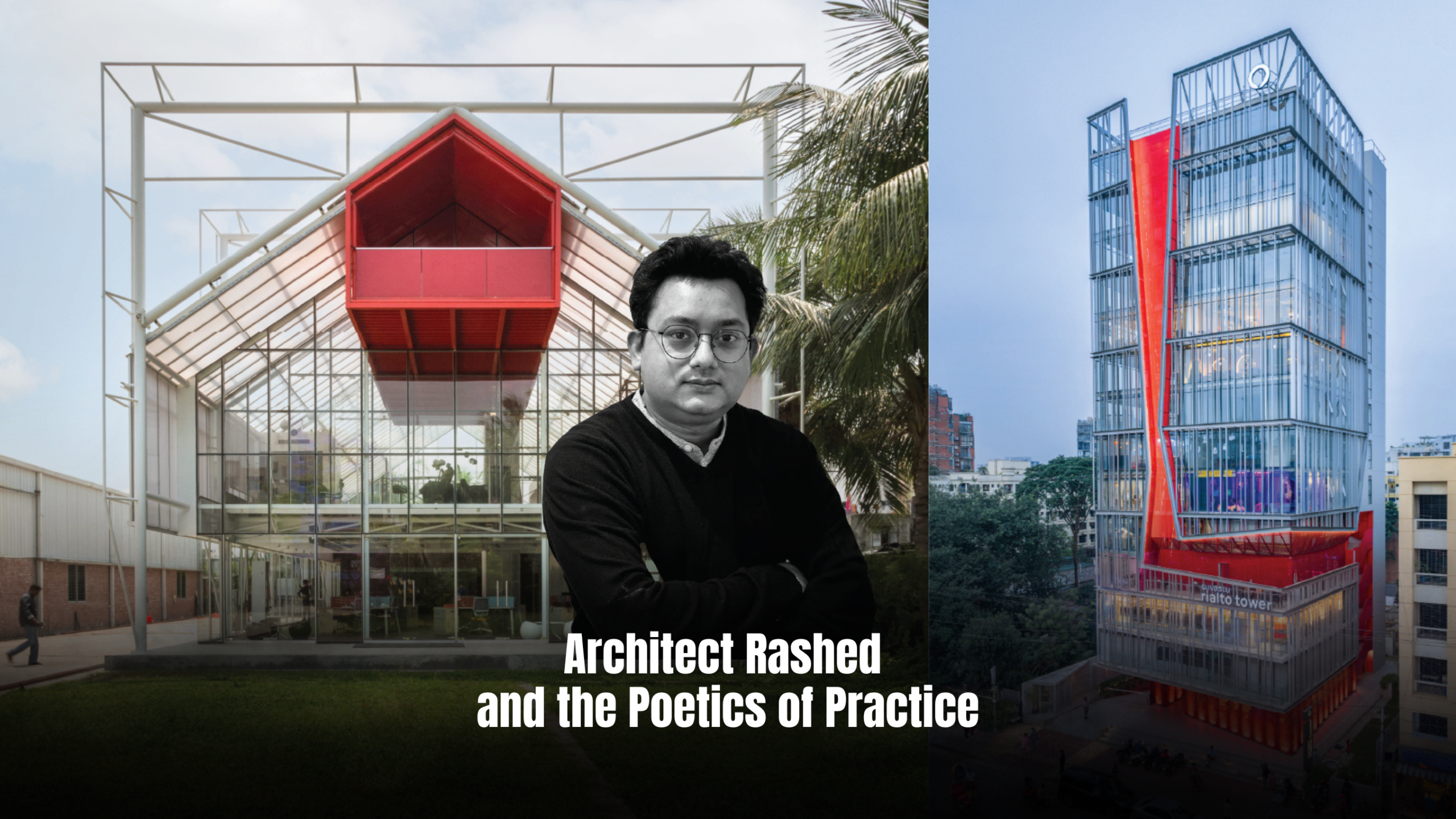

Architecture as a profession starts with untold responsibilities, especially from the day an architect realizes their observation about the surrounding necessities. The story of Architect Rafiq Azam starts somewhere there when the young and enthusiastic artist started his architectural school at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET). Uncertain about coping with architecture, his subconscious mind always wandered towards art school. Being born and brought up in the old town and surrounded by its culture, the young Rafiq developed a lateral mindset. The results of his learning reflect on his work even after 30 years of practice as a Principal Architect with his team, Shatotto architecture for green living.

From the fond memories of childhood and presently looking back to the missing pieces built the urge to refurbish the old Dhaka with a better story. But it all started with a sudden step on the realization of responsibility that he felt to hold the memories of his family, his mother, and their childhood ambiance, back when he was a third-year student struggling to survive architecture school.

After the demise of his father, they wanted to rebuild their house. His mother and her affectional emptiness of giving away her memories with her husband and adapting to a new built environment made him courageous enough to start his first design project, their residence in Lalbagh, Dhaka. The only requirement from his mother was a garden and an “uthan” (courtyard), like the one they had in their old house, where she could walk around and re-live her nostalgia.

The first of its kind, he designed a courtyard on the second floor of a building, gifting his mother the patch of green to cherish. Almost after 30 years, he did similar for the people of Rasulbagh, a small community in Lalbagh, Old Dhaka. He designed a communal park collaborating with the Dhaka South City Corporation, that is more like a courtyard gifted to the built community. According to Rafiq Azam, architecture is not just drawing and construction but more about a merging point of nostalgia and new memories. His inspiration for sticking to architecture, lastly, was to create for the mother, the soil, and the country. As he says, “I learned architecture from my mother.”

