15th Issue

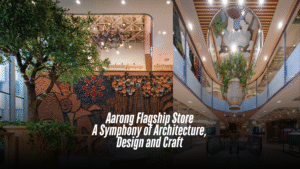

Aarong Flagship Store A Symphony of Architecture, Design and Craft

Aarong, the flagship brand of BRAC, has long been a beacon of Bangladeshi craft and heritage. Since its founding in 1978, it has evolved from a humble platform supporting rural artisans into one of the most iconic lifestyle retailers in the country. At every stage of its journey, Aarong has remained dedicated to preserving traditional crafts while embracing innovation in design and retail. This commitment culminates in its latest and most ambitious endeavor: the Aarong Flagship Store in Dhanmondi. This isn’t just a new store; it’s a monumental celebration of Bangladeshi craftsmanship, culture, and creativity. With its grand opening, the Aarong Flagship Store has become the world’s largest craft store. Yet beyond the scale, it is the thoughtfulness of the design, the intricacy of the artistry, and the profound connection to Bangladesh’s heritage that make it truly remarkable. Here, architecture becomes a canvas, interiors breathe with narrative, and every art installation stands as a tribute to the nation’s soul. Weaving a Legacy in Concrete At the heart of Dhanmondi, where tradition meets the rhythm of urban life, stands a building that does more than offer products—it tells a story. The Aarong Flagship Outlet, designed by the visionary team at Synthesis Architects, is not merely a retail space—it is a woven fabric of heritage, memory, and movement. The design draws its soul from an age-old practice: weaving. For generations, Bangladeshi artisans have mastered the loom, interlacing threads into forms that embody both beauty and utility. This fundamental craft became the architectural metaphor—fluid, connected, and timeless. A singular, sweeping ribbon—symbolic of woven fabric—emerges from the ground, bends, flows, and re-emerges, wrapping the building in a gesture that is both gentle and bold. This ribbon, meticulously cast in handcrafted concrete, intertwines tradition with contemporary expression. It shields and shelters, filters light and air, and gracefully performs the roles of both skin and soul. Designing for Aarong, a brand synonymous with preserving and promoting Bangladeshi craftsmanship, was an exercise in alignment. It was about giving architectural form to a cultural mission. The interior was choreographed as an experience. Color, texture, and flow were orchestrated to tell stories of rural hands, tribal patterns, and generational skill. The internal movement—voids, escalators, panoramic lifts—echoes the interlacing of threads on a loom. The building doesn’t simply house craft; it embodies it. There were challenges—limited plot size, urban code restrictions, and the complex layering of customer experience. But like the imperfections in a handwoven textile, these constraints added to the character. The architects embraced a rare construction process involving custom shuttering techniques that fused handcrafted care with structural innovation. It was, in many ways, architecture as craft—thoughtful, tactile, and deeply human. The Aarong Flagship Outlet is more than a commercial destination—it is a living artifact. A building where the spirit of Bangladesh rises through poured concrete, where ribbons of history and modernity interlace, and where the vision of Synthesis Architects comes alive in every curve, corner, and corridor. Narratives in Space: Designing Aarong’s Interior Stepping inside Aarong’s Dhanmondi flagship store is like entering a carefully curated journey through the textures, colors, and stories of Bangladesh. The interior design—an inspired collaboration between DWm4 Intrends Ltd, KNMR Ltd – Quirk & Associates JV, and Aarong’s in-house team—transforms the space into something far more than a retail outlet. It becomes a living, breathing storybook. From the outset, Aarong’s internal creative team played a vital role in shaping the vision. With deep roots in the brand’s philosophy and a nuanced understanding of its audience, they ensured the design remained authentically rooted in Bangladeshi heritage while pushing the boundaries of modern retail aesthetics. Guided by a philosophy rooted in transparency, movement, and nature, the space invites exploration. A rich interplay of materials, tones, and layers creates a rhythmic flow throughout the store. The tactile warmth of crafted surfaces, the strategic use of natural light, and the organic integration of greenery collectively form an ambiance that is both calming and dynamic. Each area reveals a distinct narrative, woven through thoughtful transitions that guide visitors from one crafted world to another. Every detail reflects a broader intention: to connect the threads of past and present, tradition and innovation, artisans and their audience. The space becomes part of the product’s story, amplifying its meaning and value. Executed with precision and artistry by the expert team at Charuta Limited, the interior fit-out brings this collective vision to life. At the heart of this journey was the dedicated team of architects and designers from Aarong, whose cultural insight and creative vision shaped an environment that celebrates both legacy and innovation . Art Installations: Where Stories and Spaces Intertwine Beyond architecture and interiors, the Aarong Flagship Store stands out for its large-scale art installations—transforming it from a retail space into a cultural landmark. Each piece, created by a blend of independent artists and Aarong’s in-house team, captures a different facet of Bangladeshi life and heritage. The Great Arena: A Monumental Nakshi Kantha Designed by Samiul Alam Himel in collaboration with Aarong’s in-house team, this towering four-story installation reimagines the storytelling tradition of Nakshi Kantha in architectural form. Traditionally stitched by rural women to document everyday life, these narrative quilts are here translated into flowing sculptural lines and vivid, layered colors. Titled “MohaArongo: The Great Arena,” the piece stretches 44 feet high and 10 feet wide, handcrafted over six months by 250 artisans from rural Bangladesh. The work is not only monumental in scale but also in meaning. Created from repurposed fabrics, salvaged beads, and discarded ornaments, it embodies a philosophy of renewal and resilience. The piece weaves a narrative journey through rural life, folklore, urban aspirations, and cosmic imagination—stitched in intricate Nakshi Kantha techniques drawn from Aarong’s archives and reinterpreted across various fabrics. Orange threads guide the eye through this swirling story, culminating in motifs like peacocks, trees of life, and village fairs, each carrying hidden stories within their forms. Rising through the central atrium, the installation invites viewers to look upward and

