Dhaka’s wheel

The rickshaw is the quintessential three-wheeler of Dhaka. If one were to encapsulate the spirit of the city with a single vehicle, it would undoubtedly be the rickshaw. Even in an era dominated by modern transport and ride-hailing services, the rickshaw remains a beloved tradition. Riding in a rickshaw, one can experience a serene immersion in nature—a reflective calm—despite the bustling chaos of Dhaka outside.

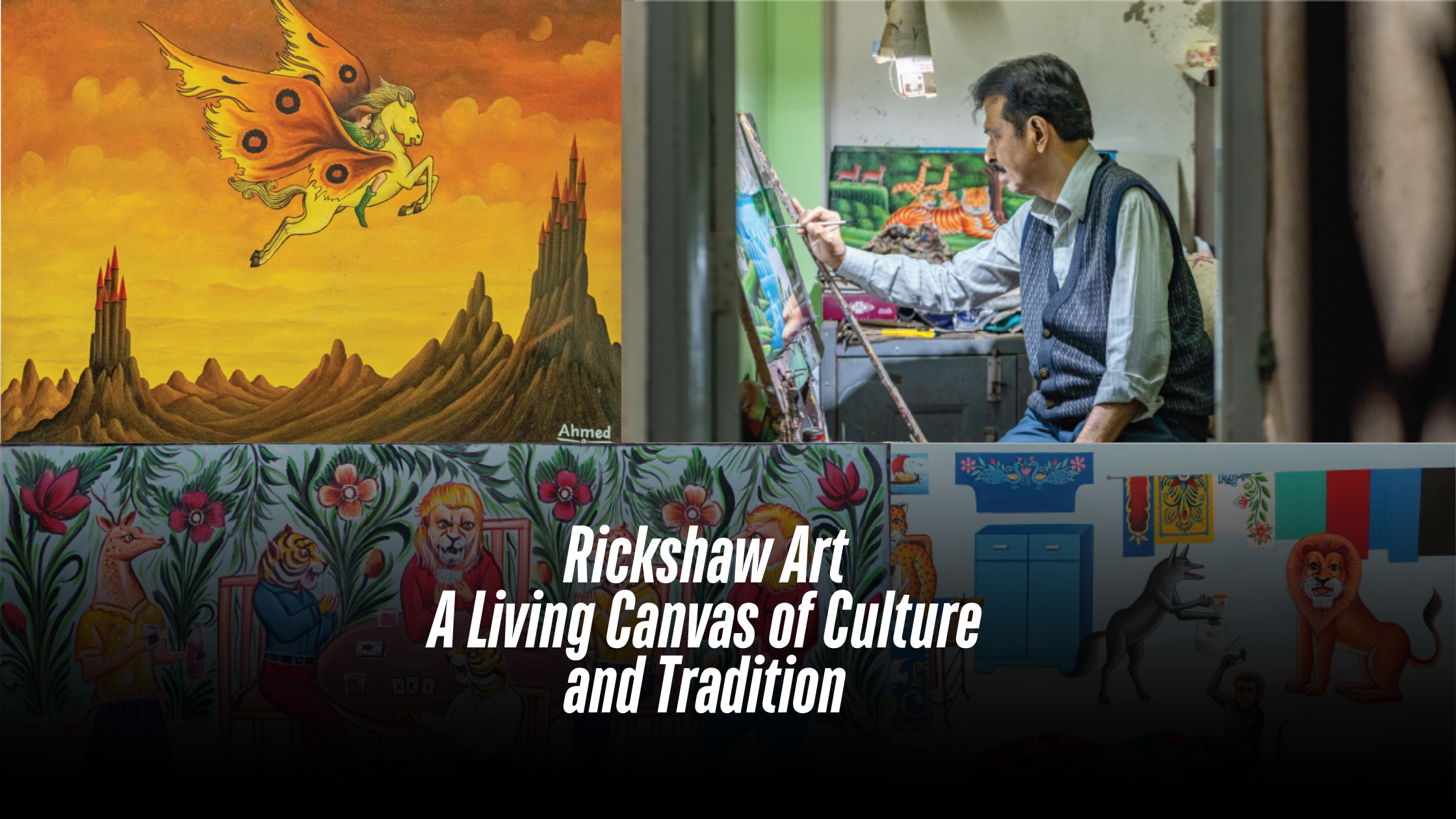

More than a means of transport, rickshaws are mobile masterpieces. Handcrafted by skilled artisans, they feature oil paintings adorned with vibrant floral patterns, birds, animals, movie stars, and scenes from folk tales, effectively transforming the streets into a roving gallery. On December 6, 2023, UNESCO recognized Bangladesh’s rickshaw art as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity—a distinction that has gripped global attention and sparked renewed domestic interest. Galleries across the country are now hosting exhibitions to celebrate this unique cultural tradition.

History throughout

The three-wheeled rickshaw has been a part of Bangladeshi life since the 1940s. By the late ‘40s, decorative elements such as movie star portraits and intricate floral designs began to appear, heralding the birth of what is now known as rickshaw art. Originating in Rajshahi and Dhaka, this art form evolved with each district contributing its own unique stylistic influences.

Artist Syed Ahmad Hossain has been a devoted practitioner of rickshaw art since 1969. A self-taught talent, his works have not only graced exhibitions around the world but also served as a visual chronicle of his era. During the Liberation War, for instance, he vividly captured scenes of conflict on rickshaws, transforming them into moving narratives of historical events.

In 1975, political unrest led to fears of a ban on rickshaw painting, prompting many artists—including Syed—to shift their focus to signboard painting. Concurrently, rising religious sensitivities rendered the portrayal of human faces and film scenes controversial, ushering in a new era where artists gravitated toward universally acceptable subjects such as trees, animals, and nature. Gradually, human faces were replaced with symbolic imagery that communicated profound stories without uttering a single word.

Syed recalls a time when cheap, mass-produced prints of rickshaw art flooded the market, selling for merely 60–70 taka. Although these replicas lacked the detail and artistry of the originals, their affordability made them popular. This oversaturation, however, contributed to a devaluation of authentic rickshaw art.

During Pohela Boishakh, rickshaw art transforms from vehicle decoration into a marketable commodity. Artisans create posters, canvas prints, postcards, and figurines that feature iconic rickshaw designs; these items are cherished as souvenirs, home décor, or thoughtful gifts. Such initiatives underscore the collective effort required to preserve and celebrate this cultural tradition.

Wheels got heavier!

Today, the art of hand-painted rickshaws teeters on the brink of extinction. The rise of motorized rickshaws—lacking the space for detailed artwork—and the advent of digital printing have contributed to its decline. With only a few traditional rickshaw artists remaining, there is growing concern that this vibrant form of pop art may be lost.

Innovative artists are finding new expressions for rickshaw art beyond the vehicles themselves. Syed, for example, has successfully translated this living art onto handcrafted items like hurricane lamps, trunks, and portraits. Meanwhile, contemporary artists like Hanif Pappu express worry over the waning interest among the younger generation, who are often discouraged from pursuing this craft due to its limited financial rewards.

Photo: UNESCO, DBF, Courtesy

Written by Fariha Hossain