13TH ISSUE

The LEGENDS OF CERAMIC INDUSTRY IN BANGLADESH

The ceramic industry in Bangladesh boasts a rich heritage and has produced several legends known for their significant contributions to ceramics and overall company formation. The industry has grown substantially over the past few decades, establishing itself as a leading sector in the country’s economy. In 1992, with the rapidly growing ceramic industry, a nationally recognized trade organization of manufacturers and exporters of ceramic tableware, pottery, tiles, sanitary ware, insulators, and other ceramic products was formed, called the Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers & Exporters Association (BCMEA), under the leadership of many of these ceramic legends. Here, we highlight some legendary leaders and key entrepreneurs who have been instrumental in the journey of the ceramic industry in Bangladesh. These pioneers have laid the foundation for the thriving ceramic industry in Bangladesh, which now covers various subsectors such as tableware, tiles, sanitary ware, and ceramic bricks. Their legacies continue to inspire future generations of ceramic entrepreneurs and professionals. Mohammad Abdul Jabbar Known as the pioneer of the ceramic industry in Bangladesh, Mohammad Abdul Jabbar founded Tajma Ceramic Industries. His contributions laid the foundation for modern ceramic manufacturing in the country. The story of Tajma Ceramic Industries Ltd is quite fascinating. In 1958, the ceramic industry took its nascent steps with only one small tableware manufacturing plant in Bogura. Mohammad Abdul Jabbar, instrumental in promoting and advancing the ceramic factory in Bangladesh, was the Managing Director of the company until his death on May 7, 1985. Tajma Ceramic Industries, recognized as the oldest modern ceramic manufacturing plant in Bangladesh, marked the formal beginning of the ceramic industry in the country. It was the first ceramic earthenware plant to produce porcelain tableware using traditional methods. Tajma played a crucial role in pioneering porcelain tableware production using advanced technology for its time, inspiring many other manufacturers to follow suit. Ariff Wali Mohammed Tabani In 1958, Mirpur Ceramic Works Ltd in Dhaka began producing heavy clay products using German plant and technology, gaining a reputation for manufacturing the best quality ceramic bricks in the subcontinent. The late Ariff Wali Mohammed Tabani, known for his contributions to Mirpur Ceramic Works, played a key role in its evolution. Tabani was the founding Chairman and Managing Director until his death on December 7, 1990. Currently, the company manufactures various types of unglazed tiles and has established two more ceramic companies, Khadim Ceramics and Sunshine Bricks. Both Mirpur Ceramic Works Ltd. and Khadim Ceramics Ltd. have been synonymous with ceramic-based construction materials, manufacturing a comprehensive range of products including blocks, bricks, ornamental screens, claddings, pavers, roofing tiles, and floor and wall tiles, along with the necessary mortars. These materials have been pivotal in landmark projects nationwide, showcasing the group’s commitment to quality and innovation. Md. Abdul Hai Mohammad Abdul Hai was a visionary entrepreneur who founded the country’s first ceramic sanitaryware company, Dacca Ceramics and Sanitary Wares Ltd., in 1969. He embarked on a