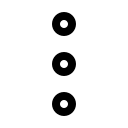

Dissonance Of Debris

From May 17th to 31st, the solo painting exhibition titled “Debris” by Kazi Salahuddin Ahmed adorned the walls of La Galerie, Alliance Française de Dhaka, Dhanmondi. The two-week-long, thought-provoking exhibition featured nearly 30 works on board paper, providing spectators with a glimpse into the artist’s most recent studies. Remembering is a kind of rebellion in Kazi Salahuddin Ahmed’s universe. His solo exhibition, “Debris,” was an uncompromising documentation of human vulnerability. The artist’s recollections of Bangladesh’s 1971 Liberation War seep into modern tragedies—Gaza’s annihilation, the Rohingya exodus, and Kashmir’s stifled cries. The paintings didn’t merely show ruins; they also resurrected spirits. Ahmed’s life had several eras of turmoil. Born within a world transformed by partition and war, his early work in the 1980s was abstract, but the twenty-first century tightened his emphasis. The song “Debris” captures this progression. Each piece is a palimpsest, with layers of pigment representing the strata of history, where erasure and evidence fight silently. Ahmed’s use of board paper as canvas makes a statement in and of itself. Board paper repels, as opposed to ordinary canvas, which absorbs, forcing the artist to handle surface tension. The resulting sculptures have a temporary quality, as if they would disintegrate like the makeshift shelters in Cox’s Bazar’s refugee camps. Though anchored in Bangladeshi stories, “Debris” speaks to a lexicon of global migration. The exhibition’s centerpiece, “Babel Fragment” (2024), depicts the mythological tower as a jagged silhouette against a sulfurous hue. Its shattered planes evoke both bombed-out Aleppo and the decaying tenements of Old Dhaka. Ahmed, who has flown from Paris to Islamabad, appears to imply that rubbish knows no boundaries. In “Eclipse of Return” (2024), a skeletal stairway rises into the emptiness, its steps fractured like vertebrae. Nearby, “Archive of Dust” displays a child’s sneaker half-buried in a thick texture that mimics charred dirt “The utter erasure of Gaza, which was once full of life; the ongoing miseries of people in Kashmir; or the hopelessness faced by displaced Rohingyas attempting to make a living in camps in Chattogram—all of this jostles the mind as one attempts to ponder the future of the human race. Furthermore, it is difficult to leave behind the legacy of Bangladesh’s repeated failures to shape a future. The people’s desire for political stability has always been a never-fulfilled dream in our country. The demise of the authoritarian dictatorship has undoubtedly allowed everyone to focus on a future beyond the current system, but it appears that things are still breaking apart, leaving us with only emotional rubble,” observed famous art critic Mustafa Zaman. The intimacy of “Debris” sets it apart from other forms of protest art. In “Letters Unsent,” bits of Urdu and Bangla letters emerge behind layers of gray, like voices muted by time. The piece is similar to Ahmed’s 2018 series on refugee diaries, but the language is virtually illegible—a metaphor for history’s selective memories. Written By Shahbaz Nahian

