Bangladeshi Hotels, Resorts Win Big at South Asian Travel Awards 2025

Bangladesh’s hospitality sector received a resounding endorsement on the international stage as several leading local hotels, resorts, and tour operators were honoured at the South Asian Travel Awards (SATA) 2025, held at the Cinnamon Grand in Colombo. The glittering ceremony, widely regarded as one of the region’s most prestigious events in the travel and tourism calendar, brought together top-tier organisations from Sri Lanka, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh. A total of 53 Gold Awards and 113 Silver Awards were presented across a range of categories, recognising excellence in service, innovation, and guest experience. Bangladeshi winners spanned multiple categories, reflecting the country’s growing reputation as a destination of choice for regional and international travellers. Award Winners from Bangladesh Baywatch: South Asia’s Best New Hotel and South Asia’s Leading Beach Resort HANSA – A Premium Residence: Leading Designer Hotel/Resort Holiday Inn Dhaka City Centre: Leading City Hotel Intercontinental Dhaka: Leading Luxury Hotel Momo Inn: Leading Family Hotel & Resort and Leading Convention Center Award Platinum Grand: Leading Boutique Hotel Platinum Residence: Leading City Hotel and Leading Budget Hotel Radisson Blu Chattogram Bay View: Best Eco-Friendly Hotel Radisson Blu Dhaka: Leading Airport Hotel and Leading Meeting & Events Sayeman Beach Resort: Leading Wedding Hotel/Resort Sayeman Heritage: Leading Heritage Hotel/Resort The Palace Luxury Resort: Leading Palace Hotel The Peninsula Chittagong: Best CSR Program, Leading F&B Hotel, and Leading Business Hotel The Westin Dhaka: Leading Wellness and Spa Hotel/Resort Bangladesh Tour Group (BTG): South Asia’s Leading Inbound Travel Agent and Best Promotion Campaign in South Asia Travel Classic (Pvt.) Limited: Leading Travel Agent – Outbound Winning awards in different categories was no easy feat. Each submission underwent a rigorous selection and evaluation process. The SATA 2025 Awards were presented to organisations that embody excellence in service delivery, innovation, sustainability, leadership, and overall industry impact. During the evaluation stage, 60 percent of the marks came from the professional judges’ report cards, with the remaining 40 percent from online public voting. Judges scored submissions based on multiple criteria: service excellence, innovation and improvement, customer satisfaction, sustainability and responsibility, operational excellence and safety, sales and revenue performance, leadership and team development, and industry contribution. This year, SATA placed particular emphasis on sustainability, cultural authenticity, and digital innovation. “SATA brings together over 300 delegates from across the South Asian region to celebrate the best of South Asian hospitality brands,” said SATA President Ismail Hameed at a press conference held