revolutionary journey in the ceramic sector with the aim of advancing the country through innovative ceramic products. Despite facing political unrest and significant challenges during the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, which led to the destruction of the factory and the loss of materials, Abdul Hai was determined to rebuild the company. After the war, he successfully revived the company in 1974. Dacca Ceramics became the country’s first non-heavy clay building ceramic plant and started the production of sanitaryware in Tongi, Gazipur. Under his leadership, the company grew to become a leader in the country’s ceramics industry, known for its high-quality, durable, and cost-effective products. Abdul Hai’s dedication and resilience played a crucial role in shaping the success of Dacca Ceramics, leaving a lasting legacy in the industry. Mr. Hai passed away on December 21, 1995. Ansar Uddin Ahmed A key figure in Peoples Ceramic Industries, Ansar Uddin Ahmed significantly contributed to the industry through innovation and quality control, helping the company gain a strong foothold in domestic market. In 1966, Peoples Ceramic Industries Ltd, formerly known as Pakistan Ceramic Industries and located in Tongi, Gazipur, began production using modern porcelain tableware manufacturing technology from Japan and started exporting their products. The late Ansar Uddin Ahmed, a respected entrepreneur, inspired many in the field. He was the Managing Director of Peoples Ceramic Industries and Standard Ceramic Industries Ltd and passed away on August 14, 2005. He served as the first President of BCMEA from 1992 to 2002, revolutionizing the export of local ceramic products Rashed Mowdud Khan As the Managing Director of Bengal Fine Ceramics Ltd, Rashed Mowdud Khan advocated for sustainable practices and modern technologies in ceramic production, enhancing the global reputation of Bangladeshi ceramics. In 1986, Bengal Fine Ceramics Ltd, the first stoneware tableware manufacturer in Bangladesh, entered both domestic and international markets. The late Rashed Mowdud Khan was a prominent figure in ceramics, known for his artistic and technical expertise. He served as the first General Secretary of BCMEA from 1992 to 2002 and President four times from 2003 to 2009. He passed away on January 9, 2011. Iftakher Uddin Farhad Mr. Iftakher Uddin Farhad was the Chairman & Managing Director of FARR Ceramics Ltd and served as the President of BCMEA in the 2011-13 session. Established in 2005, FARR Ceramics is a manufacturer and exporter of Euro Fine Porcelain tableware. The company began as an export-oriented business in 2007, producing hard porcelain tableware for both international and local markets. Located in Gazipur, Bangladesh, the plant is equipped with state-of-the-art European ceramics manufacturing technology from Germany and Italy, and decal printing technology from Japan. FARR Ceramics currently exports to 31 countries, from North America to Europe, the Middle East, and India, with a monthly production capacity of 2 million pieces. Mr. Farhad passed away on December 25, 2012. Golam Sabur Tulu The founder of Madhumati Tiles Ltd, Golam Sabur Tulu introduced advanced technologies and designs in ceramic manufacturing, significantly impacting the market in Bangladesh. He was a visionary entrepreneur who made significant contributions to the ceramic industry.

