The Ceramic Expo bustling with a large number of people on the 2nd day

Dhaka (28 November 2025): The BCMEA Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025 has gathered in the capital. On the second day of this four-day vibrant event, the International Convention City Bashundhara was bustling with local and foreign visitors, exhibitors, businessmen, engineers, architects, and representatives from various companies. The arriving businessmen held meetings with B2B, B2C, and representatives from different companies. In the various pavilions and stalls, they demonstrated their products and ensured spot orders. Senior officials of various companies stated that due to the holiday, there was a noticeable crowd of visitors from the morning, and many placed orders for products. Artist Shahin Mahmud Reza, participating in the fair for the first time, expressed satisfaction with the organization of the fair. As every year, dealer Md. Rahim Uddin has come to the expo from Chittagong. He mentioned that he has seen many new designs at this year’s expo. Following this, a seminar was held in a very large hall where relevant stakeholders participated. Mohammad Khaled Hasan, Deputy General Manager of Sheltech Ceramics Limited, the titled sponsor of the expo, mentioned that the ceramic industry of Bangladesh is a glorious sector. Earlier, we used to import ceramic products at about 80 percent, but nowadays approximately 15 to 20 percent we import; we export it and gradually extend its market. One of the visiting engineers stated that this sector has achieved an average growth of over 20 percent, setting records. Despite the gas crisis, the uninterrupted supply of electricity, and various domestic and international crises, this industry remains an emerging sector. Unlike the ready-made garment, jute, and textile sectors, which receive policy support, this sector has reached a respectable position solely due to the courageous initiatives of entrepreneurs. One could say that the ceramic industry has brought about a silent revolution in the last 10 years. Through rapid expansion in the local market, stable presence in foreign markets, and massive job creation, this industry has demonstrated that with industry-friendly policies, uninterrupted gas supply, and proper branding, it will be capable of exporting billions of dollars in the future solely in Asia. Today, there are about 65–70 ceramic factories and brands in the country producing various products including tableware, tiles, sanitary ware, and electric insulators. As a result, instead of being import-dependent like before, Bangladesh now fulfils a large part of its own demand and sends excess production to the global market; this is not a small change but rather a picture of slow yet steady success in industrial policy. The domestic market for Bangladeshi ceramic products is currently considered to be worth around 70 to 90 billion BDT, with annual growth hovering around 20 percent for a long time. Once where 80 percent of the market was occupied by foreign brands, today local companies meet nearly 85 percent of market demand; in tableware, local participation exceeds 90 percent. Some visitors stated rapid urbanisation, development in the housing sector, rising incomes of the middle class, and changes in lifestyle perspectives have contributed to this achievement. The use of tiles and sanitary products in new flats, shopping malls, hotels, and restaurants is now not just a necessity but also a symbol of prestige and taste. In this way, the ceramic industry has become directly linked to the dreams of the urban middle class, as if the contribution of this industry is silently signing on the walls and floors of every new flat. Although the export earnings of the ceramic industry are still seen by many as ‘less compared to the size of investment’, in reality, it has passed an important initial phase. In the fiscal year 2022–23, the export earnings from ceramic products reached around 43–55 million USD (equivalent to 600–650 crore BDT), which is the highest in four years. The export growth in this sector from 2021–22 to 2022–23 was over 21 percent, although in the fiscal year 2023–24, it has slightly decreased by nearly two percent. Tableware occupies the largest share in the export basket; recently, tiles have also been added. Bangladeshi ceramic products now go to over 50 countries; United States, Canada, Germany, France, Italy, Japan, and various countries in the Middle East are major destinations. In such a reality, despite slight fluctuations, it is clear that Bangladesh is establishing itself as a reliable source of ‘low-cost but quality’ ceramic products in the global market. This expo carries a very high potential for the Bangladeshi ceramic industry and also plays a vital role in the economy. Written by: Mizanur Rahman Jewel