Read More

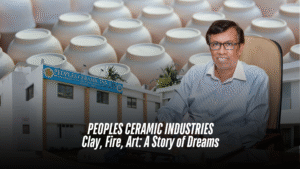

PEOPLES CERAMIC INDUSTRIES Clay, Fire, Art: A Story of Dreams

As the morning sun gently illuminates glass windows and casts playful shadows on the floor, a new day’s story unfolds. Beyond the city’s hustle and bustle, skilled hands at Peoples Ceramic Industries Limited (PCI) work tirelessly to craft each perfect piece—an extraordinary fusion of clay, fire, and creativity. Today, Bangladesh’s ceramic industry has evolved far beyond home décor into a globally recognised brand. At the forefront of this transformation is PCI. Established in 1962—originally known and registered as Pakistan Ceramic Industries Ltd.—the company has grown over 63 years into one of the nation’s oldest and most respected ceramic manufacturers. Its reputation for high-quality porcelain tableware, sustainable technology, and a robust international presence speaks for itself. In this edition of Ceramic Bangladesh, we sat down with Lutfur Rahman, the Managing Director of Peoples Ceramic Industries Ltd. A visionary in his own right, Lutfur has both preserved and expanded his father’s legacy, positioning PCI as a key player in Bangladesh’s industrial evolution. A Legacy Built on Vision and Integrity Lutfur Rahman began the interview by proudly showing a photograph of his father, Ansar Uddin Ahmed—the mastermind behind Peoples Ceramic. A civil engineer who graduated from Ahsanullah Engineering College (now BUET) in 1947, Ansar Uddin was driven by an enduring desire to serve his country—not through bureaucracy but by creating something truly meaningful. After a brief stint in the government sector, he pursued his entrepreneurial dreams. In the early 1950s, he founded United Engineers, securing a first-class license from the government. His firm was responsible for several prominent constructions that still stand today, including the Ceramic Institute in Tejgaon, Dhaka Polytechnic Institute, and Chittagong Medical College and Hospital. It was during his frequent visits to the Ceramic Institute that the idea for a ceramic factory was born. Reflecting on his father’s journey, Lutfur shared, “The relationship between children and their parents has always been special. I grew up watching my father work relentlessly, with my mother by his side supporting every step. His singular desire was to create a new industry and leave behind porcelain tableware as a legacy to improve the quality of life for our people. To realize this dream, he embarked on a long, challenging journey filled with obstacles. He always said, ‘To achieve something, one has to give up something, and there is no shortcut to building a solid foundation.’” The Birth of Peoples Ceramic In 1962, Peoples Ceramic Industries Ltd. was established with a clear and powerful vision—to provide affordable porcelain tableware for ordinary people. At a time when ceramic products were considered a luxury, Mr. Ahmed aimed to bring dignity and elegance to everyday dining. The company chose to manufacture European-style tableware, targeting both local tastes and future export opportunities. By 1982, PCI had successfully entered the international market, with its porcelain products welcomed in Holland and the United Kingdom. Located in the Tongi Industrial Area—a prominent industrial zone in Gazipur, just 20 kilometers from Dhaka—PCI started with basic housewares, tea cups, and saucers designed primarily for restaurant use. Over time, the product line expanded to include institutional ranges catering to hotels, restaurants, and the broader hospitality sector. Reflecting on the company’s humble beginnings, Lutfur recalled, “Peoples Ceramic was established in 1962, with the technical support of Sone Ceramic, Japan. At that time, Japanese engineers stayed in Dhaka to supervise the installation and production process. In the early days, our factory ran on furnace oil, and our products gained popularity right from the start.” Mr. Ansar Uddin Ahmed, who served as managing director of both Peoples Ceramic Industries and Standard Ceramic Industries Ltd., passed away on August 17, 2005. He also served as the first President of the BCMEA from 1992 to 2002, playing a vital role in revolutionising the export of local ceramics. “Tajma Ceramics, established in 1959, was the pioneer in manufacturing earthenware. However, PCI was the first to introduce porcelain production in Bangladesh,” Lutfur explained. According to him, PCI was formally inaugurated by then Industries Minister Dewan Basit and the Japanese Ambassador, with commercial production beginning on June 23, 1966. Overcoming Challenges and Embracing Innovation Marketing large-scale production in the early years posed a significant challenge. To overcome this, Mr. Ahmed ventured into the Pakistani market, successfully competing against two established factories. PCI’s hard-grade porcelain quickly won acceptance, carving out its niche within the subcontinental market. The company has consistently invested in state-of-the-art technology, global raw material sourcing, and upgraded machinery to guarantee quality and cost-effectiveness. This forward-thinking approach has enabled PCI to stay ahead of industry trends for decades. In 2009, the company introduced decal printing—initially using basic logos—and by 2012 had established a fully automated decal printing facility, expanding its design capabilities and reinforcing its brand identity. Aesthetic Diversity: Designs That Tell a Story Today, PCI offers a diverse range of tableware, neatly categorized into housewares, hotelware, and giftware. The company produces approximately 13 million pieces of porcelain tableware annually and employs nearly 712 people. These milestones stand as a tribute to its commitment to quality and innovation. The Road Ahead: Legacy and Vision Under Lutfur Rahman’s leadership, PCI continues to honor his father’s legacy with dedication and innovation. The company has adopted sustainable production practices and is actively exploring new export markets. As Lutfur puts it, “We still hold on to the principles my father set—quality, integrity, and making ceramics accessible for all. Our goal is not only to serve our customers but also to contribute to the country’s economic and industrial growth.” Looking to the future, PCI is exploring renewable energy integration, digital production processes, and expanding its footprint into emerging markets in Asia and Africa. As Bangladesh’s ceramic industry gains global prestige, Peoples Ceramic Industries Ltd. remains at its heart—a symbol of dreams forged in clay and fire, shaped by vision, and driven by a commitment to excellence. Maximizing Waste Utilization in Ceramic Production PCI is also a leader in sustainable practices. “We actively reclaim ceramic scraps at various stages of production—including the green (unfired), bisque