But this journey was not easy and short. The dedicated practice and research over the last 30 years, the showcase of persistence in public domains, developed trust in people. This reliance helped him influence a struggling community like Rasulbagh to revive and celebrate life. His vast experience allowed him to execute his ideas in a way that was widely accepted and even celebrated by society.

‘Architecture’s main focus should be to improve human life, working with the environment and its habitat. It should not only be limited to accommodating the luxury of elites but that of the public as well. That is how a kinship develops. ‘Urban spaces need to improve in the name of development, not just mega infrastructures; otherwise, the quality of human life will not be enhanced. And I have always been on a mission to bring a positive change,’ expressed Rafiq Azam.

Rafiq Azam’s practice has always somewhat had its roots in Old Dhaka. Earlier in his career, the wandering mind wondered about the high-thorny boundary walls of the city. He questioned the level of mistrust and hatred that people built over time. From the culture of the old town, the houses had “mer” (plinth) for people to sit and mingle, at times with mud coolers filled with water to offer the passers-by. Dhaka was a city of love and respect; it was about bonding and mingling.

The answer to this subconscious dystopia was to break the boundary walls down and oppose the convention. The practice of using glass boundaries to dissolve the visual barriers between the dwellers started. “The words ‘Kancher Deyal’ from the name of Zahir Raihan drama have inspired me to think about how a boundary can be made fragile and transparent. Hence, I started implementing them in the apartment buildings by adding plantations and benches for the passers-by. I took it as an experimental process to observe the interaction of the society,” he explained.

In 1998, Rafiq did his first solo art and architecture exhibition in New York. “People and critics appreciated my arts- a few even bought. However, for architecture, I mainly received praise for my ability to draw to international standards. The architecture was not something extraordinary, but rather the approach was very American. While I was coming back, I wrote in my diary, ‘I am coming back with hope and frustration. I realized the need to learn about my own country and how to incorporate that into modern architecture. Much of my foreign learning had to be unlearnt, which was tough. I felt myself to be intellectually corrupted,” recalled Rafiq Azam.

With this thoughtful shift of learning and unlearning, his urban and modern architecture went through an evolution. The gathered knowledge about Bangladesh, its geographical and climatic contexts, history, and culture started influencing his architecture. He showed his clients how to reminisce their childhood, just as he did with himself while designing his residence. His western drawings started getting a layer of Bengaliness, influences of poetry and literature. The rooms were no more spaces with four walls but rather got a concept. ‘Goshsha Ghor’ (a space to release anger), ‘Bristy Ghor’ (a space to enjoy rain), ‘Swimming Pond’ with ‘Ghatla’ (rural ponds with shorelines), Jongla’ (sprawl of shrubs and bushes), all these conceptually structured his architecture in better ways.

A lot of pivotal points shaped his journey. Rafiq had learned a great deal from Glen Murcutt, who spoke more about nature, history, heritage, and its association with human life. “His advice was to touch the earth lightly. Architecture is a part of nature, and the alliance between two should always be maintained,” he added.

Reflections of his learnings are observed in his translation of imagination into spaces. He connected the dots without the interference of foreign architectural languages, yet remained contemporary. Creativity can be approached in multiple ways, be it by resembling the force of nature by creating a void on the concrete and letting trees grow, or by hanging balconies to celebrate the lightness of the structural system against the wind. He brought brick and exposed concrete together to show how beautiful the coexistence of materials can be. One step at a time, small practices became his language of design.

“Architecture has been like playing a game where I incorporate harmony and rhythm from music, thoughtfulness from the philosophy, the art of directing spaces from the film, and many more areas. As much as learning aesthetics are needed, the socio-economical and semiological perspective is also needed. Learning about human psychology as we design spaces for them is very necessary,” he discussed. Rafiq Azam has many national and international awards, but his best achievement is the work he is presently doing to uplift the life of small communities like Rasulbagh and many more.

Before intervening in the Rasulbagh site, the condition of the playground was not suitable for children to play. There were no facilities for the elderly to walk or socialize. The area was surrounded by boundary walls, resulting in no public access. These walls were used as backdrops for temporary shops. Due to a lack of public orientation, the place was used for illicit activities. There was no proper drainage system resulting in waterlogging even in light rain. This problem made the area a breeding ground for mosquitoes and other insects. An open space that might have been a celebration for the community turned out as a curse.

Currently, the park is a beautiful space for celebrating life. The team has designed the area to provide solutions to all the problems. The area is no longer surrounded by walls. A park without walls is a courageous decision to make in a context like Old Dhaka. It is now a proper playground for children, a mingling space for the adults, and a breathing space for the elderly, accommodating all facilities. There are aqua trenches underneath the walkways to collect rainwater and filter it for reuse by the community. There are taps within the field where people can collect water, trying to bring back the “Kol Par” (tap facility) culture of the old town. There is a gym, a small library, and a mosque, all these together in a revamped existing building.

The Shatotto team was announced as the Regional Finalists of the first stage for the UIA 2030 Award for this particular project. The International Union of Architects (UIA), in partnership with UNHABITAT, is presenting this award. The award is honoring the work of architects contributing to the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and New Urban Agenda through built projects that portrays design quality and alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Rafiq Azam concluded, ‘taken from my favorite poet’s words “what you are seeking is seeking you”, my architectural journey has been similar. The work I do has to have a positive impact on human life, be it my mother or the whole city dwellers. The general practice should be to learn how to improve lives, which starts in the schools. The conversations in education should be more oriented towards nature and humans because only after learning these two is when we can learn architecture.’

Authored by Rehnuma Tasnim Sheefa