during the event. He added that international establishments such as the Taj Mahal Palace, as well as brands from Nepal and Bhutan, which are unique in their own right, took part in this year’s show. “From travel agents’ associations to hotel associations to tourism boards — all are part of SATA,” Hameed said. He noted that South Asian destinations hold great tourism potential, offering everything from cool weather and beaches to mountains, heritage, history, culture, food, and delicacies. Md Mohsin Hoq Himel, Secretary of the Bangladesh International Hotel Association (BIHA), who attended the event, said: “BIHA has been working with the South Asian Travel Awards in Bangladesh.” Under the overall guidance of Hakim Ali, founder of BIHA, the association has participated in the prestigious event every year, he said. Through this platform, BIHA aims to highlight the service standards of Bangladesh’s local hotels and resorts, showcasing their uniqueness and distinctiveness alongside other regional hotels, Himel added. “This year, every Bangladeshi hotel and resort has achieved remarkable positions. We extend our heartfelt congratulations to all the award winners.” According to representatives of Bangladesh’s hospitality sector, this international recognition will further advance the country’s tourism and hotel industry in the global market and strengthen Bangladesh’s brand image worldwide, he said. The first edition of the South Asian Travel Awards began in 2016 and has been organised by Highrise every year since, with the support of multiple associations and tourism bodies from across the South Asian region, according to the SATA website. The annual search for South Asia’s most outstanding travel organisations spans a month each year from March to April, calling upon industry professionals to name their preferred travel suppliers in the region who have risen above the competition and surpassed expectations, it read. “The awards programme continues to serve as a platform for nations to come together, not in competition, but in celebration of shared triumphs and brilliance.” Written by Nibir Ayaan

Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025: From Local Clay to Global Stage

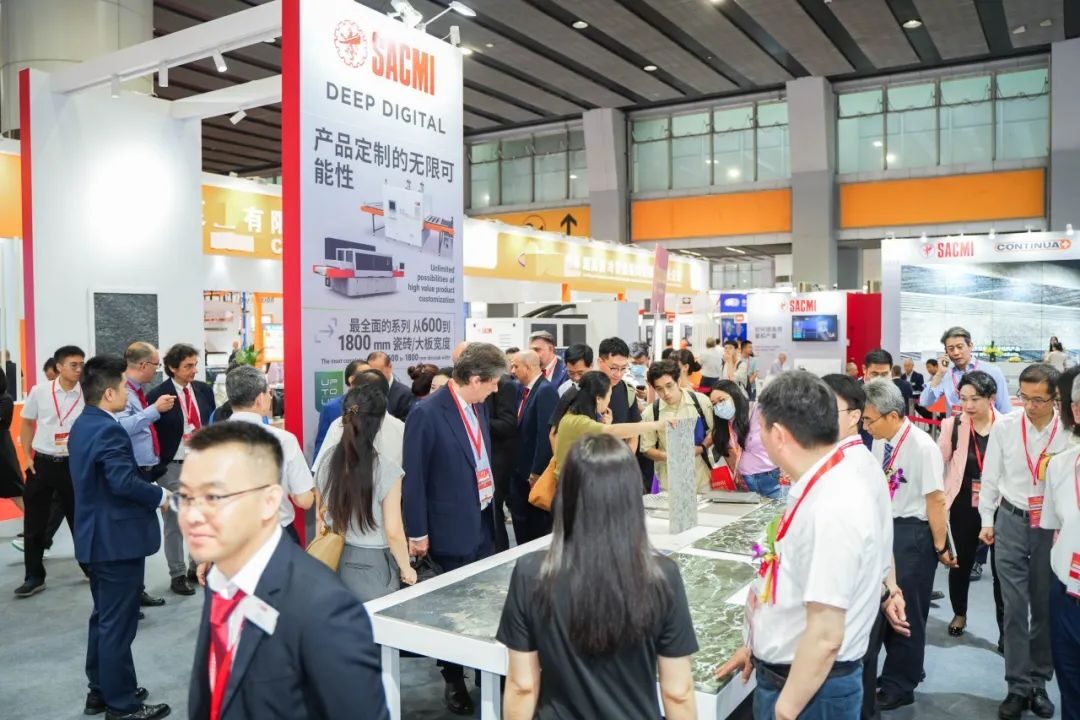

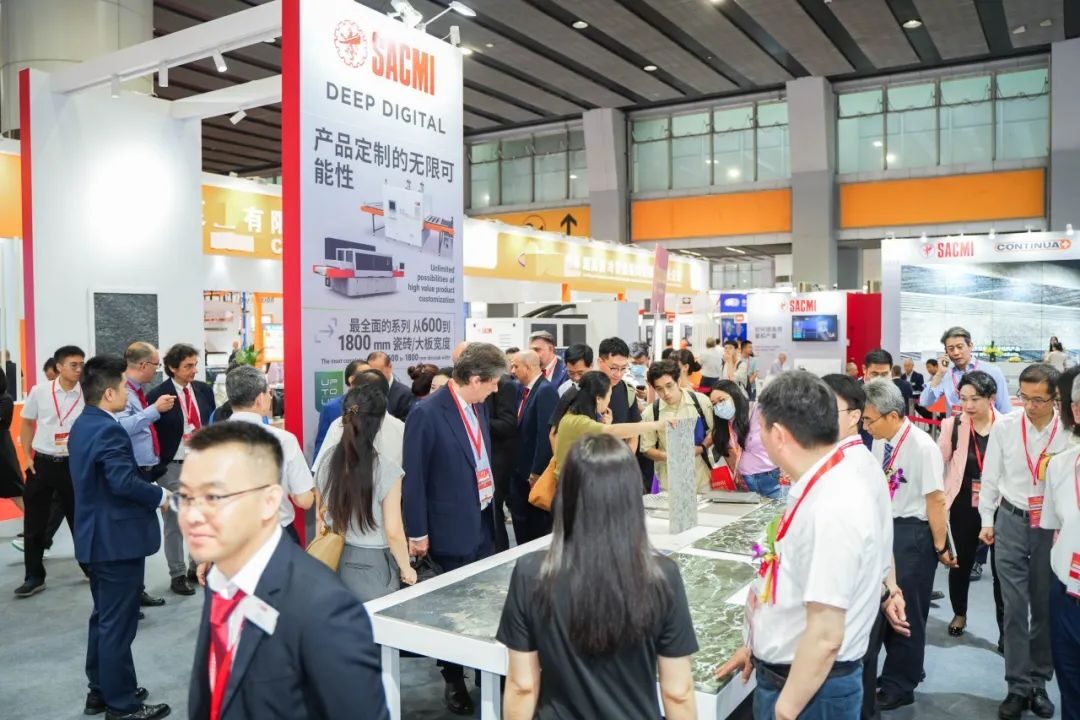

Bangladesh’s ceramic industry has evolved from modest import substitution into a thriving manufacturing hub. More than 70 factories now produce tableware, tiles, sanitary ware, and ceramic bricks that meet global standards. The domestic market is worth Tk 8,000 crore annually, while exports to over 50 countries bring in nearly Tk 500 crore. In the past decade, production capacity and investment have surged 150%, fuelled by rising demand, sharper design, and steady technological upgrades. With cumulative investment topping Tk 18,000 crore and nearly 500,000 jobs created, ceramics have become a cornerstone of the nation’s industrial growth. Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025 Amid this momentum, Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025 showcased strength and ambition. Organised by the Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BCMEA), the fourth edition ran from November 27–30 at the International Convention City Bashundhara, Dhaka. The international exhibition brought together manufacturers, exporters, machinery and raw material suppliers, technology providers, and industry stakeholders. It drew strong local and international participation, hosting 300 exhibitors from more than 25 countries, including Bangladesh, China, India, Italy, Spain, Turkey, UAE, USA, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam. Registrations topped 28,000, with visitors spanning architects, engineers, dealers, buyers, researchers, students, and officials. How the Expo Unfolded The BCMEA announced the much‑anticipated 2025 edition of the Ceramic Expo at a press conference on November 23 at the Dhaka Reporters Unity. BCMEA President Moynul Islam and Fair Organising Committee Chairman Irfan Uddin outlined key features—500 international delegates, three seminars, a job fair, B2B and B2C meetings, live demonstrations, spot orders, raffle draws, and new product launches. The briefing was attended by Senior Vice Presidents Md Mamunur Rashid FCMA and Abdul Hakim (Sumon), Vice President Rasheed Mymunul Islam, and Director Mohd Ziaul Hoque Zico. Syed Ali Abdullah Jami, director (sales & marketing) of Sheltech Ceramics Ltd., the principal sponsor of this year’s expo, joined the press meet alongside top officials of the three platinum sponsors: Didarul Alam Khan, head of marketing at DBL Ceramics Ltd.; Md Ashraful Haque, general manager (sales) at Akij Ceramics Ltd.; and Shahajada Yasir Arafat Shuvo, manager (brand) of Meghna Ceramic Industries Ltd. On November 27, Commerce Adviser Sk Bashir Uddin inaugurated the fair as the chief guest at a ceremony presided over by the BCMEA president. Partners SL Category Partner Name 1 Hospitality Partner Radisson Blu Water Garden Dhaka Regency 2 Accommodation Partner Amari Dhaka Best Western Plus Runway Crowne Plaza Grace 21 Smart Hotel Holiday Inn Intercontinental Hotel Lake Castle Platinum Grand Platinum Residence Renaissance Dhaka Westin Dhaka Chuti Resort 3 Gift Partner Hotel Lake Castle Grace 21 Best Western Plus Maya Platinum Grand Platinum Residence Dhaka Regency Hotel & Resort Ltd. Holiday Inn Dhaka Chuti Resort 4 International Event Partner Unifair Exhibition Service Co., Ltd. S.A.L.A. srl (ACIMAC) Messe Muenchen India Pvt. Ltd. 5 Knowledge Partner Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) Ceramic ISC 6 Strategic Partner Foshan Uniceramics Expo 7 Food Partner Platinum Grand 8 Official Magazine Partner Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine Asian Ceramics 9 Support Partner Export Promotion Bureau ASEAN Ceramics (Vietnam) TECNA KERAMIKA Ceramics CHINA 10 Media Partner The