Read More

A Story of Dreams & Determination: South Breeze Housing Ltd.

In the growing heart of Dhaka in the mid-1990s, three brothers stood at the crossroads of ambition and legacy. Aminur Rahman Khan, Anisur Rahman Khan, and M. Ashiqur Rahman Khan were driven by the vision to create something extraordinary—something that would not only honor the legacy of their father, the late M. Abdur Rouf Khan, a pioneering businessman in Bangladesh’s shipping industry, but also transform the way people experienced home. With this dream, South Breeze Housing Ltd. was born in 1995. In their early days, the brothers set their sights on Dhaka’s most coveted neighborhoods—Gulshan, Dhanmondi, and Baridhara. They understood that homes weren’t just structures of concrete and steel but sanctuaries where lives unfolded. They poured their energy into designing residences that offered not just comfort but also an elevated lifestyle. Their first projects quickly gained attention. Each building was a statement of architectural innovation and uncompromising quality. As word spread, South Breeze became synonymous with exclusivity and refinement, setting a new standard for real estate in Bangladesh. “South Breeze is a trailblazer in the real estate industry; they were the first to believe in my vision,” shared Rafiq Azam, the renowned architect of Bangladesh. His firm, Shatotto Architecture for Green Living, has been collaborating with South Breeze Housing Ltd since 1998, being one of the pioneers to facelift the look of the residential real estate. A true artist, Azam seamlessly integrates his creative vision into the buildings he designs, setting his work apart. South Breeze’s ethos was clear: every detail mattered. From meticulously designed single-unit apartments to duplexes with breathtaking views, each project spoke to the company’s relentless pursuit of perfection. Collaborating with the country’s finest architects and engineers, they created masterpieces like ‘South Ripple’ in Gulshan, where residents could wake up to serene lakeside views, and ‘South Terrace’ in Baridhara, a collection of sprawling single-unit homes that felt like a retreat in the middle of the city. This achievement was made possible by Rafiq Azam’s boldness in challenging conventional norms. Reflecting on his inspiration, he shared, “I spent time in Puran Dhaka and noticed how open their houses are—the rooftops are close, the walls are low, and people feel more connected. This inspired me to think, why not use glass walls at the front of my apartments as a breath of fresh air, instead of the usual long concrete walls with barbed wires?” ARCHiTECTURE BEGAN TO CHANGE. PEOPLE STARTED NOTiCiNG THE DiFFERENCE. I BELiEVE WE ARE A COMMUNiTY, AND WALLS ONLY SERVE TO SEPARATE US FROM SOCiETY. THE GROUND FLOOR OF ANY BUiLDiNG iS CRUCiAL—iT SHOULD BE A SHARED SPACE FOR iNTERACTiON, CREATiNG ROOM FOR GREENERY, A PLAYGROUND FOR CHiLDREN, AND A CLEANER, MORE WELCOMiNG WALKWAY Their projects weren’t just buildings—they were homes that told stories, each uniquely tailored to the dreams of their residents. With walls made of glass, lush green porches, and thoughtfully designed playgrounds for children, these spaces fostered a sense of community while blending functionality and artistic vision seamlessly. “My main priority is that the buildings must be green—they need to have grass and plants so that the residents still feel connected to nature. There should also be a waterbody surrounding the building or a pond at its center,” shared Azam. His innovative approach paid off when the company’s out-of-the-ordinary architectural designs caught the world’s attention in 2017. Rafiq Azam won the ‘Cityscape Awards,’ a global accolade for outstanding architecture. This wasn’t just a win for South Breeze but a moment of pride for Bangladesh. Today, South Breeze continues to redefine luxury living. Their portfolio includes stunning developments like ‘South Supreme’ with its rooftop lap pool and panoramic views and ‘South Spring,’ a tranquil haven beside Dhanmondi Lake. Each project reflects the company’s deep understanding of its clients’ needs: privacy, sophistication, and a connection to nature. However, when architect Azam first embarked on his journey, his unconventional approach was met with skepticism. Many doubted the practicality of incorporating nature into buildings, fearing that it would lead to damp walls and significantly higher costs. His innovative requirements, such as large windows for enhanced ventilation, natural light, and expansive views, as well as the use of glass walls and exposed concrete instead of painted surfaces, were considered radical at the time. Despite these concerns, Azam remained steadfast in his vision. “Architecture began to change from that point,” Azam reflected. “People started noticing the difference. I believe we are a community, and walls only serve to separate us from society. For me, the ground floor of any building is crucial—it should be a shared space for interaction, not just a parking lot. That’s why I chose to position the cars at the back, creating room for greenery, a playground for children, and a cleaner, more welcoming walkway.” There was a time when there was no space to add plants in front of the building, so in 2002, I decided to take the garden to the roof—a concept that was considered impossible back then. But I made it happen. I transformed the roof into a thriving garden, which was greatly appreciated by the residents. The innovative decisions taken by South Breeze not only provided them with a significant business advantage but also solidified their reputation as leaders in the industry, thanks to their ability to break barriers and embrace bold ideas,” he added. Rafiq Azam did his job as an architect, but South Breeze took care of his art, making sure they did not lose their value over the years. “I owe it to South Breeze for where I am today and making my architectural dreams come to life,” he concluded. As they continue to expand their portfolio and take on new challenges, one thing is certain: South Breeze isn’t just building homes—they’re shaping the future of living. For those looking for a home that tells a story as unique as theirs, South Breeze offers not just a residence but a legacy. This made South Breeze offer more than a luxury but a lifestyle. Families who move