Read More

Celebrating 5 Years of Success of the Sponsors and Patrons Recognition

Shaping Bangladesh was one of the most prestigious events of Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine, organized by BCMEA (Bangladesh Ceramic Manufacturers and Exporters Association). The event gathered many renowned and well-known architects, engineers, industry leaders, and industry personnel from different sectors under one roof. It was a different way of introducing the new ways of rebuilding and reshaping Bangladesh with many unique and extraordinary ideas and thinking of brilliant minds and visionary individuals of the country. Without the support of the sponsors, the event would never have happened in reality. It was the encouragement, support, and dedication of the valuable sponsors who have come forward to make this event successful and create a new buzz in the town. On that note, special thanks to all the sponsors and partners of the event for making a special and notable contribution to the event and playing their part crucially. Valued Sponsors of Shaping Bangladesh Special recognition and deepest gratitude to the valued sponsors and partners for providing their invaluable support. Their generous contribution has played a significant role in making this event possible and helping BCMEA bring all the valuable communities together to promote a meaningful experience. The valued sponsors of Shaping Bangladesh were: • Platinum Sponsor: Akij Ceramics Limited • Powered by Sponsors: Meghna Ceramic Industries Limited. and X Ceramics Limited • Associated Sponsors: Sheltech Ceramics Limited, DBL Ceramics Limited, Mir Ceramic Limited Event Partners: • Gift Partner: RAK Ceramics (BD,) Ltd. • Media Partner: The Business Standard • Hospitality Partner: Dhaka Regency and Chuti Resort • Wardrobe Partner: Fiero • Other Supporting Partners: 01. BHL Ceramic Co. Ltd., 02. Mirpur Ceramic Works Ltd., 03. Ali Ceramic Ind. Ltd., 04. Adroit Swimming Ltd., 05. Nupami BD Ltd., 06. Amber Board Mills Ltd., 07. Lonon BD BCMEA and Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine are extremely grateful and honored by their presence and collaboration for the event, and they also look forward to continuing these valuable relationships in the future by working together. Top 5 Contributors in 5 years journey of Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine Shaping Bangladesh was not only an event to gather the brilliant minds, but it was also a remarkable celebration for the 5-year successful journey of Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine. BCMEA and Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine expressed their heartfelt gratitude to the constant supporters of the publication. Here are the top 5 contributors of the Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine in last 5 years who have helped to sustain the publication and allowed the magazine to grow, evolve, and continue delivering quality content to the readers, and showcase unique and extraordinary stories through the lenses of writers and photographers. Moreover, the continuous and unwavering belief in the publication was the cornerstone of this event’s success. The partnership has made the event more meaningful. BCMEA and Ceramic Bangladesh Magazine are truly honored to have all the sponsors, partners, and contributors by their side and look forward to continuing this journey together by building more impactful and significant years ahead.

Read More

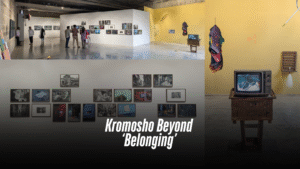

Kromosho Beyond ‘Belonging’

In the mid-2000s, a young- Munem Wasif began exploring the hidden corridors of Old Dhaka alongside his trusty, timeworn companion, Zenit—a mechanical relic from the Soviet era. This journey eventually culminated in his 2012 photographic masterpiece Belonging, a work that revolutionized visual storytelling in Bangladesh’s art scene. Much like the dark, ever-flowing waters of the Buriganga that have witnessed Dhaka’s transformation, Wasif’s artistic journey has traversed many phases—each urging audiences to look beyond the surface. From `Seeds Shall Set Us Free’ to `Collapse’, his work continuously invites deeper reflection, all while retaining an unbreakable bond with Old Dhaka. After nearly 16 years, Munem Wasif returns to Dhaka with a solo exhibition titled `Kromosho’, now on display at Bengal Shilpalay in the capital. The show, which runs until May 31, 2025, features contributions from curatorial advisor Tanzim Wahab, project assistant Iftekhar Hassan, and architectural designer Dehsar Works, and is open to everyone. Reflecting on his previous work, Wasif explained, “I felt something was lacking when Belonging was released. It merely touched upon the surface of the people and their celebrations—I couldn’t capture the core of their daily lives, the very ‘life’ of Puran Dhaka. That realization gave birth to Kheya’l. This exhibition is a testament to my transformation over the past two decades.” The opening at Bengal Shilpalay buzzed with energy as art enthusiasts gathered to witness what promises to be one of the most memorable exhibitions in recent memory. Kromosho unfolds in three movements: it begins with Wasif’s ethereal black-and-white photographs from the Belonging era, which converse with his fresh, vibrant color works from Stereo. This juxtaposition creates a dynamic tension between past and present, memory and reality. In Kheyal, a cinematic meditation captures the pulsing rhythm of Old Dhaka, while the installations Shamanno and Paper Negative blend documentation with imagination, challenging our perceptions of what is real versus what is remembered. Critically, Old Dhaka may seem like a ticking time bomb—overcrowded, decaying, and a bitter relic of collective neglect. Yet, Wasif’s work reveals the hidden vitality amid this chaos, unearthing a poetry rarely seen by the casual observer. Kromosho does more than display images of a place; it captures its very essence. The exhibition serves as a mirror, prompting us to consider what we preserve and what we forsake in our relentless march toward modernity. In an age of rapid urbanization and cultural amnesia, Wasif’s work stands as both an archive and an elegy—an enduring reminder that some stories transcend what can be captured by cameras or words. To fully appreciate its depth, one must experience it both in person and with an open, reflective heart. As visitors wander through the gallery, they are invited not only to observe but also to introspect. In this way, Kromosho transcends the role of a mere art exhibition—it becomes a conversation, a homecoming, and ultimately, a call to bear witness. Written by Shahbaz Nahian