Business Standard Channel i Banglanews24.com Ceramic Focus Magazine Ceramic India Samakal 11 Young Engagement Partner JCI Bangladesh 12 Technology Partner Betafore 13 Wardrobe Partner FIERO 14 Connectivity Partner Amber IT Ltd. Days Full of Activities Every day of this year’s Ceramic Expo Bangladesh offered something new and innovative for visitors and industry professionals. Fresh B2B and B2C meetings unfolded across the venue, while seminars and discussions addressed pressing issues critical to resolving long‑standing challenges. After the inauguration of the expo, Commerce Adviser Sk Bashir Uddin, BCMEA President and Italian Ambassador to Bangladesh Antonio Alessandro along with top industry leaders toured the pavilions of the Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025. ACIMAC’s Project Manager Antonella Tantillo and Commercial Director of SACMI Imola S.C. Fabio Ferrari also visited the stalls. SEMINAR ONE The first seminar on “Energy Efficiency Strategies for Industry in Bangladesh: Challenges and Opportunities”, Engr. Toufiq Rahman, keynote speaker and assistant director of the Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority (SREDA), reported national progress toward a 20% reduction in energy intensity by 2030, with 15% already achieved. Md Mamunur Rashid FCMA, senior vice president of BCMEA and additional managing director of X Ceramics Ltd; SM Monirul Islam, deputy CEO and CFO of IDCOL; and Md Imam Uddin Sheikh, general manager (production & marketing) of Petrobangla, shared their thoughts. Additional insights came from Tanvir Ebne Bashar, unit head of IDCOL, on flexible financing; Matheendra De Zoysa, COO of Omera LPG, on emissions concerns; and Babor Hossain, consultant of Khadim Ceramics. SEMINAR TWO The second seminar, held on the third day of the expo on “Global Market Strategies: Challenges and Opportunities for Ceramic Products”, featured keynote speaker Dr. Aditi Shams, associate professor of International Business at the University of Dhaka, who delivered a data‑driven analysis. Dr. Mohammad Monirul Islam, associate professor at the University of Dhaka; Dr. Amir Ahmed, associate professor and head of Real Estate at Daffodil International University; M. Mamunur Rashid, CEO of Artisan Ceramics Ltd; and Baby Rani Karmakar, director general of the Export Promotion Bureau, also spoke at the event. SEMINAR THREE On the third day of the expo, the most important seminar, “Skills Development for Sustainable Growth in the Ceramics Industry”, chaired by BCMEA President Moynul Islam, also vice chairman of Monno Ceramic Industries Ltd, brought together policymakers, development partners, and industry experts. Hari Pada Das, TVET institutional strengthening expert; Mina Masud Uzzaman, member for coordination and assessment and joint secretary of the National Skills Development Authority (NSDA); ANM Tanjel Ahsan, programme officer at the ILO; Dr. Nazneen Kawshar Chowdhury, executive chairman