Read More

Chattogram Hill Tracts Complex: Preserving the values of the people of hills

The complex was designed with one mission in mind: to give visitors the impression that they are experiencing a piece of the Chattogram Hill Tracts right in the heart of bustling Dhaka. The complex serves as a pivot between the people, and architecturally, it has achieved in taking us close to experience Chattogram Hill Tracts without having to travel 300 kilometers. This cultural complex consists of an office building, library, multipurpose hall, amphitheater, restaurant, public plaza, sculptures, and water body in the 2 courtyards, souvenir shops, etc. The public places of this complex are designed in a way to facilitate communal meets, fairs, and cultural events in the public and semi-public zones. Layout, zoning, planning, and construction of the entire complex were modeled after, or at least resembled, structures hailing from the hill tracts, using their common building materials like bamboo, straw, cane, and thatched roofs, which were initially used. A distance of 300 kilometers keeps Dhaka people from experiencing the rich cultures of the Chattogram Hill Tracts (CHT). To bridge that, the Chattogram Hill Tracts Complex has been constructed on Bailey Road, in the heart of the capital city of Bangladesh. This government project has also brought the deeply cultural people of the CHT closer to the Dhakaites. The primary concept behind this 2-acre complex was to serve as a common gathering space where children of hills and city people can come together, as well as exchange intercultural values. To strengthen the complex, modern materials like reinforced concrete and rods were used around it but not to take away its vernacular architectural roots from it. For example, thatched roofs of huts are trussed up with external support struts or buttresses made of very basic material but with superior compressive strength—bamboo. However, the aluminum beams propping up the surrounding top floor serve that symbolic role. The complex was designed with one mission in mind: to give visitors the impression that they are experiencing a piece of the Chattogram Hill Tracts right in the heart of bustling Dhaka. A sloped garden and a fountain mimicking the trickling down of water from a hill face welcome visitors. The sound of water trickling can trick the mind that one is standing next to a natural fountain if they are leaning into the experience. The grand amphitheater is yet another attraction of the Chattogram Hill Tracts Complex. Besides functioning as a venue for plays and shows, this open-air amphitheater can be a wonderful place to sit and enjoy the quiet and spatial experience of this state-of-the-art complex. North of the amphitheater is a crescent-shaped artificial water body. Many beautiful sculptures are displayed between the water body and the amphitheater. These two attractions are joined by a spiraling staircase. The sloped garden on the side of the elevated amphitheater gives a visitor the impression of standing atop a hill. However, visitors will be greeted by beautiful waterscapes at the entrance, even before they reach the best part. The neat waterbody is depressed into the ground, and its step design can remind one of the Rajsthani Chand Baori, although a lot less elaborately. This should give an idea of the extensive care that was spent constructing this complex, which is meant to bolster relations between two peoples. And whether one would like to collect a souvenir, they can do so at the entrance where the souvenir shops are, next to the water body, or they may get their souvenirs at the end of their stay, since the shop would be in the way either way. The number of elements in the complex is high. Yes, there are public spaces that hold all the pretty water bodies and sculptures, semi-public spaces comprising administration buildings, and private spaces that form up a minister’s bungalow, chairman’s bungalow, and dormitories and suites for officials. Yet, the entire complex boasts ample open space through which sufficient air and light flow through without much hindrance. Nooks and crannies of this large project are given room to grow green grass and plants wherever possible. Grass aside, walkways are divided up by lines of pebbles between brick and tile floors, occasionally having concrete stepping slabs. To design freely with nothing held back is one way to go. The designer might as well create something completely fresh and be applauded for it. However, fusion, on the one hand, means staying truthful to each element in the blueprint, and, on the other hand, it also means having to come up with something different by mixing two or more elements. Architects with extensive experience and a clear vision are then responsible for achieving this. Restrictions of conforming to design elements from the hill tracts while embracing modernity were there, but the finished outcome, it seems, has achieved the desired fusion. A fine balance between modern versus nature is evident in this complex. And yet, the interior design of the Chattogram Hill Tracts Complex is a very different picture. Every inch of its interior oozes modernity in every way possible. Hanging staircases supported by high-tensile steel cables, lofty ceilings with wooden panels for ultra-modern design, soft, warm ceiling lights, squeaky clean floor tiles throughout the interior, etc., all add up to the modern style of interior decoration. Since its inception in 2022, the Chattogram Hill Tracts Complex has already hosted two full-fledged Mela (fairs). Culturally, the complex serves as a pivot between the two peoples, and architecturally, it has achieved in taking us close to a CHT experience without having to travel 300 kilometers.

