It began with a verdict. Not a speech, not a scandal—just a quiet ruling from Bangladesh’s judiciary. On June 5, 2024, the High Court reinstated a quota system for government jobs, reserving 56 percent of positions for specific groups, including descendants of freedom fighters. For many students, it felt like a door slamming shut.

Within days, campuses across the country stirred with frustration. The movement that followed—Students Against Discrimination—was born not in fury, but in resolve. Their rallies were orderly, their chants measured. But beneath the surface, tension simmered.

By early July, that tension boiled over. The protests evolved into the “Bangla Blockade,” a sweeping shutdown of roads and highways that paralysed the nation’s arteries. Buses vanished. Containers stacked up at ports. Supply trucks idled outside factories.

Dhaka’s markets emptied as perishables spoiled in the heat. Exporters missed deadlines. Small traders watched their earnings evaporate. What began as a student movement had metastasized into an economic crisis.

DEFINING MOMENTS

June 5 | 2024

High Court reinstates quotas

June 7-15 | 2024

Students begin peaceful rally, social media activism

July 01 | 2024

Nationwide Bangla Blockade begins

July 16 | 2024

Violent crackdown, leaving dozens killed

Late July | 2024

FDI approvals drop 40%; export delays, gas shortages

August 5 | 2024

Interim Government formed

Sep–Dec | 2024

Interest hits 10%; ADP spending 49-year low

Jan–Mar | 2025

Remittances peak; inflation eases; current account surplus

Apr–Jul | 2025

Recovery phase: DSEX up 12.5%; exports rebound; MFS grows 64%

August 5 | 2025 One-Year Anniversary

A Nation on Edge

On July 16 of 2024, the calm shattered. Security forces moved in with batons, tear gas, and live ammunition. The clashes were brutal. Ambulances raced through smoke-filled streets. Students lay bloodied on stretchers. Families camped outside police stations, desperate for news.

Independent monitors reported hundreds injured and dozens dead. The government disputed the numbers. But the images—broadcast across television screens and social media—left little room for doubt. The shockwaves were immediate.

Investor confidence collapsed. The Dhaka Stock Exchange saw its sharpest single-day drop in five years. Foreign direct investment approvals fell nearly 40 percent in the second half of 2024, according to the Dhaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry. The city, once buzzing with commerce, fell into a hush.

Three weeks later on August 5, an interim government was announced, led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus along with a panel of technocrats and civil society leaders. Their mandate: restore stability, rebuild trust, and prevent further economic unraveling.