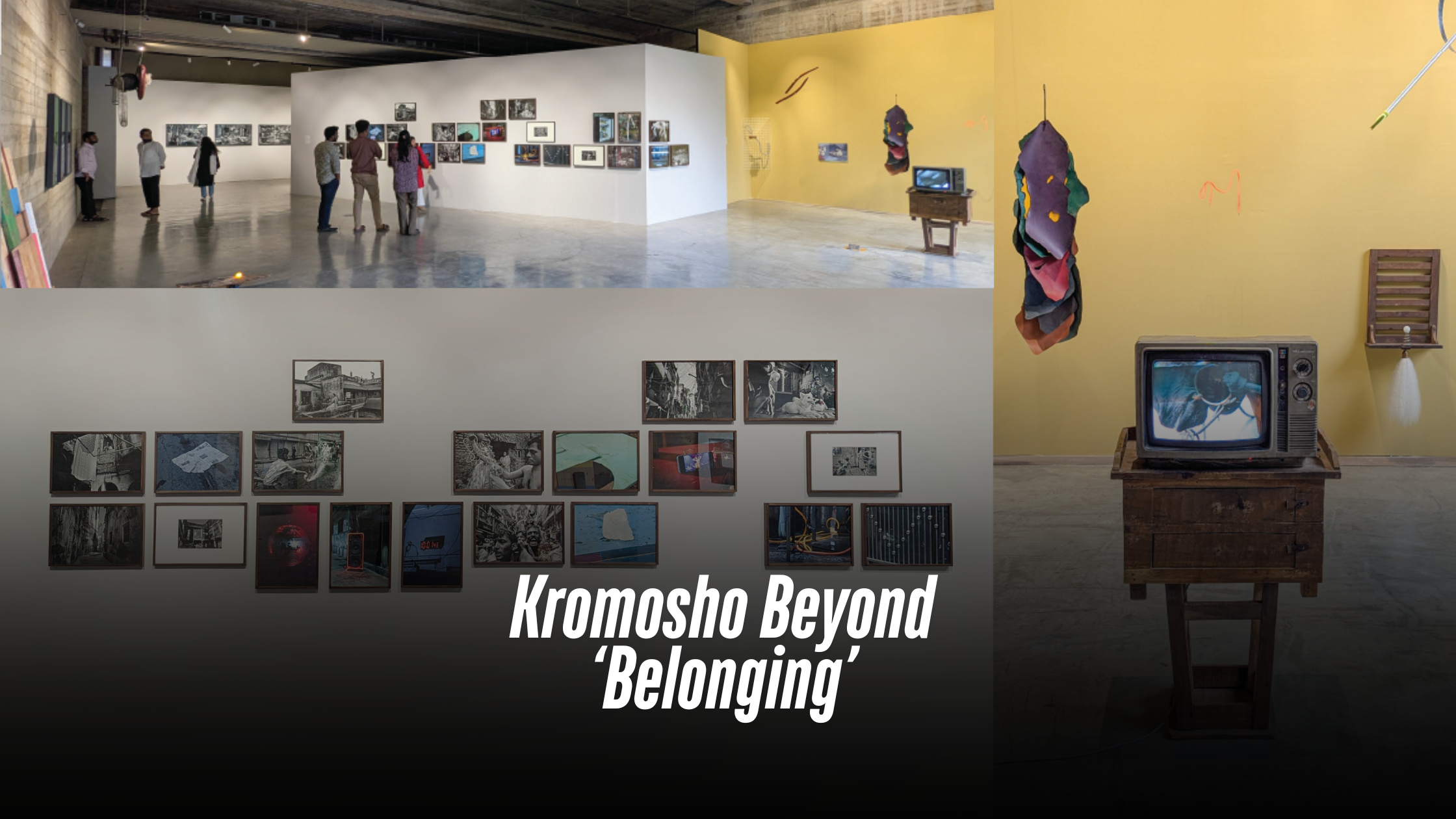

Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025 Opens in Dhaka, Showcasing National Industry to Global Markets