Read More

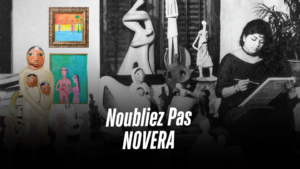

Noubliez Pas Novera

THE WAYS NOVERA PLAYED WITH FORMS AND SHAPES ON HER BEST SCULPTURES HAVE AN INEXPLICABLE AURA THAT CAPTIVATES AND TAKES YOUR SOUL TO A SPACE THAT IS SOMEWHERE BETWEEN THE VAST ABSTRACT AND YET TANGIBLE. In August of 1960, on the ground floor of the Central Public Library building of the University of Dhaka, showcasing 75 of her artworks sculpted between 1956 and 1960, Novera Ahmed had her first solo exhibition titled “Inner Gaze.” This formidable exhibition arguably sparked the genesis of modern sculpting practice in both West and East Pakistan (now present-day Bangladesh). She was the first-ever sculptor from the undivided Pakistani region. Novera Ahmed was born on March 29, 1939, in Kolkata, British India, and on the occasion of her 85th birthday, this attempt is to reminisce about one of the finest artistic personages from this part of the world. Today, Novera’s importance is cemented in the history of art in this region, and it seems that she has a newly found celebrity status, especially amongst the younger generation of art enthusiasts, but for decades and even today, to a significant extent, Novera’s public repute mostly synonymizes as enigmatic. But Novera should not be important because of her public portrayal that branched from her peers: that she was a good-looking female artist of prodigal calibre who worked and lived independently as a divorcee in a patriarchal society; the way she did her buns and draped herself in black sari and curated her look as Baishnabi wearing Rudraksha garland and tilak on her forehead; that she used to exploit her male peers; that she had a sentiment because of the way she was gazed upon and which is why she eventually left Bangladesh; the list of such narratives that circulated her is pretty long. Novera is important because of her artworks; the quality of her artworks effortlessly transcends the tags she was associated with, which boxed her only as an eccentric rebellious character, undervaluing her art. The ways Novera played with forms and shapes on her best sculptures have an inexplicable aura that captivates and takes your soul to a space that is somewhere between the vast abstract and yet tangible. Novera used to travel around and gradually minimised her activity in the local art scene. Her complete disappearance from the scene in 1970 after she permanently moved to France eventually turned her into a myth. Later, she married the love of her life Gregoire de Brouhns in 1984. Although there is no concrete evidence regarding why she left, it is speculated that the key reasons are monetary and no recognition even from her peers. Belonging to a middle-class background, she almost single-handedly established a medium that was still very new in the region so there were not many commissions for her so she could continue her practice and earn a decent living. There was also an uncanny silence from her peers, which only fueled the collective negligence towards her. Even in the artist community, she was only remembered as an amateur female sculptor. In fact, for a while, it was even established that she was dead, and it was only in late 1998 after a brochure of her 1960 exhibition was found, that it catalysed the rebirth of discussions about artist Novera Ahmed. Although Novera studied in Europe and like many other artists, had that influence on her works in her earliest years, very soon she found her style. If we examine Novera’s available discography of sculptures and paintings, it resembles the wide array of subject matters she had her interests. Notably, in artworks from her formative years, it is very evident how much she was fascistically influenced by her roots. The way she took Bengali folk elements and ethereally blended them within her modernist approach of practice shows how revolutionary she was. Novera’s idea of using cement instead of large blocks of stone or wood, as they are scarce in this region, and sculpting such smooth cement sculptures, which is very difficult to accomplish, shows both her innovativeness and technical prowess. When she started traveling to Southeast Asia, she decided to collect scrap metal from the debris of the U.S. Air Force plane used in the Vietnam War and use it as materials for her newer sculptures at the time. For a long period, little to no care was taken to preserve most of Noveraís works that are in Bangladesh. In fact, for a while, it was even established that she was dead, and it was only in late 1998 after a brochure of her 1960 exhibition was found, that catalysed the rebirth of discussions about artist Novera Ahmed. She was also highly influenced by Indigenous and Buddhist themes; in fact, she once said that the form of the concrete structures of the Shaheed Minar (which she co-designed with another notable artist, Hamidur Rahman—a topic that still has loads of debate regarding who came up with the original idea) is inspired by the idea of an ascending hand of Buddha. The long list of her oeuvres includes works like Cow With Two Figures (1958), Serpent Nommé Désire (1972), Le Djinn (1973), Le Heron (1982), Le Baron Fou (2001), etc. In her France years, even after Novera was wheelchair-bound after a life-altering car accident, she continued working with her forever devotion and love towards art, till she was bedridden due to health complications when she was older and eventually passed away on May 6, 2015. For a long period, little to no care was taken to preserve most of Novera’s works that are in Bangladesh. The whereabouts of many of her works are yet unknown, and the ones that survived did so due to her patrons and private collectors. A collection of her works and memorabilia is at the Musee Novera Ahmed at La Roche-Guyon in northern France which was set up by her dear husband. Currently, only 33 of Novera’s sculptures are in the collection of the Bangladesh National Museum, and the gorgeous frieze that she

