come alive again—with music, recitations, and the mingling of hearts drawn to his legacy. Though the Padma has drifted away and the house no longer sees boats docking at its ghat, the essence remains unchanged. The wind still carries the same softness. The pond still holds reflections of a poet who once stood beneath a mango tree and wrote not just about Bengal, but for Bengal. Rabindra Kuthibari, Shilaidaha is more than a destination. It is a feeling—a pause in time. It is where literature took breath, where rivers became metaphors, and where Rabindranath Tagore found both solitude and song. For those who visit, it is not merely about seeing where he once lived. It is about walking into the pages of his life. Written by Samia Sharmin Biva