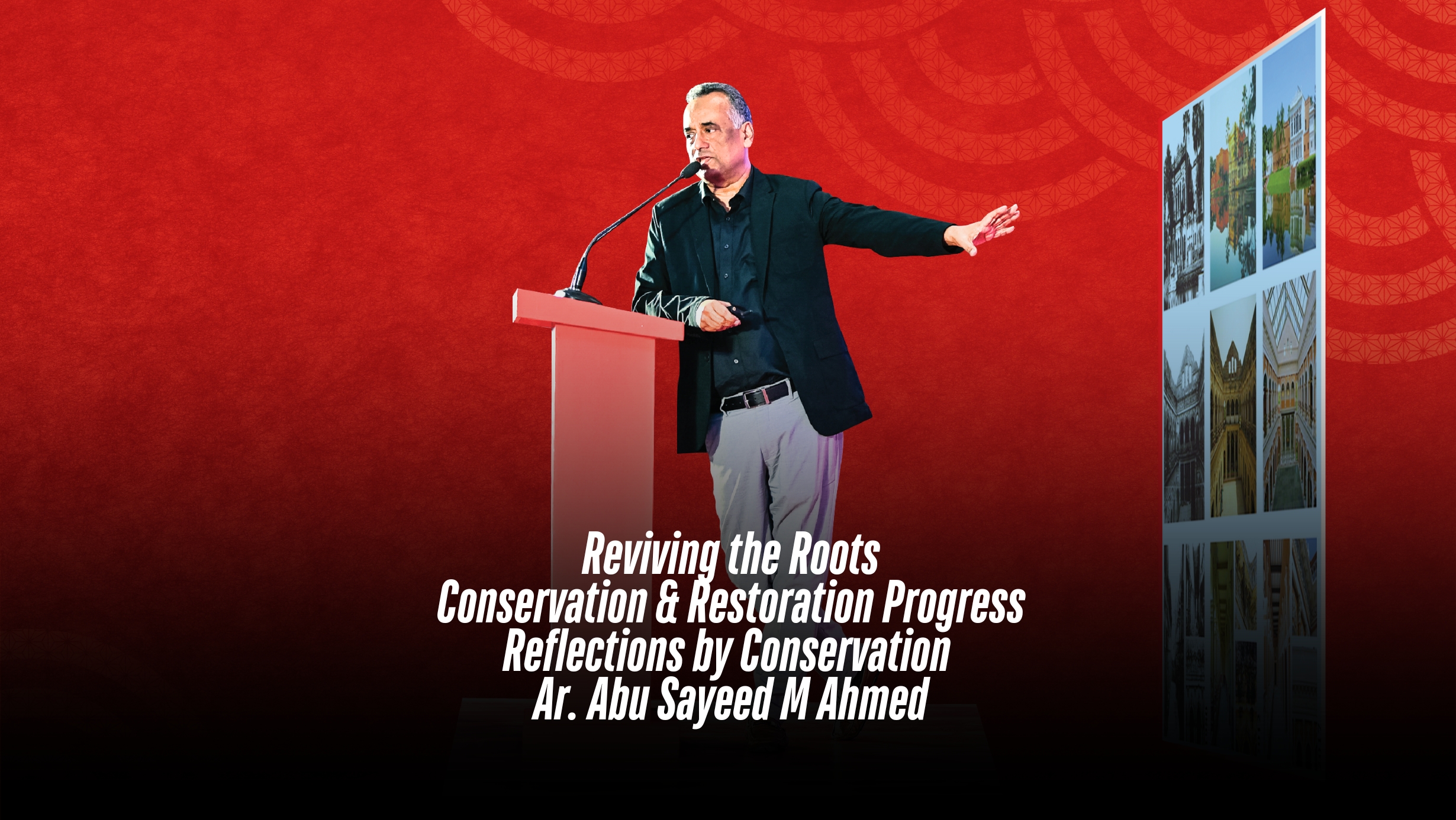

At the anniversary celebration of Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine, esteemed conservation architect and heritage specialist Abu Sayeed M Ahmed presented “Reviving the Roots: Conservation and Restoration Progress”—a heartfelt journey through two decades of architectural conservation across Bangladesh. With vivid images and powerful anecdotes, he reminded the audience that conservation is not about romanticising ruins—it is about safeguarding identity, craftsmanship, and cultural continuity in a nation at risk of forgetting itself.