A four-day international exhibition has commenced in Dhaka to present Bangladesh’s ceramic industry to local, global buyers and investors. Organized by the Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BCMEA), Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025, one of Asia’s largest and most influential international ceramic trade exhibitions, is being held at the International Convention City Bashundhara (ICCB). This fourth edition of the expo is set to host 135 companies and 300 global brands from 25 countries, including host Bangladesh, while more than 500 international delegates and buyers are scheduled to participate, underscoring the increasing global focus on Bangladesh’s rapidly expanding ceramic sector. BCMEA confirmed that the exhibition will feature three technical seminars, a job fair, extensive B2B and B2C meetings, live product demonstrations, spot-order opportunities, raffle draws, attractive giveaways, and the launch of new ceramic technologies and products. The exhibition is open to visitors free of charge from 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM daily and is expected to attract buyers, suppliers, and stakeholders from across the sector. Speaking at the opening ceremony, Commerce Adviser Sheikh Bashir Uddin said the industry, once fully dependent on imports, has now secured a strong position in global markets. He stressed the need for advanced technology adoption and uninterrupted energy supply to maintain production efficiency. The adviser added that the Interim Government will provide all necessary policy and regulatory support to accelerate the industry’s expansion. Following the inauguration, the adviser and distinguished guests visited various pavilions and stalls, where they praised the innovations and product displays. The commerce adviser expressed confidence that the sector will become increasingly export-driven. The event was presided over by BCMEA President Moinul Islam. Other speakers included Export Promotion Bureau Vice-Chairman Mohammad Hasan Arif, Italian Ambassador to Bangladesh Antonio Alessandro, BCMEA Senior Vice-Presidents Md Mamunur Rashid and Abdul Hakim Sumon, and BCMEA General Secretary Irfan Uddin. BCMEA President Moinul Islam noted that the ceramic industry has experienced rapid growth over the past decade. More than 70 factories producing tableware, tiles, and sanitary ware are currently in operation, serving a domestic market valued at Tk 8,000 crore annually. Over the last ten years, both production and investment have increased by nearly 150 percent. He added that Bangladesh now exports ceramic products to more than 50 countries, earning nearly Tk 500 crore in annual export revenue. Total industry investment exceeds Tk 18,000 crore, with the sector providing direct and indirect employment to approximately 500,000 workers. He further highlighted that major ceramic-producing nations, including China and India, are increasingly exploring investment opportunities in Bangladesh due to its competitive cost advantages and expanding global footprint. Fair Committee Chairman and BCMEA Secretary-General Irfan Uddin said Bangladeshi ceramic products are gaining international recognition for their quality, durability, and modern design. Demand is rising, and new global markets are opening for local manufacturers. He added that the expo will spotlight next-generation ceramic technologies, including automation, advanced digital printing, robotic handling, and upgraded production lines. “Smart tiles and sensor-integrated ceramic products, which are already popular worldwide, are expected to enter the domestic market soon. This expo will help local manufacturers connect with these emerging technologies,” he said. The event is supported by key industry partners. Sheltech Ceramics is serving as the Principal Sponsor, while DBL Ceramics, Akij Ceramics, and Meghna Ceramics are Platinum Sponsors. Gold Sponsors include Mir Ceramics, Abul Khayer Ceramics, HLT DLT, and SACMI, reflecting broad industry backing for the international expo. Written by: Mizanur Rahman Jewel

