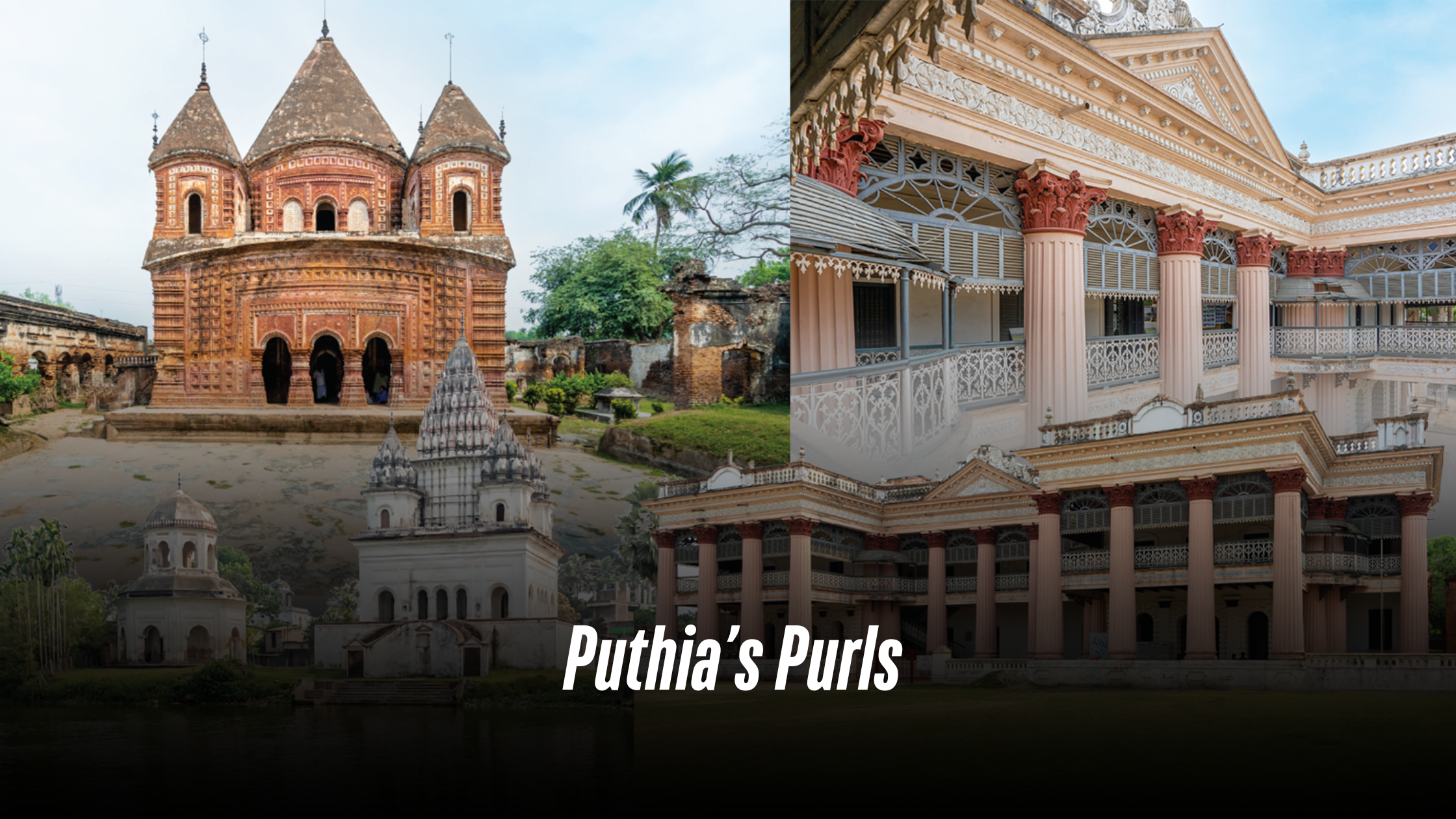

Nestled in northern Bangladesh in the heart of Rajshahi, the Puthia Rajbari (Palace) Complex stands as a vivid reminder of the region’s storied past. This captivating ensemble of temples and palaces—set against a backdrop of tranquil water bodies and lush greenery—offers visitors a rare glimpse into the majesty of Bengal’s bygone eras

Puthia’s rise to prominence dates back to the late 16th century, evolving by the 18th century into a bastion of wealth and influence. Originally part of the Laskarpur Pargana and named after Laskar Khan Nilamber—the brother of the first zamindar, who earned the title of Raja from Mughal Emperor Jahangir—the estate underwent a significant division in 1744. This partition split the zamindari into four co-shares, with the Panch Ani (five annas) and Char Ani (four annas) shares emerging as particularly influential. The Panch Ani estate, skillfully managed by Maharani Sarat Sundari and Maharani Hemanta Kumari, became celebrated for its efficient administration and enthusiastic patronage of the arts.