Read More

Reviving Our Roots A Journey of Abu Sayeed M. Ahmed From Legacy To Leadership

While many architects push the boundaries of innovation, there have been some who charted a different course. Instead of focusing solely on creating the new, Architect Dr. Abu Sayeed M. Ahmed turned his gaze to the past—reviving forgotten monuments and ancient buildings. A pioneer in conservation architecture, he has dedicated his life to protecting and restoring the architectural jewels of Bangladesh. For Dr. Sayeed, preserving heritage is not just about safeguarding structures; it’s about understanding who we are and how the past shapes our identity today. From restoring historic mosques and colonial buildings to leading the Institute of Architects Bangladesh as president thrice in a row and serving as the elected president of ARCASIA on an international level, his contributions have earned him both national and global recognition. As an educator and author, his efforts in heritage protection continue to inspire future generations of architects. Dr. Sayeed’s legacy as a guardian of Bangladesh’s architectural treasures makes him an enduring force in both the past and future of the nation’s architectural identity. A pioneer in conservation architecture, he has dedicated his life to protecting and restoring the architectural jewels of Bangladesh. For Dr. Sayeed, preserving heritage is not just about safeguarding structures; it’s about understanding who we are and how the past shapes our identity today. From the Water’s Edge: A Childhood in Comilla Long before the architectural world knew his name, there was a young boy in Comilla, Bangladesh, who spent his days by the waterside, watching the reflections of ancient trees shimmer in the lights and ponds. In this quaint town, the city’s water bodies—like Dharmasagar and Rani’s Dighi—were more than mere landmarks; they were playgrounds, gathering spots, and the backdrop to countless moments of childhood joy. Football games often ended with a refreshing dip in the cool waters, and laughter echoed across the banks, blending with the gentle sounds of nature. That little boy, Abu Sayeed M. Ahmed, found joy in simple things like drawing intricate sketches, building models, and creating Eid cards. His love for the technical precision of his creations grew in the quiet corners of his home and school, unknowingly laying the foundation of his future as an architect. Abu Sayeed’s fascination with design was nurtured by his father, Abdur Rashid, a principled educator, and his mother, Helena Begum, whose warmth and love kept the heart of their home alive. The roots of his curiosity about history and architecture grew deep in the soil of Comilla, where he first learned to see beauty in the details around him. Even as a student at Comilla Zilla School and later Comilla Victoria College, Sayeed stood out. His involvement in Scouting allowed him to explore Bangladesh’s landscapes, meet people from different walks of life, and develop a strong sense of leadership. By the time he graduated in 1976, these experiences had shaped his collaborative spirit and a love for discovery—qualities that would define his career for years to come. His bond with his architecture batchmates was legendary. Known as the “batch of talents,” they shared a camaraderie that extended beyond classrooms. From organizing grand tours across India and Bangladesh to planning picnics, Sayeed often emerged as the natural leader. His ability to bring people together flourished during these years, and the friendships he built remain strong to this day. In 1983, he graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture, ready to leave his mark on the world. Stepping Into a New World: The BUET Years In 1976, Abu Sayeed entered BUET’s Department of Architecture, a choice that marked the beginning of a transformative chapter. Life at BUET was unlike anything he had known. Sharing dormitories with students from other disciplines introduced him to diverse perspectives. While his engineering peers were deep in equations, Sayeed and his classmates were sketching, brainstorming, and working late into the night on design projects. The Architect Emerges: Early Projects at ECBL Sayeed’s first professional step was joining the consultancy firm ECBL, where he worked for four years. It was a period of intense learning and growth. He became involved in landmark projects such as the Bangabandhu Hall of Dhaka University, Nagar Bhaban, the Air Force Academy in Jessore, and the Dhaka Cantonment’s central mosque and library. These projects gave him firsthand experience in balancing design with functionality. His natural f lair for leadership and meticulous approach to detail made him an asset to the firm. However, Sayeed knew his journey was far from over—he dreamed of exploring new horizons. A New Chapter in Germany: Rediscovering Bangladesh In pursuit of higher education, Abu Sayeed M. Ahmed embarked on a bold journey to Germany to pursue his master’s degree in architecture. Before leaving, he received two meaningful gifts—one from Lailun Nahar Ikram, the Managing Director of ECBL, who gifted him $1,000, and another from Prof. Abu Haider Imam Uddin, a colleague at ECBL, who presented him with the book Islamic Heritage of Bangladesh by Dr. Enamul Haque. Little did he know, this book would become a faithful companion in his new chapter abroad. The transition was anything but easy. Sayeed had to learn German from scratch, adapt to a foreign culture, and navigate a competitive academic environment. He lived in a hostel with students from all over the world, and conversations inevitably turned to his homeland. “What makes your country special?” his peers would ask. At first, Sayeed found himself at a loss for words, unsure of how to convey the richness of Bangladesh’s heritage. But then, the book he had been gifted came to his mind. The book Islamic Heritage of Bangladesh became his bridge to the world. He started to share Bangladesh’s architectural treasures—the Sixty Dome Mosque, the Small Sona Mosque, then the Paharpur Monastery, Mahasthangarh, and so on. His peers were astounded. “Bangladesh has a heritage this rich?” they asked, their eyes wide with surprise. They had never imagined that such ancient, awe-inspiring architecture existed in a country they often perceived as impoverished. These moments sparked something