Read More

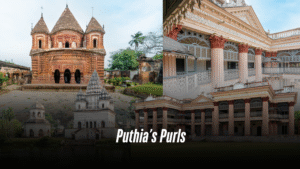

Puthia’s Purls

Nestled in northern Bangladesh in the heart of Rajshahi, the Puthia Rajbari (Palace) Complex stands as a vivid reminder of the region’s storied past. This captivating ensemble of temples and palaces—set against a backdrop of tranquil water bodies and lush greenery—offers visitors a rare glimpse into the majesty of Bengal’s bygone eras Puthia’s rise to prominence dates back to the late 16th century, evolving by the 18th century into a bastion of wealth and influence. Originally part of the Laskarpur Pargana and named after Laskar Khan Nilamber—the brother of the first zamindar, who earned the title of Raja from Mughal Emperor Jahangir—the estate underwent a significant division in 1744. This partition split the zamindari into four co-shares, with the Panch Ani (five annas) and Char Ani (four annas) shares emerging as particularly influential. The Panch Ani estate, skillfully managed by Maharani Sarat Sundari and Maharani Hemanta Kumari, became celebrated for its efficient administration and enthusiastic patronage of the arts. In 1895, Maharani Hemanta Kumari Devi commissioned the construction of the two-storied Puthia Rajbari—an architectural marvel dedicated to her mother-in-law, Maharani Sarat Sundari Devi. A fine example of Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture, the palace harmoniously blends European neoclassical ideals with indigenous Bengali design. Strategically located along the Rajshahi–Natore highway (approximately 30 km east of Rajshahi town and 1 km to its south), the palace is surrounded by protective ditches and sprawls over 4.31 acres. It is organized into four distinct courts: the Kachhari (office) courtyard, the Mandir Angan or Gobindabari (temple court), the Andar Mahal (private quarters), and the residence of Maharani Hemanta Kumari Devi. Today, the palace also functions as a museum, offering insights into the rich tapestry of Puthia’s history. Under British colonial rule, the Puthia family continued to play a pivotal role in Bengal’s governance. Eager to integrate local elites into their administrative framework, the colonial authorities relied on influential zamindars such as the Puthia royals. This collaboration enhanced their economic wealth and social standing while cementing Puthia’s reputation as an architectural and cultural beacon during the 19th century—a remarkable melding of Mughal elegance with European influences that produced a unique heritage. The palace rooms are arranged around several courts, all of which are single-storeyed except for the Kachari Angan. This section features Palladian porticos with four semi-Corinthian columns on both the western and eastern ends—one leading to the Kachari Angan and the other to the Temple (Gobindabari) courts. The porticos and central section include arcaded loggias on the first floor, while a wooden staircase on the east side ascends to three varied rooms (two of which once served as treasuries) on one side and four rooms with verandahs on the other. The northern block is double-storeyed, with a wide hall measuring 21.95 m x 7.16 m, a verandah with side balconies, and six additional rooms upstairs. In the Andar Mahal, the western section comprises two rooms and several bathrooms, while the eastern section houses a one-storeyed residence of Rani Hemanta Kumari. This residence includes a porch, a central reception hall with nine rooms, extended arch-adorned verandahs, and a roof supported by iron and wooden beams. Overall, the palace primarily served as the administrative and residential hub of the Puthia estate. The complex is also home to several iconic temples that epitomize its architectural grandeur: Bhubaneshwar Shiva Temple (1823): Constructed by Rani Bhubonmoyee Devi, this temple is the largest Shiva temple in Bangladesh. Built in the Pancha Ratna (five-spired) style, it enchants visitors with intricate stone carvings and houses a massive black basalt Shiva Linga—the largest of its kind in the country. Govinda Temple: Erected in the mid-19th century by the queen of Puthia and dedicated to Lord Krishna, this temple is famed for its exquisite terracotta ornamentation. Its five imposing spires, detailed with depictions of divine figures, epic battles, and mythological narratives, showcase the fervor and artistic talent of the region. Jagannath Temple: In a striking departure from conventional designs, this two-storied octagonal temple—dedicated to Lord Jagannath—features four pillars crowned with domes. Its unconventional shape highlights the infusion of European neoclassical elements into traditional local design. Chauchala Chhota Govinda Mandir: Dating to the late 18th or early 19th century, this temple adheres to the Char Chala style, characterized by its distinct four-cornered roof. Its terracotta façade vividly narrates rich tales from Hindu mythology, including cosmic battles between gods and demons. Bara Anhik Mandir: Representing an intriguing fusion of styles, this temple combines a central two-chala structure with two flanking four-chala wings—a rare architectural combination scarcely seen elsewhere in Bangladesh. Choto Shiv Mandir: Tucked behind the Rajbari, this humble yet finely crafted temple exemplifies the refined skills of Bengal’s artisans and provides a serene retreat for those seeking a private space for reflection. As Bengal’s social and political landscapes evolved under British influence, complexes like Puthia became more than centers of worship—they grew into symbols of local identity. The sacred grounds of the Puthia Temple Complex evoke an era when devotion, artistic brilliance, and effective governance merged to create a legacy that continues to inspire awe. Even amid challenges such as the Bangladesh Liberation War and other periods of political upheaval, dedicated preservation efforts by local authorities and heritage organizations have maintained the complex’s original splendor. In safeguarding its stone and clay, they preserve not merely a collection of monuments but a living cultural heritage that speaks volumes about the spirit of Bengal. Exploring Puthia’s legacy invites further discovery—from delving into the nuanced artistic details of terracotta carvings to understanding how colonial and indigenous influences converged to shape regional identity. This complex remains a beacon for anyone passionate about history, art, and the enduring human endeavor to immortalize culture through architecture. Written by Shahbaz Nahian

Read More

Indian Ceramics Asia

Announces New Dates for 2026 Edition: To Be Held from January 28–30, 2026 in Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India Indian Ceramics Asia, India’s only B2B trade fair for the ceramics and brick industry, has announced the dates for its landmark 20th edition. The upcoming show will take place from January 28–30, 2026, in Gandhinagar, Gujarat. Organised by Messe Muenchen India and Unifair Exhibition Services, the 2026 edition is strategically scheduled earlier in the year to better align with the industry’s annual planning and investment cycles. The new dates are expected to deliver enhanced value for exhibitors and visitors alike—unlocking fresh business opportunities, accelerating decision-making, and setting the tone for innovation-led growth across the industry. The announcement follows the successful completion of the 19th edition, held from March 5–7, 2025, at the same venue. This edition attracted over 250 brands and more than 8,000 trade professionals from 32 countries, marking a vibrant convergence of ideas, technology, and global best practices. The 2025 edition stood out for its focus on energy innovation, logistics optimization, and global competitiveness. Exhibitors like SACMI, KEDA, Sibelco, Systems Ceramics, and Modena showcased advanced machinery and raw materials aimed at making ceramic manufacturing more cost-effective and sustainable. The Live Demo Zone and Ceramics Career Connect initiatives offered real-time learning and talent engagement, further enriching the visitor experience. International pavilions from Italy and Germany brought in automation-centric solutions and sustainable practices, strengthening cross-border collaboration. As the industry continues to navigate challenges around energy, supply chains, and global demand, Indian Ceramics Asia remains the sector’s most trusted platform for innovation, networking, and growth. Join us from January 28–30, 2026, in Gandhinagar—and be part of the ceramics industry’s defining event in South Asia. For more details, visit www.indian-ceramics.com

Read More

Bangladesh Investment Summit 2025 A New Dawn for Economic Growth?