“Every day in Dhaka, a piece of our heritage vanishes. Buildings are bulldozed in the name of development. But without roots, how can we grow a future that is truly ours?”

Bringing History Back to Life

Nimtali Deuri & Naib-Nazim Museum, Dhaka

Abu Sayeed M Ahmed’s first major restoration was the late Mughal-era Nimtali Deuri in Old Dhaka. Hidden under layers of plaster. The restored gateway now houses the Naib-Nazim Museum, commemorating the deputy governors of Dhaka and reflecting a revived connection between the city and its Mughal past.

Uttar Halishahar Mosque, Chattogram

This 200-year-old mosque was facing demolition for modern expansion. Upon assessment, its authentic Mughal character became evident. Abu Sayeed’s team removed inappropriate cement layers, dismantled an added veranda, and re-clad it in traditional lime and surki. Locals now call it a “Gayebi Mosque”—as if it reappeared by miracle. Nearby, a new mosque by Architect Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury respectfully contrasts the old, echoing its jali motifs in modern concrete.

Hanafi Jame Mosque, Keraniganj

Once a modest family-owned mosque, it gained global recognition after restoration—winning a UNESCO Award. A new mosque built adjacent to it by Architect Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury, with full visibility of the old structure—offers a striking example of architectural dialogue between past and present, tradition and transparency.

Rediscovering Rural Heritage

Buraiich Maulvi Bari, Faridpur

Neglected and engulfed by vines, this ancestral home seemed destined for ruin. Through sensitive restoration, it has been transformed into a heritage Airbnb, preserving its traditional character while offering economic sustainability. Period furniture, handpicked materials, and contextual storytelling give visitors a window into Bengal’s rural past.

Mithamoin Kachari Bari, Kishoreganj

This decaying administrative house—once thought beyond repair—was restored to reflect its original civic purpose. From a wild, overgrown ruin, it emerged as a dignified reminder of regional governance and colonial-era architecture, now serving as an active public building.

Urban Civic Revival

Narayanganj Municipal Building

Among Bangladesh’s earliest municipal structures, it was at risk of being replaced. A dual solution—preserve the old and integrate it into the new. Today, it functions as the entrance to the new Nagar Bhaban (City Hall), and plans are underway to convert its upper level into a civic museum.

Baro Sardar Bari, Sonargaon

A Mughal-Colonial mansion from the Baro-Bhuiyan era, this structure was revived through corporate social responsibility. South Korea-based Youngone Corporation led the project under the leadership of CEO Kihak Sung, who has familial roots in the region. This model highlights how private sector investment can play a crucial role in cultural restoration.

Reviving Lost Icons

Dhaka Gate (Mir Jumla Gate)

Once a neglected and overgrown monument, the historic city gate has been revitalised with its original grandeur—complete with a replicated fire cannon that signals its defensive legacy.

Rose Garden Palace, Tikatuli, Dhaka

A jewel of Dhaka’s architectural heritage, the Rose Garden was meticulously restored—from stained-glass panels to ornamental plasterwork. Where pieces were missing, they were reconstructed based on archival records, ensuring authenticity over imitation.

Hammam Khana, Lalbagh Fort

Perhaps the most complex restoration, the Mughal-era bathhouse had suffered colonial and post-colonial misuse. Funded by the U.S. Ambassador’s Fund, the project uncovered a breathtaking pavilion structure, restored lighting from above (true to hammam tradition), and reestablished the original spatial and sensory quality of the Mughal bathhouse.

Crafting the Future with the Past

Reviving Chini Tikri Ornamentation

A rare local tradition, Chini Tikri—the use of broken ceramic dinnerware to form decorative motifs—was resurrected. The team digitally reconstructed patterns, reproduced the plates, broke them and reapplied them by hand. This craft was even adapted into a contemporary mosque in Noakhali, designed by Architect Mamnoon Murshed Chowdhury and Architect Mahmudul Anwar Riyaad, using waste ceramic products donated by Monno Ceramics.

These projects demonstrate what is possible when craftsmanship, community, and conservation come together. They are not just restorations—they are cultural revivals, offering spaces where memory, faith, and identity continue to live.