The Economic Aftershocks

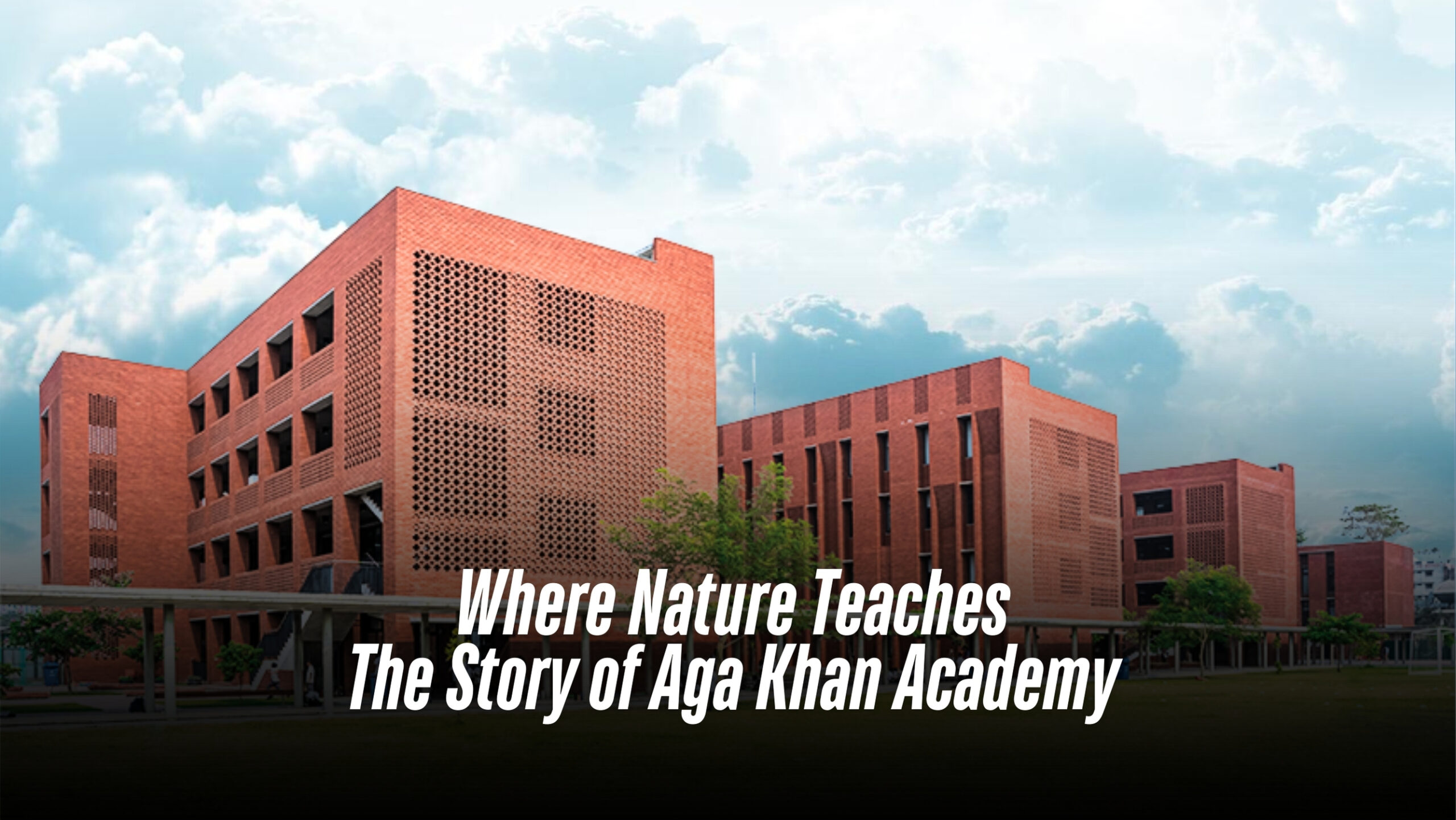

The July Uprising, as it came to be known, left no sector untouched. While the garment and ceramic sectors bore the immediate brunt, the ripple effects extended far wider.

The banking system, already strained by years of financial irregularities, teetered on collapse. A post-uprising asset quality review revealed widespread non-performing loans and misappropriated funds, prompting the interim government to initiate recovery drives and liquidity injections. The Bangladesh Bank raised the policy rate to 10 percent to tame inflation and stabilise the exchange rate.

Net foreign direct investment (FDI) dropped to a five-year low in 2024, as global investors cited political instability and opaque regulatory frameworks. The World Bank flagged Bangladesh’s deteriorating investment climate, while local chambers warned that the budget lacked a clear roadmap for restoring investor confidence.

The energy sector faced dual shocks: gas shortages crippled industrial output, while privatisation efforts triggered an 18 percent hike in urban electricity tariffs, sparking fresh protests.

The mental health toll was staggering. A Bangladesh Medical University seminar revealed that 82.5% of injured protesters suffered from depression, and 64% showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, underscoring the long-term human cost of the crisis.

In the ceramic industry, 70 factories struggled to stay afloat. The Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BCMEA) reported that gas pressure—critical for kiln operations—dropped to as low as 2 PSI in some zones, far below the required 15. Production stalled. Costs soared.

Their demands were precise: uninterrupted gas supply, priority allocation, compressor permissions, a five-year tariff freeze, and duty-free solar imports. None were met.

The garment sector fared no better. The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) confirmed shipment delays averaging two weeks during the unrest.

Export Promotion Bureau (EPB) data showed a 7.8% decline in garment exports in Q3 of 2024. Buyers in Europe and North America have shifted orders to Vietnam and India. Smaller exporters faced penalties and lost contracts, according to the Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA).

The Foreign Investors’ Chamber of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) called for stronger rule of law, faster customs clearance, and smoother approvals. The Bangladesh Chamber of Industries (BCI) highlighted the plight of agro-processors, many of whom faced wastage and layoffs. Their appeal: concessional loans and tax relief.

Even real estate, long seen as a safe haven, stumbled. The Real Estate and Housing Association of Bangladesh (REHAB) reported a sharp drop in property transactions, citing high registration fees, interest rates, and uncertainty over the Detailed Area Plan (DAP) revisions.

Across industries, the message converged: without urgent reform, Bangladesh’s hard-earned gains risked slipping away.

The Numbers Behind the Crisis

The numbers told a sobering story. By late 2024, exports faltered, imports shrank, and growth slowed to its weakest pace in years. The disruptions that began with student protests soon seeped into every corner of the economy, from factories to food markets.