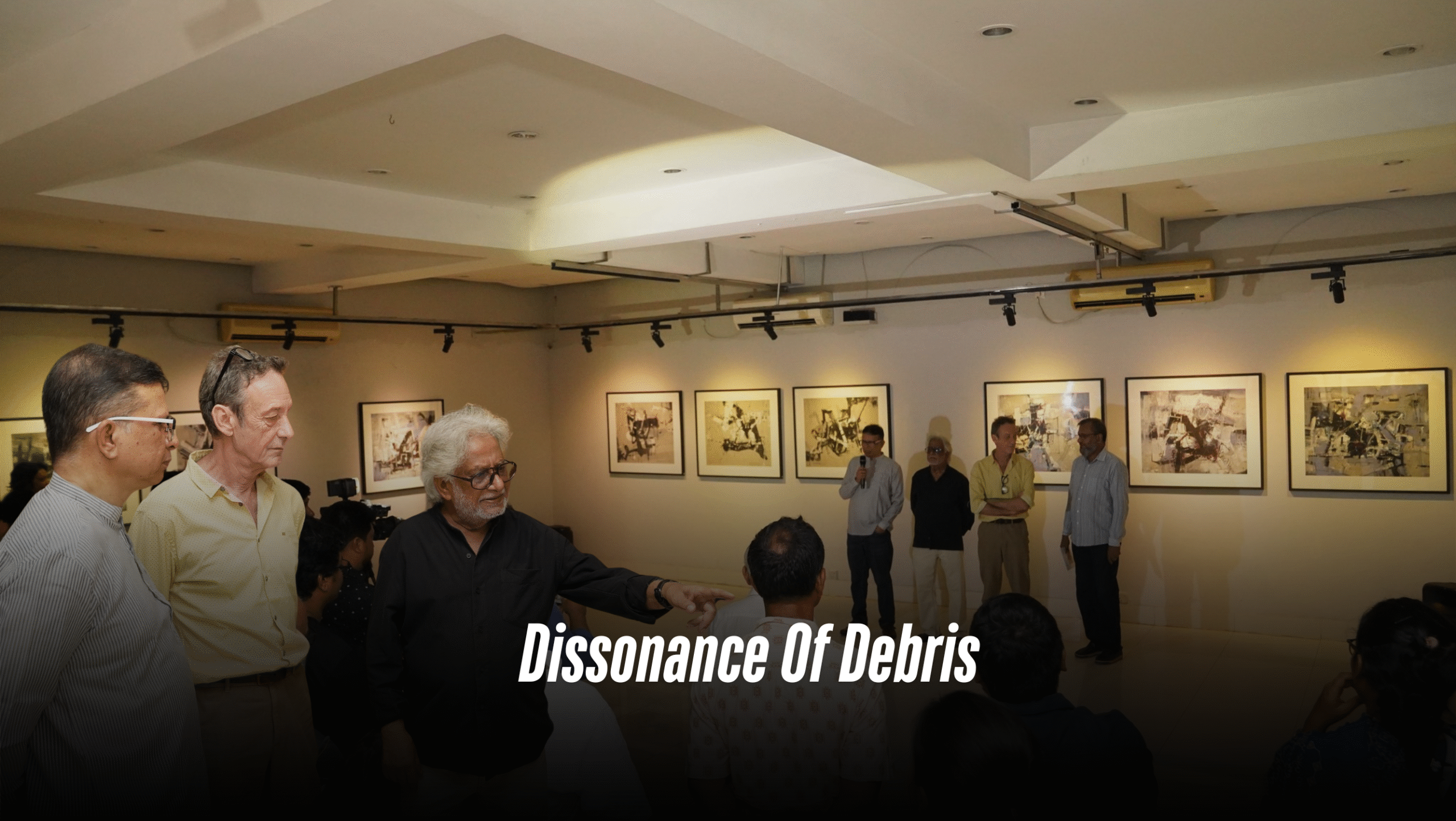

Reviving the Roots: Conservation & Restoration Progress Reflections by Conservation Architect Abu Sayeed M Ahmed