Bangladesh now stands at a critical crossroads. As the country prepares to transition from a least-developed nation (LDC) to a middle-income economy in 2026, it grapples with significant hurdles. Despite years of economic resilience, enduring issues—such as import dependency, skill shortages, stagnant private investment, and declining foreign direct investment (FDI)—continue to slow progress. In this challenging environment, the Bangladesh Investment Summit 2025 emerged as a pivotal event, unveiling initial investment proposals worth Tk 31 billion (3100 crore) and igniting cautious optimism among policymakers and investors. Convergence of Promise and Challenges Organized by the Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA), the four-day Dhaka summit, held from April 7 to April 10, 2025, brought together over 550 investors and business representatives from more than 50 countries. Inaugurated by Chief Advisor Dr. Muhammad Yunus, the summit sought to reimagine Bangladesh’s global investment identity even as it faced structural challenges. Ultimately, the success of these initiatives will hinge on whether early commitments evolve into sustained and tangible investments. For years, Bangladesh’s investment landscape has remained largely stagnant. Overall investments have hovered between 24–28 percent of GDP, with private investment stuck at 22–24 percent and FDI persistently below 1.0 percent. Recent declines in private investment in FY2023 and FY2024, along with a continuous drop in FDI since FY2018, have been attributed to bureaucratic hurdles, policy unpredictability, and macroeconomic instability—particularly in managing exchange rates. Yet, amid these challenges, the summit has sparked a renewed sense of hope. Global Multinationals Betting on Bangladesh Three major international companies announced expansion plans during the summit: Inditex (Spain): The retail giant behind Zara reaffirmed Bangladesh’s role as a key sourcing hub and hinted at increased procurement. Lafarge Holcim: The cement leader discussed plans to broaden operations and explore carbon capture initiatives. Handa Industries (China): The company committed $150 million to develop textile, dyeing, and garment units in designated economic zones. In addition, Dubai-based DP World expressed interest in investing in Chattogram’s new Mooring Container Terminal. Celebrating Local Champions Local enterprises also received significant recognition at the event. Four Bangladeshi firms were honored for their contributions: bKash (Excellence in Investment): The trailb lazing mobile financial services provider backed by IFC, Ant Group, and SoftBank. Fabric Lagbe (Innovation Award): A digital marketplace that empowers traditional weavers. Walton (ESG Award): A leading local electronics manufacturer exporting to over 40 countries. Square Pharmaceuticals (Investment Excellence): A company that has grown from modest beginnings in Pabna to a globally recognized pharmaceutical powerhouse. These success stories underscore that, despite systemic challenges, Bangladeshi enterprises can thrive on the international stage. Global Investors Show Confidence There is growing international faith in Bangladesh’s revised approach to investment. Foreign investors have commended the interim government for taking proactive measures to attract FDI—a marked departure from previous administrations. A delegation of 60 investors from the U.S., South Korea, China, Japan, India, Australia, and the Netherlands toured key hubs such as the Korean Export Processing Zone (KEPZ) in Chattogram and the Japani Export Processing Zone (JEPZ) in Narayanganj, exploring opportunities in textiles, IT, and manufacturing. KEPZ: A Model Investment Hub Operated by South Korea’s Youngone Corporation, KEPZ has become a shining example of Bangladesh’s readiness for FDI. Investors were impressed by its well-established infrastructure, efficient licensing procedures, and worker-friendly amenities—including a hospital, a textile institute, a 40MW solar project, and an effluent treatment plant. With $700 million already invested, KEPZ now hosts 48 factories and employs 30,000 workers, 75 percent of whom are women. Forging Sustainable Partnerships The summit also facilitated key agreements. Notably, BIDA, the Commerce Ministry, ILO, and UNDP issued a joint declaration to promote sustainable and inclusive growth through targeted trade reforms. Additionally, UK Trade Envoy Baroness Rosie Winterton highlighted long-term opportunities in healthcare and education, paving the way for enduring global partnerships. Navigating the Road Ahead: Can Bangladesh Overcome Its Investment Slump? Despite the summit’s positive momentum, Bangladesh’s investment climate continues to face obstacles: High bank interest rates that deter private borrowing. Policy inconsistencies under the interim government create uncertainty. Weak FDI performance compared to regional competitors like Vietnam and India. Analysts stress that without significant structural reforms—streamlining bureaucracy, ensuring policy stability, and stabilizing the macroeconomy—Bangladesh may struggle to sustain the anticipated investment surge. Execution is Key The Bangladesh Investment Summit 2025 has successfully rebranded the country as an emerging investment destination. With multinationals such as Inditex, Lafarge Holcim, and Handa Industries pledging expansion and local leaders like bKash and Walton proving their global competitiveness, there is considerable cause for optimism. However, the real challenge now lies in execution. Only if Bangladesh addresses its business environment hurdles, refines regulatory frameworks, and maintains macroeconomic stability can this new momentum herald a transformative economic chapter. For now, the world watches closely—will Bangladesh seize this moment, or will these early promises fade away? Only time will tell. Written by Sajibur Rahman