Inflation surged through the summer, eroding wages and squeezing households already under strain. Though the pace of price rises eased the following year, the scars remained.

Construction sites went quiet, housing demand collapsed, and long-promised infrastructure projects were postponed. The slowdown was no longer abstract—it showed in half-finished bridges and shuttered shops.

Private investment also lost its footing. Business registrations dwindled, banks groaned under bad loans, and confidence withered. Even as revenue collection improved, it could not disguise the broader fragility.

Yet, amid the gloom, unlikely lifelines emerged. Migrant workers sent record remittances, keeping families afloat and rural markets alive. These inflows allowed the central bank to rebuild reserves and offered a measure of currency stability.

Exports regained momentum too, showing the grit of industries used to hardship, though manufacturers warned that impatient buyers were already shifting orders abroad.

The trade balance improved, but mostly for the wrong reasons—families buying less, businesses importing little, demand simply suppressed. Economists called it a fragile equilibrium, held together more by restraint than strength.

The human toll was heavier still. Around 1,400 people were killed during the July 2024 uprising in Bangladesh, according to a fact-finding report by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

During this time, media reports say, thousands more were injured or arrested, leaving families shattered and communities scarred. Poverty climbed sharply, dragging millions back below the line.

And yet, signs of resilience flickered. The stock market rebounded, foreign investors edged back, and the currency steadied. Still, experts warned that numbers alone could not restore trust.

The UN’s February 2025 report pressed for international-standard trials of July’s atrocities, warning that without justice, foreign cooperation—and lasting recovery—would remain elusive.

Policy Response

The interim government moved quickly. Bangladesh Bank introduced new routines for reviewing monetary policy and set clear targets for money supply and foreign assets. Support for trade credit and export finance was expanded. Liquidity risks in banks were monitored closely.

To strengthen remittance inflows, the central bank launched incentives for formal channels, including fee waivers and digital onboarding. Data was published openly to build public trust.

On the social front, safety-net programmes were expanded with World Bank support. A new scheme was designed to improve cash transfer targeting, ensuring vulnerable households received timely relief.

Infrastructure also saw renewed focus. The Bay Terminal project in Chattogram, long delayed, was fast-tracked with international financing. The terminal aims to expand container capacity and reduce ship handling times—critical for keeping export shipments on schedule.

By mid-2025, signs of stabilisation emerged. Inflation cooled. Remittances remained strong. The trade balance showed early improvement. But analysts warned that recovery would depend on more than numbers. Confidence—in markets, in governance, in the rule of law—had to be rebuilt.

Lessons from the Uprising

The July protests began with a single decision: the reinstatement of quotas in public service recruitment. But what followed was not just a reaction to policy—it was a reflection of deeper frustrations.

Students and young professionals felt betrayed. When the rules changed, it felt like the system had turned its back on them.

The government’s response—swift arrests, silence, and force—only deepened the anger. What started as a demand for fairness became a broader call for accountability.

Cracks Beneath the Surface

The unrest exposed weaknesses in Bangladesh’s economic structure. The country has been leaning heavily on garments and remittances. When those sectors faltered, the impact was immediate.

The gas shortage that followed crippled factories, disrupted supply chains, and sent shockwaves through export markets. The crisis didn’t create these problems—it revealed them.

The Cost No One Talks About

Beyond the economic fallout, the human cost was profound. Many protesters were injured. Some lost jobs. Others are still dealing with trauma.

A country cannot move forward if its youth are left behind—physically, emotionally, or economically. Mental health support, long neglected in public policy, must now be part of any serious recovery plan.

The World Was Watching

The international response was swift and sobering. Investors pulled back, citing instability and uncertainty. Human rights groups raised alarms. The United Nations called for trials and reforms.

Bangladesh’s reputation took a hit—not just because of the unrest, but because of how it was handled. Restoring trust will require more than economic recovery. It will require institutional maturity.

Recovery Isn’t Enough

Today, some indicators are improving. Exports are rising again. Inflation is easing. Remittances are flowing. But recovery built on emergency measures and short-term fixes is fragile. True resilience means building systems that can withstand pressure—strong local governance, steady policies, and safety nets that don’t collapse in a crisis.

A Chance to Rethink the Future

Experts have called for diversification, infrastructure investment, and tax reform. These are important steps. But the deeper lesson from the uprising is philosophical: growth must serve people, not just numbers.

The July protests were painful. But they also offered a rare moment of clarity. They showed what happens when people feel unheard. And they reminded the nation that progress is not just about GDP—it’s about dignity, fairness, and the promise of a better tomorrow.

Written by Shoyeb Rehaan