At the anniversary celebration of Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine, esteemed conservation architect and heritage specialist Abu Sayeed M Ahmed presented “Reviving the Roots: Conservation and Restoration Progress”—a heartfelt journey through two decades of architectural conservation across Bangladesh. With vivid images and powerful anecdotes, he reminded the audience that conservation is not about romanticising ruins—it is about safeguarding identity, craftsmanship, and cultural continuity in a nation at risk of forgetting itself. “Every day in Dhaka, a piece of our heritage vanishes. Buildings are bulldozed in the name of development. But without roots, how can we grow a future that is truly ours?” Bringing History Back to Life Nimtali Deuri & Naib-Nazim Museum, Dhaka Abu Sayeed M Ahmed’s first major restoration was the late Mughal-era Nimtali Deuri in Old Dhaka. Hidden under layers of plaster. The restored gateway now houses the Naib-Nazim Museum, commemorating the deputy governors of Dhaka and reflecting a revived connection between the city and its Mughal past. Uttar Halishahar Mosque, Chattogram This 200-year-old mosque was facing demolition for modern expansion. Upon assessment, its authentic Mughal character became evident. Abu Sayeed’s team removed inappropriate cement layers, dismantled an added veranda, and re-clad it in traditional lime and surki. Locals now call it a “Gayebi Mosque”—as if it reappeared by miracle. Nearby, a new mosque by Architect Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury respectfully contrasts the old, echoing its jali motifs in modern concrete. Hanafi Jame Mosque, Keraniganj Once a modest family-owned mosque, it gained global recognition after restoration—winning a UNESCO Award. A new mosque built adjacent to it by Architect Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury, with full visibility of the old structure—offers a striking example of architectural dialogue between past and present, tradition and transparency. Rediscovering Rural Heritage Buraiich Maulvi Bari, Faridpur Neglected and engulfed by vines, this ancestral home seemed destined for ruin. Through sensitive restoration, it has been transformed into a heritage Airbnb, preserving its traditional character while offering economic sustainability. Period furniture, handpicked materials, and contextual storytelling give visitors a window into Bengal’s rural past. Mithamoin Kachari Bari, Kishoreganj This decaying administrative house—once thought beyond repair—was restored to reflect its original civic purpose. From a wild, overgrown ruin, it emerged as a dignified reminder of regional governance and colonial-era architecture, now serving as an active public building. Urban Civic Revival Narayanganj Municipal Building Among Bangladesh’s earliest municipal structures, it was at risk of being replaced. A dual solution—preserve the old and integrate it into the new. Today, it functions as the entrance to the new Nagar Bhaban (City Hall), and plans are underway to convert its upper level into a civic museum. Baro Sardar Bari, Sonargaon A Mughal-Colonial mansion from the Baro-Bhuiyan era, this structure was revived through corporate social responsibility. South Korea-based Youngone Corporation led the project under the leadership of CEO Kihak Sung, who has familial roots in the region. This model highlights how private sector investment can play a crucial role in cultural restoration. Reviving Lost Icons Dhaka Gate (Mir Jumla Gate) Once a neglected and overgrown monument, the historic city gate has been revitalised with its original grandeur—complete with a replicated fire cannon that signals its defensive legacy. Rose Garden Palace, Tikatuli, Dhaka A jewel of Dhaka’s architectural heritage, the Rose Garden was meticulously restored—from stained-glass panels to ornamental plasterwork. Where pieces were missing, they were reconstructed based on archival records, ensuring authenticity over imitation. Hammam Khana, Lalbagh Fort Perhaps the most complex restoration, the Mughal-era bathhouse had suffered colonial and post-colonial misuse. Funded by the U.S. Ambassador’s Fund, the project uncovered a breathtaking pavilion structure, restored lighting from above (true to hammam tradition), and reestablished the original spatial and sensory quality of the Mughal bathhouse. Crafting the Future with the Past Reviving Chini Tikri Ornamentation A rare local tradition, Chini Tikri—the use of broken ceramic dinnerware to form decorative motifs—was resurrected. The team digitally reconstructed patterns, reproduced the plates, broke them and reapplied them by hand. This craft was even adapted into a contemporary mosque in Noakhali, designed by Architect Mamnoon Murshed Chowdhury and Architect Mahmudul Anwar Riyaad, using waste ceramic products donated by Monno Ceramics. These projects demonstrate what is possible when craftsmanship, community, and conservation come together. They are not just restorations—they are cultural revivals, offering spaces where memory, faith, and identity continue to live. Written by Samia Sharmin Biva