Read More

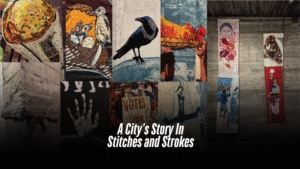

A City’s Story In Stitches and Strokes

Dhaka’s rapid urbanization is impossible to ignore. This city of relentless energy and transformation is a place where tradition and modernity collide amidst its bustling streets and ever-changing skyline. As the economic heart of Bangladesh, it draws thousands seeking better opportunities. But this comes at a cost: overcrowding, strained resources, and a growing disconnect between the old and the new. Against this backdrop, ShohorNama Dhaka Episode II sought to explore the city’s complexities through art. Launched in early 2024, the project brought together visual artists, architects, artisans, and students from the University of Dhaka’s Faculty of Fine Art to create a tapestry of urban narratives. And the exhibition of this project took place from February 15 to 25 at the level 4 under construction space of the capital’s Bengal Shilpalay. The exhibition was inaugurated by H.E. Marie Masdupuy, Ambassador of France to Bangladesh, on February 15, 2025. Titled after the project name, the multidisciplinary exhibition wove together the threads of urban life, resilience, and creativity. Presented by the Bengal Arts Programme in collaboration with the Britto Arts Trust, ShohorNama II was a visual love letter to Dhaka, its people, and their stories. From large appliqué tents to wood-cut prints, installations, and performance art, it was a celebration of Dhaka’s artistic topography. At its core, ShohorNama was about storytelling. One of the standout features is the Pakghor Project, a community kitchen born out of necessity during the devastating floods of 2024 in the Khulna region. Pakghor provided warm meals to 500 villagers for a week. But it became more than just a kitchen—it became a space for shared stories, resilience, and hope. The Dorjikhana Project takes a different approach, focusing on textiles and their cultural significance. Through appliqué and embroidery, artists explore the connection between traditional practices and the modern garment industry. The project also draws inspiration from Bangladesh’s fading circus traditions. Resulting in a stunning collection of textile art that speaks to both the past and the present. Another striking element of ShohorNama is its use of tents. Historically, tents have symbolized temporary shelter for nomadic communities, and in this exhibition, they represent the fluidity of migration—whether due to natural disasters, economic hardship, or political unrest. The Big Tent installation captured this impermanence, reflecting the challenges faced by marginalized communities. The exhibition also highlighted the collaborative spirit of the project. Workshops with the University of Dhaka’s Department of Printmaking and Department of Craft allowed students to contribute to large-scale works, such as woodcut prints and appliqué pieces. These workshops not only honed technical skills but also fostered a sense of shared purpose, blending individual creativity into a cohesive vision. The exhibition was a feast for the senses! As Dhaka continues to evolve, exhibitions like “ShohorNama Dhaka Episode II” remind us of the importance of preserving our stories and traditions. Through art, we can find common ground, build resilience, and imagine a better future. Written by: Shahbaz Nahian Photo: Bengal Art Foundation | Courtesy

Read More

Where Nature Literature and Architecture Converge

Every person envisions a path uniquely their own. For Mesbah-ul-Kabir, the visionary force behind Kabir and Associates, that path was rooted in literature—especially Bangla literature, which continues to capture his heart. Picture a building as if it were a poem: its floors serve as verses, its design the underlying rhythm, and within the interplay of these elements unfolds the poetic vision of its creator. Though destiny steered him away from writing verses, it set him on the course of designing ones conceived in concrete, glass, and steel. When asked about his design philosophy, Mesbah replied, “I don’t follow a singular style. Instead, I draw inspiration from nature—the master designer. Nature effortlessly embraces the path of least resistance, creating a harmonious, albeit imperfect, balance. Unlike manmade objects that often adhere to strict forms, every new project demands its own innovative treatment. I learn and evolve with each undertaking.” This commitment to constant reinvention has defined his career and led him to craft iconic structures like the Sena Kalyan Bhaban—which redefined Dhaka’s skyline—and Mirpur’s National Stadium, among many others. In Bangladesh, Mesbah-ul-Kabir’s name is synonymous with architectural excellence. Yet, he always reminds fellow architects that the learning process never truly ends. He laments that only a handful of his peers still embrace the hands-on method of constructing scale models with simple, analog tools—a practice increasingly eclipsed by computerization. “I purposely avoid relying on computer software,” he explains firmly. “By drawing perspective sketches and building scale models by hand, I retain total control over my creative process.” He recalls how, during his studies at BUET, a chance encounter with the legendary Dr. Fazlur Rahman Khan left a lasting impression: “When I envision a building, I feel its weight as if it were part of me.” Such experiences underscore the importance of imagination—a quality he fears is slowly being overshadowed by digital methods. Reflecting on his earlier days, Mesbah recounts a time when understanding a client’s desires led to rough sketches, known as ‘functions,’ followed by detailed perspective drawings imbued with vanishing points, horizons, and everyday elements like trees or vehicles. These handcrafted visualizations offered a glimpse of a project’s future long before modern tools like AutoCAD existed. Even the laborious process of constructing scale models gave him a satisfaction akin to a poet reveling in a freshly composed verse. Today, a visit to the Kabir & Associates office in Dhanmondi reveals a gallery of these cherished drawings and models—a living history of a lifetime dedicated to craftsmanship. Despite the encroachment of digital design, Mesbah holds a hopeful vision that emerging architects will rediscover the profound joy of traditional creation. For him, architecture is boundless. “Some choose this profession out of necessity; I embraced it with passion,” he reflects. His academic journey spanned literature, history, physics, mathematics, philosophy, and even music during his time at BUET’s Department of Architecture. Even within the scientific rigors of his field, literature remained a wellspring of inspiration—a force that uplifted him from isolation and exposed him to a vast ocean of creativity. While celebrated for his monumental public works and commercial edifices, some of Mesbah-ul-Kabir’s most treasured designs are the modest homes of the 1970s and 1980s in neighborhoods like Gulshan, Banani, and Baridhara. These projects, though simple, exuded warmth and personality—whether through rooftop gardens, multi-story green spaces, or even rooftop swimming pools—offering a style of luxury living that contrasts sharply with today’s prevalent, box-like apartment blocks. He fondly recalls a whimsical project for the former vice president of Summit Group—a full-glass house in Savar Cantonment. Enchanted by a monsoon season enlivened with blooming red lotuses, the client once declared, “I want to present this glass house to my wife.” When pressed about privacy, particularly in intimate areas and restrooms, he quipped about using curtains, noting humorously that the secluded setting made privacy a minor concern. Notably, Mesbah introduced the curtain wall system on the Sena Kalyan Bhaban for the first time in Bangladesh—a testament to his innovative spirit, which is also reflected in designs for national stadiums and even the previous Gulshan Club. Mosques occupy an especially sacred space in Mesbah’s repertoire. Having designed and refined over a hundred mosques, he approaches these projects not as commercial ventures but as acts of ‘khidmah’ (service)—an opportunity to contribute selflessly to the community. “Designing mosques is both a duty and a passion, a way to express gratitude for the gifts of life and our own abilities,” he explains. His first mosque, the Azad Mosque—more widely known as Gulshan Central Mosque—was a landmark project that spanned nearly 18 bigha and featured striking geometric designs with circles and triangles. Drawing on decades of experience, Mesbah elaborates on the cultural significance of religious structures. While domes, arches, and minarets have transcended their practical origins—minarets, once essential for calling worshippers to prayer, now serve largely symbolic roles—they remain vital in linking a building’s design to its cultural and spiritual roots. Architecture, in his view, acts as the binding force that enshrines ideological meanings across diverse cultures, even as building materials and techniques evolve. The evolution of mosque design is an ever-unfolding process. Take the Baitul Aman Mosque on Dhanmondi Road 7, which began as a humble prayer space enclosed by bamboo fencing. Over time, enhancements like the addition of balconies, multiple floors, and modernized interiors—with steel window frames, marble finishes, and wooden elements—have transformed it into a communal haven that harmonizes with its upscale neighborhood and the nearby natural charm of Dhanmondi lake. For Mesbah, each mosque should feel inseparable from its surroundings, a tribute to both its community and its environment. Today, Bangladesh’s architectural scene is thriving—high-rise, elegant, and meticulously streamlined structures now dot the landscape. Young architects enjoy the profession far more than in earlier times, even as government projects, though commendable, sometimes lack the incentives necessary to retain top talent. Yet, despite these challenges, he remains confident that given the right opportunities and motivations, these architects will