In 1895, Maharani Hemanta Kumari Devi commissioned the construction of the two-storied Puthia Rajbari—an architectural marvel dedicated to her mother-in-law, Maharani Sarat Sundari Devi. A fine example of Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture, the palace harmoniously blends European neoclassical ideals with indigenous Bengali design.

Strategically located along the Rajshahi–Natore highway (approximately 30 km east of Rajshahi town and 1 km to its south), the palace is surrounded by protective ditches and sprawls over 4.31 acres. It is organized into four distinct courts: the Kachhari (office) courtyard, the Mandir Angan or Gobindabari (temple court), the Andar Mahal (private quarters), and the residence of Maharani Hemanta Kumari Devi. Today, the palace also functions as a museum, offering insights into the rich tapestry of Puthia’s history.

Under British colonial rule, the Puthia family continued to play a pivotal role in Bengal’s governance. Eager to integrate local elites into their administrative framework, the colonial authorities relied on influential zamindars such as the Puthia royals. This collaboration enhanced their economic wealth and social standing while cementing Puthia’s reputation as an architectural and cultural beacon during the 19th century—a remarkable melding of Mughal elegance with European influences that produced a unique heritage.

The palace rooms are arranged around several courts, all of which are single-storeyed except for the Kachari Angan. This section features Palladian porticos with four semi-Corinthian columns on both the western and eastern ends—one leading to the Kachari Angan and the other to the Temple (Gobindabari) courts. The porticos and central section include arcaded loggias on the first floor, while a wooden staircase on the east side ascends to three varied rooms (two of which once served as treasuries) on one side and four rooms with verandahs on the other. The northern block is double-storeyed, with a wide hall measuring 21.95 m x 7.16 m, a verandah with side balconies, and six additional rooms upstairs. In the Andar Mahal, the western section comprises two rooms and several bathrooms, while the eastern section houses a one-storeyed residence of Rani Hemanta Kumari. This residence includes a porch, a central reception hall with nine rooms, extended arch-adorned verandahs, and a roof supported by iron and wooden beams. Overall, the palace primarily served as the administrative and residential hub of the Puthia estate.

The complex is also home to several iconic temples that epitomize its architectural grandeur: Bhubaneshwar Shiva Temple (1823): Constructed by Rani Bhubonmoyee Devi, this temple is the largest Shiva temple in Bangladesh. Built in the Pancha Ratna (five-spired) style, it enchants visitors with intricate stone carvings and houses a massive black basalt Shiva Linga—the largest of its kind in the country.

Govinda Temple: Erected in the mid-19th century by the queen of Puthia and dedicated to Lord Krishna, this temple is famed for its exquisite terracotta ornamentation. Its five imposing spires, detailed with depictions of divine figures, epic battles, and mythological narratives, showcase the fervor and artistic talent of the region.

Jagannath Temple: In a striking departure from conventional designs, this two-storied octagonal temple—dedicated to Lord Jagannath—features four pillars crowned with domes. Its unconventional shape highlights the infusion of European neoclassical elements into traditional local design.

Chauchala Chhota Govinda Mandir: Dating to the late 18th or early 19th century, this temple adheres to the Char Chala style, characterized by its distinct four-cornered roof. Its terracotta façade vividly narrates rich tales from Hindu mythology, including cosmic battles between gods and demons.

Bara Anhik Mandir: Representing an intriguing fusion of styles, this temple combines a central two-chala structure with two flanking four-chala wings—a rare architectural combination scarcely seen elsewhere in Bangladesh.

Choto Shiv Mandir: Tucked behind the Rajbari, this humble yet finely crafted temple exemplifies the refined skills of Bengal’s artisans and provides a serene retreat for those seeking a private space for reflection.

As Bengal’s social and political landscapes evolved under British influence, complexes like Puthia became more than centers of worship—they grew into symbols of local identity. The sacred grounds of the Puthia Temple Complex evoke an era when devotion, artistic brilliance, and effective governance merged to create a legacy that continues to inspire awe. Even amid challenges such as the Bangladesh Liberation War and other periods of political upheaval, dedicated preservation efforts by local authorities and heritage organizations have maintained the complex’s original splendor.

In safeguarding its stone and clay, they preserve not merely a collection of monuments but a living cultural heritage that speaks volumes about the spirit of Bengal.

Exploring Puthia’s legacy invites further discovery—from delving into the nuanced artistic details of terracotta carvings to understanding how colonial and indigenous influences converged to shape regional identity. This complex remains a beacon for

anyone passionate about history, art, and the enduring human endeavor to immortalize culture through architecture.