Read More

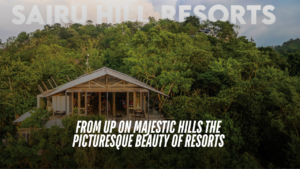

FROM UP ON MAJESTIC HILLS FROM UP ON MAJESTIC HILLS THE PICTURESQUE BEAUTY OF RESORTS

Discovering A Gem Like Sairu, Amidst The Serena Hills Of Bandarban, Will Feel Like Uncovering A Hidden Treasure. The Experience Will Be Nothing Short Of Magical, Blending Natural Beauty With A Sense Of Tranquility That Only The Mountains Can Provide. Sairu is a contemporary eco-resort that blends modern luxury with natural harmony. Designed with sustainability in mind, it incorporates local materials like stone and bamboo to create a rustic yet refined aesthetic that seamlessly integrates with the surrounding environment. If given a choice between the beach and the mountains, I wouldn’t hesitate to pick the mountains. Exploring mountainous terrain has always been a source of joy for me, and discovering a gem like Sairu, amidst the serene hills of Bandarban, felt like uncovering a hidden treasure. The experience was nothing short of magical, blending natural beauty with a sense of tranquillity that only the mountains can provide. The resort is around a 40-minute drive from Bandarban town. Upon entering the compound of Sairu, the f irst thing that will grab your attention is how everything looks in place and blends effortlessly with the surrounding topography. There is not a single element or structure you will find there that is off-putting. To the entrance left of lies the the reception and dining area, nestled beside a tranquil water body. From the hanging balcony of the eating zone, the panoramic view of the towering hills and the Shanghu River is breathtaking, offering a visual feast that captures the essence of Bandarban’s serene charm. To the right of the entrance, cottages are arranged in terraced layers along the hillside, accessible only via steps. For those less accustomed to physical activity, the steep climb might feel challenging, especially with frequent trips. However, the effort is well rewarded with changing, picturesque views at every turn. Mini golf carts are available for transporting luggage and assisting individuals with disabilities. At the hill’s summit lies the infinity pool and jacuzzi, offering unparalleled vistas. Rest stops throughout the resort invite you to pause and enjoy the stunning beauty of Bandarban. Long ago in Bandarban, a Mro princess named Sairu fell in love with a prince from a rival hill tribe, defying tribal rules. Their secret meetings ended tragically when the prince was forced into an arranged marriage. Heartbroken, Sairu disappeared into the hills. The resort is named after this story, with “Sairu Point” marked by entwined trees on a hill, symbolizing their love. The Sairu Hill Resort draws its name and logo from this legend, preserving its memory for visitors to honor. Sairu is a contemporary eco-resort that blends modern luxury with natural harmony. Designed with sustainability in mind, it incorporates local materials like stone and bamboo to create a rustic yet refined aesthetic that seam lessly integrates with the surrounding environment. The cottages at Sairu are thoughtfully priced, offering options tailored to your preferred view. Each cottage features a private balcony and a spacious washroom with a unique, nature-facing concrete bathtub—a rare luxury in the country. The rooms are generously sized and adorned with colorful jute rugs, bamboo curtains, and furniture crafted from tree logs. A standout piece is the giant coffee table, made from a single slice of a tree trunk. Modern amenities such as toiletries, skincare essentials, laundry services, and safes ensure a comfortable stay. The culinary excellence of the resort is also a notable mention if you are into local cuisine. Their downhill restaurant provides all kinds of meals and offers both à la carte menus with diverse cuisines and buffet options. Open to all visitors, not just guests, it welcoming provides space a for anyone looking to enjoy a meal amid the serene surroundings. There is also a badminton court in another part of the downhill. The resort’s design and execution were spearheaded by DOMUS, a renowned architectural consultancy in Bangladesh, with Principal Architect Mustafa Ameen envisioning a “less is more” approach. The master plan was crafted to respect the natural terrain, with structures elevated on steel stilts to preserve the contours and existing trees left untouched. Additional greenery enhanced the landscape, ensuring harmony with the surroundings. Maximizing panoramic views, the design integrates modern luxury with environmental sensitivity, with the only major alteration being the driveway carved into the hill. Water was sourced from a spring 1,200 feet below, showcasing remarkable ingenuity. The mornings at Sairu are invigorating, with a gentle breeze whispering through the trees, while nighttime transforms into a magical spectacle, as the starlit sky casts an enchanting spell, leaving visitors in awe. Once you are inside Sairu, you will not feel the need to go elsewhere, as the tasteful setup with modern amenities will you amazed. But, yet, if you have plans to keep explore the surroundings, Sairu will arrange that for you. You can rent a jeep or CNG from them and explore the nearby tourist attractions like Nilgiri Mountain. Written By Kaniz Supriya