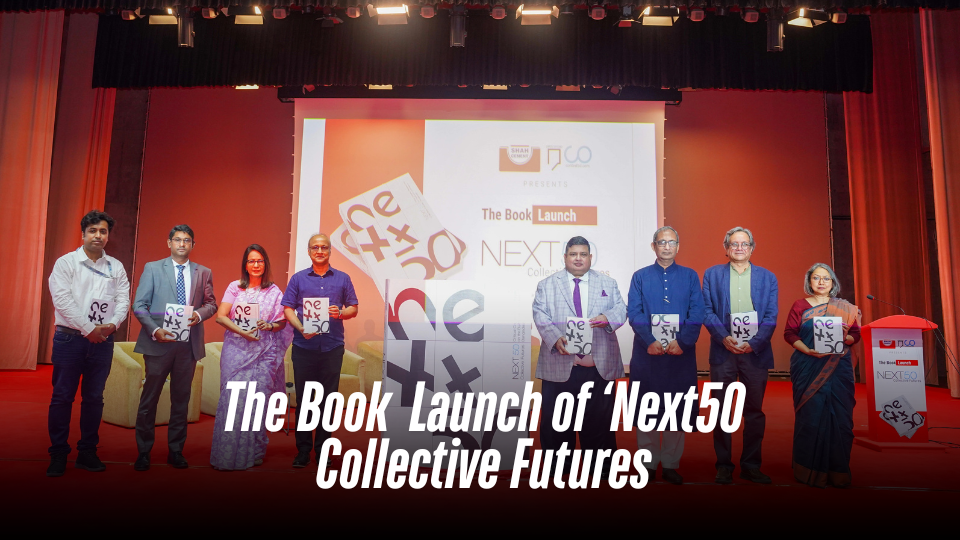

The Book Launch of ‘Next50: Collective Futures

A significant milestone in shaping Bangladesh’s future was marked today with the official launch of Next50: Collective Futures at BRAC University’s Multipurpose Hall. This landmark publication—the largest edited volume on Bangladesh’s built environment—brings together 81 authors, including many from the Bangladeshi diaspora, to explore the nation’s next five decades of progress, innovation, and connectivity. Spanning 49 chapters across nine major themes, the book examines urban and rural transformation, infrastructure, climate resilience, housing, governance, and technological innovation. Written in accessible language for policymakers, practitioners, and the general public, it bridges cutting-edge research with real-world impact, making complex ideas actionable for those shaping the nation’s future. The event was attended by some of Bangladesh’s most prominent architects, planners, and urbanists from both academia and professional practice. Distinguished guests included Dr. Syed Ferhat Anwar, Vice-Chancellor of BRAC University, and Mohammad Azaz, Administrator of Dhaka North City Corporation, who underscored the urgency of visionary thinking in driving sustainable and inclusive development. The program featured a compelling book introduction by Professor Fuad H. Mallick, Editor-in-Chief of Next50 and Dean of the School of Architecture and Design at BRAC University, followed by an insightful review from Dr. Mohammed Zakiul Islam, Professor at BUET, who highlighted the book’s interdisciplinary approach and its relevance to Bangladesh’s rapidly evolving urban landscape. Adding to the discussions, key stakeholders, including representatives from Shah Cement, reflected on the private sector’s role in shaping the built environment. The event concluded with remarks from the book’s executive editors, Dr. Tanzil Shafique and Dr. Saimum Kabir, who emphasized the collaborative effort behind the publication and its potential to influence future policies and practices. Shah Cement also expressed interest in future collaborations. Beyond the discussions, the launch served as a key networking platform for scholars, policymakers, and industry leaders, fostering dialogue and collaboration on the country’s long-term development. Attendees engaged in meaningful conversations over Iftar and dinner, reinforcing the event’s role in strengthening professional and intellectual ties. Organized by Open Studio and Context BD, with support from Shah Cement, the event also reached a wider audience through a live stream, ensuring broader engagement with the book’s mission.