Read More

Exhibitors of Ceramic Expo Bangladesh 2025

The 4th edition of Ceramic Expo 2025 is going to be held from November 27 to November 30, 2025, at the International Convention City Bashundhara (ICCB) in Dhaka. The event is one of the most prestigious and premier B2B events focused on the ceramic finished products of the local manufacturers and foreign companies with new machinery, raw materials and innovation. There will be 40+ local manufacturers of ceramic products, such as tiles, tableware, sanitaryware, ceramic bricks, pottery etc. and 75+ foreign exhibitors from more than 25+ countries along with 300+ brands and 500+ delegates. The local and foreign exhibitors both will enhance the quality and standard of the Ceramic Expo 2025 by showcasing their latest products and innovation. The expo is not only promoting the growth and development of the business but also expanding the opportunities to going global for the business expansion. Written by Preety Dey

Read More

FOSHAN DONGHAI TECHNOLOGY CO. LTD. Ceramic Body Decoration Technology | Digital Powder-Jet System

Digital Powder-Jet System | Precise Alignment, Full-Body Texture Donghai Technology’s Digital Powder-Jet System is an advanced feeding technology that utilizes intelligent control systems and multi-channel coordination to impart vibrant patterns and textures. Each channel carries different colored powder, precisely applying the desired designs through digital nozzles. This advanced technology not only enhances production efficiency but also customizes to meet the diverse clients’ need, showcasing a full-body effect from the surface to the bottom. Digital Powder-Jet System’s Advantages: (1) Superior compatibility, seamless Integration with all types of press, (2) Feeding Channel from 6-12 (optional). (3) High-speed feeding, up to 10m/min, achieving both production and efficiency. (4) High precision and accuracy, with positioning accuracy controlled within 2-3mm. Ceramic Surface Decoration Technics | Dry Applicator Dry Applicator | Digital Grit, Premium Finish Donghai Technology’s Dry Applicator is a specialized equipment used for the surface decoration of ceramic tiles. It mainly through the technology of glue and dry grit. By evenly spreading various dry granular materials on the surface of the tiles, it significantly enhances the decorative effect of the tiles. Its advanced technics technology, bringing brand-new possibilities to the surface decoration of ceramic tiles. Dry Applicator’s Advantages: (1) Perfect combination with ink-jet technology, tile surface with rich effect of concave & convex. (2) Italian imported belt, precise control of grit, feeding uniformity. (3) With heating device, remove the humidity of grit during recycling. (4) With automatic recycling system, grit can be reused. (5) Provide professional process technical support, design effect can be realizable.