Read More

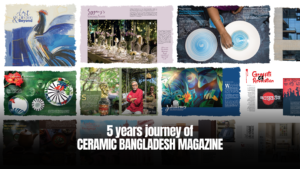

5 years journey of CERAMIC BANGLADESH MAGAZINE

walking through the memory lane, the 5-year journey of Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine seems like a dream of yesterday. During the planning of the Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2019, the magazine began its journey by providing complimentary copies to exhibitors to educate them about the ceramic industry in Bangladesh. Along with the success of the Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2019, everyone particularly praised the magazine, which encouraged us to come up with the next issue in 2021. Chief Editor Mr. Irfan Uddin was recollecting the memories in this way while sharing his experience of working closely with the magazine. Initially, the magazine focused on Bangladesh’s ceramic industry, its overall future, prospects, growth, etc., to bring limelight to the overall sector. Due to Covid-19, it was impossible to continue the publication in 2020. But after that, Ceramic Bangladesh was publishing full-fledged from 2021 at the end of the year. Since then, the magazine has completed its 13th issue and plans to publish bimonthly from 2025. The journey was a rollercoaster for all the team members, along with the editor, sub-editor, coordinator, designer, photographer, and writers. Everyone took a leap of faith to explore a new publication arena with their enthusiasm, interest, and love for taking challenges. The editor of the magazine, Salahuddin A. Talukder, expressed his immense affection for Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine. It was a challenge to sustain the magazine and keep up the top-notch quality so that it would be liked and praised by all. The projects we have focused on were unique and interesting, and each one has a new way of unfolding the journey of development and growth in Bangladesh. While interviewing the subeditor, Rehnuma Tasnim Sheefa, it was really interesting to know how they came up with the names of the segments and selected projects to feature initially. Reminiscing on the initial projects and works, she mentioned that at the beginning, most of the write-ups were done by the editor, Salahuddin Ahmaad Talukder, and himself, along with 2 to 3 writers. Photographer Junaid Hasan Pranto and designer Ali Haider created magic with their photography and layout to make those features alive by narrating a story visually for the readers. The 1st issue of the magazine was prepared by Ant Network, which encouraged BCMEA board members to approve the work of the publication and enable BCMEA to work on the magazine internally. With the publication of the 2nd issue, considering the contribution of the architects and their close involvement with the ceramic industry in their projects, the magazine started to focus on architects and their significant works, various mega projects, interior and exterior insights, industry-related content, and some exclusive and unique projects related to the use of tableware, tiles, ceramic bricks, sanitaryware, etc. Through the magazine, readers learned that Bangladesh is the only country where the maximum number of national establishments are made with red ceramic bricks, a matter of pride for the ceramic industry. There were also some interesting coverages of the projects from a wide range of collections under different segments. For example, for the segment Architectural Regime, Alenbari Mosque of PWD was featured, which is a geometric-shaped prayer space with a dramatic skylight that represents the combination of art and architecture in every part of the project. The feature on Monno Ceramic for Ceramic Central reminds the reader about the legacy of ceramic tableware in Bangladesh, which has created a corner in every showcase of each household and the heart of Bengali mothers. Under Suasive senses, unique ideas like Ajo Idea Space use their own crockery sets to serve their food sustainably and reduce the wastage of food. Some of the exclusive features of the brilliant minds of the country were presented through the magazine. Architect Rafiq Azam recalled his childhood memories and newfound inspiration for sustainable architecture practices from his surroundings, exploring new arenas of work that are inspirations to many young architects. The creator of the new city skyline Architect Mustapha Khalid Palash unfolds the dream of making the city more sustainable and living worthy for the city dwellers. The Mason Master Architect Mohammad Foyez Ullah’s projects represent the combination of modern architecture by designing sleek concrete buildings and making them stand out to praise the beauty of the creation. Apart from them, Architect Mamnoon Murshed Chowdhury, Architect Mahmudul Anwar Riyaad, Architect Tanya Karim, Architect Nurur Rahman Khan, Architect Masudur Rahman Khan, and Architect Salauddin Ahmed’s contributions and journeys of their personal and professional lives are worthy to explore through the magazine. They have shared their life journey, learning, and their experiences under the architectural regime segment. It was a documentation of the living legends and the inspiration behind their creations through the magazine for future generations, added by Sheefa. In the segment Interior Insight, we featured different well-designed restaurants and offices. Some features were also on entrepreneurial stories to encourage new people to start their journeys in similar industries. Exclusive mega projects like MetroRail, Padma Bridge, Kamlapur Railway Station, etc. were also highlighted in the cover stories of our magazine. In the Heritage segment, sites like Lalbagh Kella, Tara Mosque, Shat Gambuj Mosque, Terracotta Temple, etc. were also covered. In parallel, we also focused on scenic sights, covering touristy destinations. From financial institutes to real estate, we have tried our best to cover the wide band. Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine has grown with some excellent team members. Without their dedication and utmost effort, it would not be possible to come such a long way. The former core team members of BCMEA, Mahfuza Tasnim Noshin, Kazi Sumaiya Ahmed, and Anamika Rahman, shared their journey with the magazine as they have closely worked with the CBM since its initiation. They shared their utmost affection and recalled their journey while working on such an interesting project from scratch. To sum up the journey of Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine, the dedication, effort, and consistency of all the team members is remarkable. Without their continuous

Read More