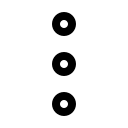

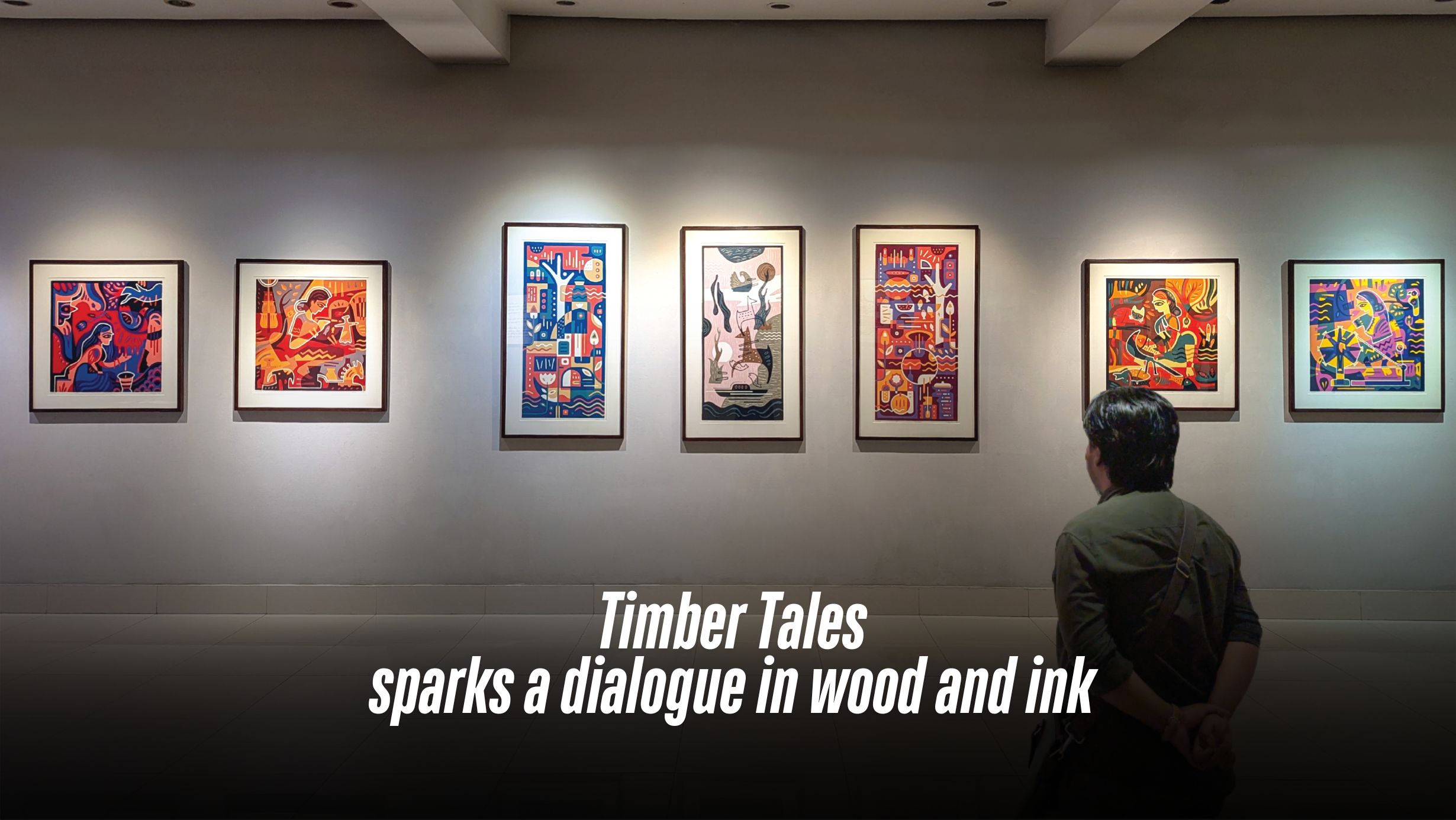

Timber Tales sparks a dialogue in wood and ink

The ongoing exhibition titled Timber Tales at La Galerie, Alliance Française de Dhaka invites audiences to experience the collaborative journey of three emerging artists who explore memory, process, and material through the art of woodcut printmaking. Within the exhibition, a faint, earthy scent of wood and ink hangs in the air. Walking into the gallery, some might find themselves pausing longer than expected, tracing the grain of the wood as if searching for their own stories between the lines. The exhibition features three artists—Rakib Alam Shanto, Shakil Mridha, and Abu Al Naeem—who express individuality through their woodcut prints. This contemplative exhibition is running from June 17 to June 25, 2025. Curated by the artists themselves, the exhibition reimagines the possibilities of woodcuts as a medium. Here, the tactile intimacy of carved timber meets the visual language of reflection, nostalgia, and search. As you wander through the space, individual voices emerge. Shakil Mridha’s work, with its minimalistic yet profound geometric forms, feels like a contemporary ode to Bangladeshi folk art, skillfully abstracting familiar motifs. Rakib Alam Shanto’s large-scale black-and-white pieces command attention, a powerful revival of a tradition, showcasing his remarkable focus. Abu Al Naeem’s pieces, often abstract, subtly reveal hidden figures, reflecting his continuous exploration of materials and techniques. Each artist, in their unique way, elevates woodcut beyond mere reproduction, transforming it into a medium of profound personal expression. And through that expression, each of their work reflects the heart of the creative process, where stories are carved into existence. At the heart of Timber Tales is a tribute to beginnings, to the mentor who shaped them, and to the space where it all began. Their acknowledgement of Professor Md. Anisuzzaman, whose generous guidance helped steer their vision, reveals the deeply collaborative ethos of the show. “This is where it all began—for the three of us,” reads a line from the exhibition note, underscoring the intimate bond between craft, community, and coming-of-age. In an era of digital immediacy, there’s something revolutionary about the deliberate slowness of woodcuts. And the three artists have breathed new life into the ancient art of woodcut. More than just a technique, it’s a dialogue between human touch and natural materials. Each frame holds a deeper narrative of tireless dedication—the careful selection of wood, the precise cuts, the methodical inking, and the final, expectant press. Open to all and continuing until 25 June 2025, Timber Tales will leave visitors with more than just images on paper. In a city rushing to reinvent itself, the exhibition feels like a pause, a reminder of our roots with a sense of belonging—to the artists, to the materials, and to the timeless, meditative act of making. Written by Samira Ahsan