Read More

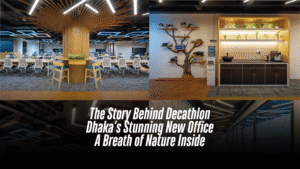

The Story Behind Decathlon Dhaka’s Stunning New Office

In the center of Dhaka’s relentless urban sprawl, Decathlon’s new liaison office has carved out an unexpected oasis. Designed by Studio one zero, the two-floor, 20,000-square-foot workspace is a lively yet calming blend of nature, sport, and smart design — a triumph achieved under the intense pressure of a compressed timeline. One floor of the office is devoted to a sprawling seminar and multi-purpose event space, while the other flourishes as a vibrant open-plan workspace. Together, they embody Decathlon’s global brand ethos: movement, accessibility, and connection to the environment. From the first step inside, the design immediately surprises. Natural light pours in from every angle, with open workstations, informal seating zones, and collaborative spaces stretching toward the glass walls. But what truly distinguishes the space is its deliberate, sensitive incorporation of natural elements into an otherwise urban setting — a concept that chief architect Jafor Hoq and Partner Architect Humaira Binte Hannan at Studio One Zero were determined to bring alive. Challenge Against Time “The biggest challenge for us,” says Jafor Hoq, “was the design decision against time. From the initial concept to execution, we had a very short period. And it wasn’t just about filling a space — Decathlon wanted something meaningful, experiential, and true to their brand spirit.” Working under intense deadlines and changes meant that decisions on materials, layouts, and designs had to be made rapidly but thoughtfully. “We had no time for second-guessing. Every material, every design move had to be purposeful and achievable within the timeframe,” Hoq recalls. Instead of battling the constraint, Studio one zero leaned into it, focusing on a few strong ideas and executing them meticulously. Bringing Nature Indoors — A Different Way While biophilic design is no longer a novelty, Studio one zero’s approach for Decathlon’s office is refreshingly nuanced. Instead of merely placing potted plants in corners, nature was embedded into the structure itself. The most striking feature — the tree-inspired columns — originated from a need to solve a technical problem with artistic flair. Existing structural columns, often seen as obstacles in open-plan offices, were transformed into vertical wooden sculptures. “These columns are not just cladded structures,” Hoq explains. “We intentionally gave them the form of large tree trunks, expanding outward at the top, creating a canopy-like feeling. Under these ‘trees,’ we placed high seating zones, making them natural gathering points where people can sit, stand, and connect. It’s about reinterpreting indoor nature — not just bringing in greenery but evoking the experience of being under a tree.” Materiality: Warmth in an Industrial Frame The material palette reflects a thoughtful balance between modernity and warmth. Light oak wood cladding runs through the flooring of common pathways and wraps around key architectural elements, providing a sense of warmth and continuity. “The idea was to humanize the space,” says Hoq. “We were working with an exposed ceiling — which gives that industrial look — but we didn’t want it to feel cold or impersonal. Using wood, texture and incorporating green , was the answer.” Meanwhile, the furniture choices favored light-colored wood and clean lines to complement the architecture without overwhelming it. Lush green walls filled with planters further softened the industrial base, offering breathing spaces that look and feel alive. Even the lighting played into the natural narrative. Angular, dynamic geometric light fixtures, seemingly random yet deliberate, mimic dappled sunlight filtering through tree canopies, casting a playful rhythm of light and shadow across the workspace. Functionality at the Core Of course, Decathlon’s office needed to be more than beautiful; it needed to work. Beyond the seminar space and open workstations, Studio One Zero integrated a variety of amenities including a gym, prayer rooms, a sick room, and a restaurant-style café. The café, with its relaxed seating and natural materials, encourages casual interaction — a deliberate attempt to break down formalities and foster an easy, collaborative culture. Flooring materials shift subtly from wood to textured carpet tiles to indicate different zones without physical barriers, preserving the openness. Every design choice speaks to movement, flexibility, openness and wellness — values at the heart of both Decathlon and Studio one zero’s architectural philosophy. A Space That Moves People In the end, Decathlon’s Dhaka office is more than a workplace. It’s a living, breathing environment, where the boundaries between indoor and outdoor, formal and informal, structured and free-flowing, are beautifully blurred. Studio One Zero’s bold vision — executed under a limited timeframe — has resulted in a space that isn’t just seen; it’s felt. A place where employees can experience the spirit of sport, the calm of nature, and the excitement of innovation, every single day. “We didn’t just design an office,” Jafor Hoq smiles. “We designed an experience.” Written By Fatima Nujhat Quaderi Photo: Truphoto Studio

Read More

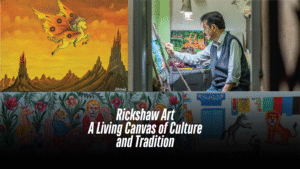

Rickshaw Art A Living Canvas of Culture and Tradition

Dhaka’s wheel The rickshaw is the quintessential three-wheeler of Dhaka. If one were to encapsulate the spirit of the city with a single vehicle, it would undoubtedly be the rickshaw. Even in an era dominated by modern transport and ride-hailing services, the rickshaw remains a beloved tradition. Riding in a rickshaw, one can experience a serene immersion in nature—a reflective calm—despite the bustling chaos of Dhaka outside. More than a means of transport, rickshaws are mobile masterpieces. Handcrafted by skilled artisans, they feature oil paintings adorned with vibrant floral patterns, birds, animals, movie stars, and scenes from folk tales, effectively transforming the streets into a roving gallery. On December 6, 2023, UNESCO recognized Bangladesh’s rickshaw art as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity—a distinction that has gripped global attention and sparked renewed domestic interest. Galleries across the country are now hosting exhibitions to celebrate this unique cultural tradition. History throughout The three-wheeled rickshaw has been a part of Bangladeshi life since the 1940s. By the late ‘40s, decorative elements such as movie star portraits and intricate floral designs began to appear, heralding the birth of what is now known as rickshaw art. Originating in Rajshahi and Dhaka, this art form evolved with each district contributing its own unique stylistic influences. Artist Syed Ahmad Hossain has been a devoted practitioner of rickshaw art since 1969. A self-taught talent, his works have not only graced exhibitions around the world but also served as a visual chronicle of his era. During the Liberation War, for instance, he vividly captured scenes of conflict on rickshaws, transforming them into moving narratives of historical events. In 1975, political unrest led to fears of a ban on rickshaw painting, prompting many artists—including Syed—to shift their focus to signboard painting. Concurrently, rising religious sensitivities rendered the portrayal of human faces and film scenes controversial, ushering in a new era where artists gravitated toward universally acceptable subjects such as trees, animals, and nature. Gradually, human faces were replaced with symbolic imagery that communicated profound stories without uttering a single word. Syed recalls a time when cheap, mass-produced prints of rickshaw art flooded the market, selling for merely 60–70 taka. Although these replicas lacked the detail and artistry of the originals, their affordability made them popular. This oversaturation, however, contributed to a devaluation of authentic rickshaw art. During Pohela Boishakh, rickshaw art transforms from vehicle decoration into a marketable commodity. Artisans create posters, canvas prints, postcards, and figurines that feature iconic rickshaw designs; these items are cherished as souvenirs, home décor, or thoughtful gifts. Such initiatives underscore the collective effort required to preserve and celebrate this cultural tradition. Wheels got heavier! Today, the art of hand-painted rickshaws teeters on the brink of extinction. The rise of motorized rickshaws—lacking the space for detailed artwork—and the advent of digital printing have contributed to its decline. With only a few traditional rickshaw artists remaining, there is growing concern that this vibrant form of pop art may be lost. Innovative artists are finding new expressions for rickshaw art beyond the vehicles themselves. Syed, for example, has successfully translated this living art onto handcrafted items like hurricane lamps, trunks, and portraits. Meanwhile, contemporary artists like Hanif Pappu express worry over the waning interest among the younger generation, who are often discouraged from pursuing this craft due to its limited financial rewards. Photo: UNESCO, DBF, Courtesy Written by Fariha Hossain

Read More